10 regole per studenti e insegnanti da John Cage

Ogni tanto controllo se il sito tedesco in cui è in corso l’esecuzione di Organ2/ASLSP di John Cage, dilatata all’incredibile durata di 639 (seicentotrentanove) anni, esiste ancora e la risposta finora è sì.

Per saperne di più su questa epica esecuzione iniziata nel 2001 e destinata a terminare nel 2640, vi rimando

Infine, qui potete ascoltare l’epico cambio di nota del 2006 a 8:36 in questa clip audio. L’ultimo è stato nel 2013 e il prossimo è atteso per il 5 settembre 2020.

Questo è l’organo utilizzato per l’esecuzione.

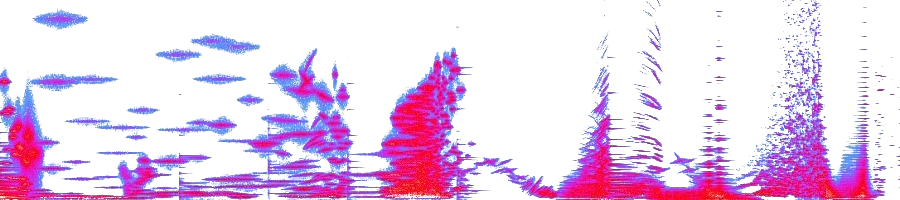

C’è anche questa versione di Matthew Reid che è abbastanza interessante. Reid ha eseguito il brano filtrando il microfono con un equalizzatore regolato in modo da rinforzare le frequenze di risonanza della stanza. Di conseguenza si è prodotto un feedback.

La registrazione è stata poi passata in Autotune che ha intonato tutti i feedback, sia il bordone del secondo movimento che i vari suoni del terzo. In un certo senso è una versione elettroacustica del brano.

La popolarità di John Cage ormai ha raggiunto livelli impensabili. Ecco 4’33” eseguito da Infestation, una brutal death metal band. I commenti su You Tube sono pochi, ma favorevoli e anch’io trovo sia un’esecuzione ben fatta.

Il 2012 è il centenario della nascita di John Cage e il ventennio dalla morte (Los Angeles, 5 settembre 1912 – New York, 12 agosto 1992). Ovviamente le celebrazioni sono molte. Presumibilmente, quasi tutta la sua opera sarà eseguita quest’anno e qualcuno si accorge anche di qualche problema.

Peter Urpeth, nel suo blog silentmoviemusic, ha fatto notare che, probabilmente, uno dei più famosi e caratteristici brani di Cage, Radio Music, composto nel 1956, diventerà ineseguibile a partire dal 2017 e forse la stessa fine farà Imaginary Landscape 4 (e qualche altro brano basato sulla radio). Questi pezzi, infatti, sono scritti per un certo numero di esecutori (da 1 a 8 il primo, 12 il secondo), ognuno munito di una radio. La partitura di Radio Music riporta una lista di frequenze su cui gli apparecchi devono essere sintonizzati nel corso del brano. La lista è indipendente dal luogo e dall’orario dell’esecuzione, per cui ne esce un insieme indeterminato di suoni. Occasionalmente, su qualche frequenza non c’è alcuna trasmissione e quindi si sente il silenzio della radio, fatto di rumore di statica con qualche disturbo casuale.

Il fatto che mette in pericolo Radio Music è lo spegnimento del segnale analogico previsto per il 2017, segnando il passaggio definitivo alle trasmissioni digitali. Le conseguenze sono due:

La partitura, dunque, appare obsoleta rispetto a un recente salto tecnologico. Non è la prima volta che questo accade nella storia della musica. Penso, per esempio, al passaggio dall’arco barocco a quello moderno, o dal clavicembalo al pianoforte, tuttavia, in questi casi, la sostanza del discorso musicale, cioè la successione di altezze, rimaneva e consentiva una nuova interpretazione.

Ci sono, poi, altri casi legati a un salto tecnologico. Nella musica elettronica il passaggio dall’analogico al digitale ha messo in crisi varie partiture. Tuttavia con il digitale si può emulare il 99% di quello che si faceva in analogico, sia pure con qualche differenza, ma che, in fondo, non è più grande di quella provocata dall’abbandono del clavicembalo in favore del pianoforte.

In questo caso, invece, è proprio la sostanza del brano a cambiare e se il suo significato, che consiste nella sovrapposizione casuale di varie sorgenti radiofoniche, può essere riprodotto, vengono a mancare sia una serie di rumori (statica, disturbi, ricerca della sintonia), che quella commistione di trasmissioni normali e di servizio (sistemi di trasporto, emergenze, CB) che un tempo lavoravano con lo stesso medium, ma che ora sono definitivamente separati.

Non credo, comunque, che Cage si sarebbe preoccupato più di tanto della fine di Radio Music, anzi l’avrebbe accolta come un altro passo verso il silenzio, ma il silenzio digitale è troppo perfetto…

Nell’immagine David Tudor e John Cage (click per ingrandire), trovata via johncage.org. Vi riporto anche il bel sito JOHN CAGE unbound: a living archive, creato dalla New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, segnalato da Franz.

John Cage – In The Name of the Holocaust (1942), for prepared piano.

Like much of Cage’s early dance music (this to accompany a piece by Merce Cunningham), In the Name of the Holocaust was written for what Cage would later refer to as a ‘prepared piano’: a piano with screws, bolts, or other materials placed between certain strings to create a percussive effect.

The music features a number of new piano techniques, many of which Cage borrowed from his teacher Henry Cowell: notes held open for resonance, muted and plucked strings, and clusters played with the arm and flat of the hand. The title references World War II and comes from a pun on the Catholic liturgical phrase “In the Name of the Holy Ghost” found in James Joyce’s novel Finnegans Wake.

John Cage – In The Name of the Holocaust (1942), Margaret Leng Tan, piano

Robert Wyatt sings John Cage’s The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs for voice and piano. The piano stay closed and is used as a percussion instrument.

The song was commissioned by singer Janet Fairbank, who later became known for pioneering contemporary music. Cage chose to set a passage from page 556 of Finnegans Wake, a book he bought soon after its publication in 1939. The composition is based, according to Cage himself, on the impressions received from the passage. The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs marks the start of Cage’s interest in Joyce and is the first piece among many in which he uses the writer’s work.

The vocal line only uses three pitches, while the piano remains closed and the pianist produces sounds by hitting the lid or other parts of the instrument in a variety of ways (with his fingers, with his knuckles, etc.) Almost immediately after its composition the song became one of Cage’s most frequently performed works, and was several times performed by the celebrated duo of Cathy Berberian and Luciano Berio. Cage later composed another piece for voice and closed piano, A Flower, and a companion piece to The Wonderful Widow of Eighteen Springs, called Nowth upon Nacht, also based on Joyce’s book.

From Obscure 1 LP

John Cage, Freeman Études for solo violin (1977). A piece whose form is due to a set of misunderstanding.

In 1977 Cage was approached by Betty Freeman, who asked him to compose a set of etudes for violinist Paul Zukofsky (who would, at around the same time, also help Cage with work on the violin transcription of Cheap Imitation). Cage decided to model the work on his earlier set of etudes for piano, Études Australes. That work was a set of 32 etudes, 4 books of 8 études each, and composed using controlled chance by means of star charts and, as was usual for Cage, the I Ching. Zukofsky asked Cage for music that would be notated in a conventional manner, which he assumed Cage was returning to in Études Australes, and as precise as possible. Cage understood the request literally and proceeded to create compositions which would have so many details that it would be almost impossible to perform them.

In 1980 Cage abandoned the cycle, partly because Zukofsky attested that the pieces were unplayable. The first seventeen études were completed, though, and Books I and II (Études 1-16) were published and performed (the first performance of Books I and II was done by János Négyesy in 1984 in Turin, Italy). Violinist Irvine Arditti expressed an interest in the work and, by summer 1988, was able to perform it at an even faster tempo than indicated in the score, thus proving that the music was, in fact playable. Arditti continued to practice the études, aiming at an even faster speed, apparently misreading Cage’s indication in the score to play every measure in “as short a time-length as his virtuosity permits”, in which Cage simply meant that the duration is different for each performer. Inspired by the fact that the music was playable, Cage decided to complete the cycle, which he finally did in 1990 with the help of James Pritchett, who assisted the composer in reconstructing the method used to compose the works (which was required, because Cage himself forgot the details after 10 years of not working on the piece). The first complete performance of all Études (1-32) was given by Irvine Arditti in Zurich in June 1991. Négyesy also performed the last two books of the Etudes in the same year in Ferrara, Italy. [wikipedia]

Un video in cui David Tudor itself esegue 4’33”, registrato molto probabilmente per una TV giapponese.

La cosa più buffa è il messaggio che scorre in sovrimpressione:

You are invited to turn down the volume of your TV set, and listen to the ambient sounds present wherever this program is performed.

Non si capisce perché abbassare il volume della TV se il brano è silenzioso, come se gli eventuali suoni trasmessi dall’apparecchio non fossero degni di essere ascoltati.

Notations, la leggendaria antologia edita nel 1969 da John Cage ed Alison Knowles, contenente molti esempi di notazione grafica e ormai da anni fuori catalogo, è disponibile per il download qui. (att.ne pdf di 300+ pagine, circa 74 Mb)

Credo in Us di John Cage.

Dated: New York, July, 1942. Revised October 1942

Instrumentation: 4 performers: pianist; 2 percussionists on muted gongs, tin cans, electric buzzer and tom-toms; one performers who plays a radio or phonograph;

Duration: 12′

Premiere and performer(s): August 1, 1942 at Bennington College in Bennington, Vermont, performed with the choreography by Merce Cunningham and Jean Erdman

The work was composed in the phraseology of the dance by Cunningham and Erdman. For the first time Cage uses records or radios, incorporating music of other composers in his own works. He suggests music by Dvorak, Beethoven, Sibelius or Shostakovich. Cage describes the work as a suite with a satirical character.

Jean Erdman recalls that for the first performance a ‘tack-piano’ was used (a piano with tumbtacks inserted onto the felt of the hammers). The pianist mutes the strings at times or plays the piano body (as a percussionist).

Fontana Mix e Aria sono due composizioni di Cage del 1958-59 registrate qui in esecuzione simultanea e sovrapposta.

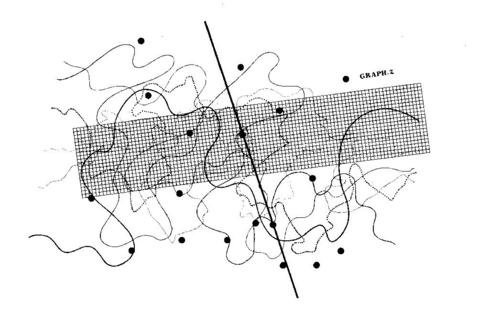

Fontana Mix è in realtà un sistema compositivo utilizzato per la prima volta nella stesura del Concerto per Piano e Orchestra (1957-58). Consiste di 10 fogli e 12 trasparenti. I fogli contengono ciascuno 6 linee curve. Dei 12 trasparenti, 10 contengono punti dispersi casualmente (7, 12, 13, 17, 18, 19, 22, 26, 29 e 30 punti), uno ha una griglia e uno ha solo una linea retta.

Piazzando i trasparenti con punti sui fogli con le curve e interpretando il tutto con l’aiuto della linea retta e della griglia, si possono ottenere indicazioni compositive.

Con questo metodo, nel 1958-59, Cage ha realizzato, presso lo studio di fonologia della RAI di Milano con l’assistenza di Marino Zuccheri, i due nastri che tradizionalmente compongono Fontana Mix.

Con lo stesso metodo, ha anche composto Water Walk Sounds of Venice, Aria, Theatre Piece e WBAI. Quest’ultimo altro non è che una serie di indicazioni liberamente combinabili per la regia del suono in brani che coinvolgono registratori, controlli di volume/tono e altoparlanti ed è spesso usato nella realizzazione di Fontana Mix.

Aria (1958) è una partitura di 20 fogli ognuno dei quali dura un massimo di 30 secondi. Il testo impiega vocali, consonanti e parole in varie lingue. La notazione consiste di linee ondulate in vari colori e 16 quadrati che rappresentano rumori vocali. I color denotano differenti stili di canto, determinati dall’esecutore.

Sempre da UbuWeb, ecco il film di Peter Greenaway, Four American Composers (1983).

Diviso in quattro parti, è dedicato a Robert Ashley, John Cage, Philip Glass e Meredith Monk.

From UbuWeb, here is the Peter Greenaway’s film Four American Composers (1983).

The composers are Robert Ashley, John Cage, Philip Glass and Meredith Monk.

UbuWeb ha messo in linea questa pagina dedicata a John Cage da cui potete scaricare vari scritti, nonché le partiture dei Song Book I e II libro per voce.

C’è anche il testo del 1966 “How to Improve the World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse)” e vari Mesostics.

1960: John Cage esegue la sua Water Walk nella popolare rubrica televisiva I’ve Got A Secret davanti ad un attonito presentatore che lo tratta come una specie di freak.

Notate come la performance (che inizia al minuto 5) sia eseguita con grande serietà, nonostante le risate del pubblico.

Più o meno lo stesso era accaduto nel 1958 a Lascia o raddoppia (da dove, peraltro, se ne era andato con in tasca un bottino di $6000).

Here’s John Cage performing Water Walk in January, 1960 on the popular TV show I’ve Got A Secret.

John Cage’s lecture.

The lecture begins with reading of Mureau, the first part of “Empty Words”, which is based on a Thoreau text. The program concludes with a lengthy question and answer session that followed Cage’s appearance at the Cabrillo Music Festival in August 1977. It is often in addressing the public’s questions that Cage’s brilliance is most memorable, and this example is no exception. Of particular interest is his description of how he uses chance operations in his creative processes.

Una lezione tenuta da John Cage nell’agosto 1977.

Inizia con una esecuzione di Mureau, una lettura basata su testi di Henry David Thoreau, che, qualche anno dopo, diventerà la prima parte di Empty Words.

Mureau (1970) è descritto come

An I-Ching determined Collage of Quotes on Music, Sound & Silences from the Diaries of D.H.Thoreau

e in effetti il titolo è la giustapposizione della prima parte della parola Music e di quella finale di Thoreau.

Prosegue, poi, con una serie di domande del pubblico e relative risposte. Di particolare interesse, in questa seconda parte, la descrizione dell’utilizzo di operazioni casuali come parte del processo creativo.

from Internet Archive

Mureau can also be downloaded from UBUWeb in a 1972 execution.

Un giusto titolo per Pasqua.

Qui abbiamo “The Perilous Night”, composto nel 1943/44 da John Cage per pianoforte preparato. Uno dei brani in cui è maggiormente evidente il carattere percussivo della preparazione del pianoforte.

John Cage – The Perilous Night (1943/44) – Benjamin Kobler prepared piano

Il giorno in cui qualcuno si laurea con una tesi su John Cage seguita e ispirata dal sottoscritto deve essere celebrato, per cui mettiamo questo post.

All’inizio del 1947 John Cage scrisse The Seasons, un Balletto in un atto pensato per la compagnia di Merce Cunningham che la portò in scena nello stesso anno con scene e costumi di Isamu Noguchi.

Il brano prende la forma di una suite in 9 movimenti: Prelude I – Winter – Prelude II – Spring – Prelude III – Summer – Prelude IV – Fall – Finale (Prelude I).

Si tratta di una composizione dolce e lirica che, come le Sonate e Interludi e lo String Quartet, si ispira, concettualmente, all’estetica indiana nella quale l’inverno è visto come uno stato di quiete, la primavera come creazione, l’estate come conservazione e l’autunno come distruzione.

È uno di quei pezzi in cui Cage tenta di “imitare il modo di procedere della natura”, altra idea tratta dalla filosofia indiana e il brano, pur nella sua complessità ritmica, ha un andamento ciclico, con la fine che equivale ad un nuovo inizio. Così anche Cage, come altri compositori, ha le sue stagioni in cui le cose nascono, crescono, mutano e si distruggono, ma qualche volta ritornano.

In realtà The Seasons esiste in due versioni. Quella per piano solo venne composta per prima e in seguito Cage la orchestrò con l’aiuto di Lou Harrison and Virgil Thomson.

Qui potete ascoltare lo stesso estratto (Prelude I e Winter) in entrambe le versioni e apprezzare le differenze di uno stesso testo affidato prima alla concentrazione monotimbrica del pianoforte in cui, proprio per questo, l’interprete deve giocare su sottili sfumature coloristiche e poi alla pluralità di suoni dell’orchestra, più ricca, ma anche meno definita dal punto di vista ritmico e armonico.

John Cage – The Seasons (1947)

solo piano version – Margaret Leng Tan, pianoforte

orchestral version – BBC Symphony Orchestra conducted by Lawrence Foster

Che Stockhausen, Xenakis, Ligeti, Boulez, Cage e molti altri del genere avessero uno spazio su MySpace non lo avrei mai detto, ma la fede dei fans è grande e accade anche questo.

La cosa è stata portata alla mia conoscenza dai colleghi bloggers di sounDesign in questo post (c’è anche una interessante proposta cageana).

Naturalmente, nello spazio dedicato a John Cage, uno dei brani ascoltabili è il solito 4’33″… (ma anche la delicatissima Music for Marcel Duchamp). Ovviamente non ho resistito e ho lanciato l’ascolto dell’infame brano silenzioso  L’ho ascoltato guardando l’indicatore del traffico di rete che mostrava kili e kili di zeri viaggiare da MySpace al mio computer.

L’ho ascoltato guardando l’indicatore del traffico di rete che mostrava kili e kili di zeri viaggiare da MySpace al mio computer.

4’33” è il pezzo di Cage più scambiato in rete, è in vendita su iTunes a $ 0.99, è stato oggetto di una causa: tonnellate di banda usate ogni giorno per trasmettere il nulla…

Se però penso agli skirillioni di bytes che viaggiano ogni ora per trasmettere idiozie, preferisco di gran lunga il nulla, che, come il vuoto quantico, è un nulla che non è vuoto.

Il vento dell’Oriente e il vento dell’Occidente si incontrano in America e producono un movimento ascensionale nell’aria; lo spazio, il silenzio, il nulla che ci sostiene…

Grande, JC…

A proposito, andate a votare, sfaticati, cabrones…

Fa un certo effetto vedere insieme due leggende della musica del ‘900: Edgar Varèse (sin.) e John Cage (centro) con il percussionista Max Neuhaus (des.) in una foto ormai sgranata pubblicata sul New York Times (September 1, 1963).

Ci sono dieci tuoni nel Wake. Ognuno è un crittogramma o una spiegazione codificata delle conseguenze tonanti e riverberanti dei principali cambiamenti tecnologici in tutta la storia umana. Quando un uomo tribale sente un tuono, dice: “Cosa ha detto quella volta?”, con la stessa spontaneità con cui diciamo “Gesundheit” (trad. “Salute”).

[Marshall McLuhan]

Ecco i tuoni (in realtà non tutti sono veri tuoni, alcuni sono battimani, colpo di tosse, sbattere di porta…), come li ha scritti James Joyce e il primo interpretato da John Cage

Bababadalgharaghtakamminarronnkonnbronntonnerronntuonnthunntrovarrhounawnskawntoohoohoordenenthurnuk

Perkodhuskurunbarggruauyagokgorlayorgromgremmitghundhurthrumathunaradidillifaititillibumullunukkunun

Klikkaklakkaklaskaklopatzklatschabattacreppycrottygraddaghsemmihsammihnouithappluddyappladdypkonpkot

Bladyughfoulmoecklenburgwhurawhorascortastrumpapornanennykocksapastippatappatupperstrippuckputtanach

Thingcrooklyexineverypasturesixdixlikencehimaroundhersthemaggerbykinkinkankanwithdownmindlookingated

Lukkedoerendunandurraskewdylooshoofermoyportertooryzooysphalnabortansporthaokansakroidverjkapakkapuk

Bothallchoractorschumminaroundgansumuminarumdrumstrumtruminahumptadumpwaultopoofoolooderamaunsturnup

Pappappapparrassannuaragheallachnatullaghmonganmacmacmacwhackfalltherdebblenonthedubblandaddydoodled

husstenhasstencaffincoffintussemtossemdamandamnacosaghcusaghhobixhatouxpeswchbechoscashlcarcarcaract

Ullhodturdenweirmudgaardgringnirurdrmolnirfenrirlukkilokkibaugimandodrrerinsurtkrinmgernrackinarockar

Da Good Morning Silicon Valley:

And I made this ringtone from John Cage’s 4’33” for calls from the office

Questo utilizzo non era previsto, ma è geniale.

C’è sul solito YouTube questo film di Dick Fontaine (regista indipendente fra i primi a usare il direct cinema), diviso in 3 parti (tot. 25 minuti ca.), in cui un giovane John Cage (giovane rispetto a come lo ricordo io; in realtà ha 50+ anni) e Rahsaan Roland Kirk (sassofonista di quel jazz sperimentale e afro, tipico dei roaring sixties) parlano del suono (a un certo punto compare anche David Tudor). Naturalmente lo fanno da punti di vista opposti, tanto opposti che a volte si compenetrano.

È anche bello rivedere le cose che faceva Roland Kirk, tipo il suonare insieme 2/3 sassofoni, oppure quei soli di flauto che diventeranno pop grazie a Ian Anderson.

Soprattutto c’è quella simpatica atmosfera anni ’60 in cui sembrava fosse possibile provare tutto. Erano appunto i tempi dei festival ONCE, in cui ogni cosa poteva essere tentata almeno una volta.

Il parlato è in inglese sottotitolato in francese, ma comunque si capisce senza sforzarsi (Cage parla piano e chiaro). Questa è la prima parte. Seguono i link.

Il periodo del pianoforte preparato inizia nel 1940 con il brano Bacchanale di Cage, composto per la danza di Syvilla Fort.

Può darsi che Cage non sia stato il primo a introdurre materiali vari nel pianoforte, ma sicuramente è il primo che lo fa consciamente e sviluppa l’idea, per cui la storia lo ricorda come l’inventore di questo ‘strumento’. In effetti, nelle sue mani, il pinoforte preparato si trasforma in un ensemble piano-percussioni con sonorità che vanno dalla marimba, a piccoli tamburi, fino al pianoforte vero e proprio, passando per i suoni metallici di campane non intonate i cui rintocchi sono dedicati non a un Dio, ma al Nulla.

Analiticamente, possiamo esaminare le preparazioni per le Sonatas & Interludes (1948), di cui vedete una immagine del risultato (click immagine per ingrandire). In base all’effetto acustico, si possono classificare in 4 categorie:

| Oggetto inserito | Effetto | Note |

|---|---|---|

| Pezzi di gomma o altro materiale smorzante | Simile allo smorzatore: il suono viene bloccato con effetto percussivo |

Il suono è più o meno smorzato in base alla distanza dell’oggetto dal punto di percussione |

| Viti o altri oggetti metallici puntuali | Creazione di un ‘nodo’ nella corda con produzione simultanea di più suoni | Il risultato dipende strettamente dalla distanza dell’oggetto dal ponte: sui punti in cui si producono armonici, questi ultimi vengono evidenziati. In punti diversi si producono suoni non armonici con sustain più breve |

| Lamelle o altri oggetti vibranti | La nota, più o meno smorzata, è accompagnata dalla vibrazione della lamella | |

| Oggetti posati sulle corde | Intensa vibrazione |

Infine, bisogna tener presente che l’inserimento di oggetti altera più o meno leggermente la tensione delle corde fra cui sono inseriti, quindi si hanno anche effetti di leggera scordatura.

In questi brani, le preparazioni non sono oggetto del caso. Cage di che esse «vanno scelte come le conchiglie su una spiaggia», cioè in modo intuitivo, senza un piano preciso.

Dal 1940 al ’52, scriverà circa 30 pezzi per questo strumento di cui è, ovviamente, il principale utilizzatore, ma che, soprattutto negli Stati Uniti, verrà usato anche da altri compositori. In Europa, invece, la cosa ha scarso seguito. Gli europei, a partire dai primi anni ’50, si dedicano a un intenso studio per allargare le possibilità acustiche del pianoforte creando suoni compositi di cluster e note singole con diverse durate e dinamiche, arrivando a risultati decisamente belli (pensiamo soprattutto a Stockhausen), quanto di difficile esecuzione, ma raramente osano toccare l’interno del piano che rimane come un feticcio freudiano nella cultura musicale europea. Vale la pena di notare, però, come l’effetto di una singola vite di Cage sia spesso paragonabile a un intero suono composito.

La giustificazione portata dal nostro per l’invenzione del pianoforte preparato è in sè stessa una provocazione tale da far saltare i nervi a qualsiasi europeo. Secondo la tradizione artistica europea, le innovazioni arrivano come risultato di una ricerca oppure come effetto collaterale di quest’ultima (vedi il saggio di Stockhausen su Scoperta e Invenzione). La spiegazione di Cage è, invece, assolutamente pratica: per la danza di Syvilla Fort serviva un gruppo di percussioni, ma, nei piccoli teatri in cui si esibiva, non c’era sufficiente spazio, per cui il pianoforte è stato trasformato in modo da produrre anche suoni percussivi.

Tornando alle Sonatas & Interludes, possiamo notare come, nonnostante il titolo, siano formalmente lontane dalla sonata classica:

È interessante ascoltare una sonata, per es. la prima, guardando la partitura (click immagine qui sotto per ingrandire). Si nota che corrispondenza suono – segno non esiste più.

Le Sonatas & Interludes, infatti, hanno effetti collaterali che vanno al di là dell’opera in sè stessa. Se ci pensate, infatti, siamo in presenza di un deciso mutamento nella funzione della partitura.

La normale partitura è una ‘partitura di risultato’. Essa informa l’interprete di ciò che il compositore vuole ottenere, non di quali azioni si debbano compiere per ottenerlo. Quest’ultima parte è compito dell’esecutore che deve capire il brano, costruirsi una diteggiatura, eccetera.

Nella partitura delle Sonatas, invece, c’è una differenza fondamentale: non sempre il risultato corrisponde a quanto è scritto. L’esecuzione di una nota, spesso, non produce quella nota, ma un suono che con quest’ultima può anche avere ben poco a che fare. Pensateci bene: l’analisi pura e semplice della partitura, senza sapere niente delle preparazioni, porterebbe su una strada completamente sbagliata. In questo caso, la partitura non è l’opera.

Si tratta, quindi, di uno dei primi esempi moderni (perché andando indietro esistono le intavolature) di ‘partitura operativa’ in cui il compositore non indica il risultato, ma le azioni da compiere. Il risultato, poi, è altra cosa.

John Cage (1912-1992) . Sonatas and Interludes (1946-48) for prepared piano

Orlando Bass, piano

Sonata 1 // 00:07 Sonata 2 // 02:21 Sonata 3 // 04:13 Sonata 4 // 06:20 Interlude 1 // 08:20 Sonata 5 // 11:10 Sonata 6 // 12:50 Sonata 7 // 15:08 Sonata 8 // 17:21 Interlude 2 // 19:21 Interlude 3 // 22:43 Sonata 9 // 25:22 Sonata 10 // 28:32 Sonata 11 // 30:46 Sonata 12 // 33:15 Interlude 4 // 36:25 Sonata 13 // 39:40 Sonata 14 // 42:40 Sonata 15 // 44:40 Sonata 16 // 46:45

Merce Cunningham (proprio lui) danza sulle Variations V di John Cage (molti anni fa,,,)

Su Archive.org sono disponibili alcune interessanti interviste, ovviamente in inglese, con: Brian Eno (1980), Astor Piazzolla (1989), Cathy Berberian (1972)

Si trovano anche le registrazioni di alcuni concerti, come questo di Cage e Tudor del 1965.

On the site Archive.org we can find some interesting interviews with Brian Eno (1980), Astor Piazzolla (1989), Cathy Berberian (1972).

There is music also. Listen to this Cage and Tudor concert (1965).

Londra, 23 settembre 2002.

Gli avvocati delle parti si fronteggiano per dirimere l’ennesimo caso di plagio. Ma questa volta l’oggetto della causa è un po’ speciale. Il musicista pop Mike Batt ha inserito in un album della sua rock band “The Planets” un brano intitolato “One minute of silence”, il cui contenuto corrisponde al titolo ed è stato accusato di plagio dal John Cage Trust (NB: gli eredi di Jonh Cage che è morto nel 1992) e dalle Edizioni Peters, editore del brano 4’33” (ovviamente 4’33” ha una partitura: è in 3 movimenti all’inizio dei quali è scritto “tacet”).

L’incontro si conclude con un accordo extra-guidiziale. Batt consegna un assegno a 6 cifre (in sterline) a Nicholas Riddle, managing director delle Edizioni Peters e aggiunge il nome di Cage come co-autore di “One minute of silence”, dichiarando “Faccio questo gesto come segno di rispetto verso John Cage” 8) . Riddle intasca l’assegno e afferma “Noi intendiamo difendere la proprietà di Mr. Cage e il concetto di brano silenzioso è una idea importante sulla quale c’è un copyright” :lol:.

Molto interessante. In effetti, Riddle ha dalla sua almeno un precedente: il quadro bianco, non dipinto, il “White Painting” di Rauschenberg è protetto e chiunque lo rifaccia può essere accusato di plagio.

D’altra parte il silent piece è, appunto, un concetto. Il contenuto del silent piece è l’insieme dei suoni che si sentono mentre il musicista non suona.

Ma se, in musica, si possono brevettare i concetti, allora è la fine. Per esempio, i cluster (accordo formato da note vicine, tipicamente 2e minori come do, do#, re, re#, mi) cominciano ad apparire timidamente in musica nel primo ‘900 (Debussy, Bartok, Ornstein, Ives), ma il primo che ne fa un uso esteso e consapevole è Henry Cowell in “The Tides of Manaunaun” (1917; non 1912 come è spesso riportato).

Di conseguenza, Cowell avrebbe potuto porre un copyright sul cluster. 3/4 della musica del ‘900 cancellata.

Schoenberg avrebbe messo un copyright sulla dodecafonia. Messiaen avrebbe potuto chiedere i diritti sui modi a trasposizione limitata, Boulez sul serialismo integrale, Debussy sulla scala esatonale e Stockhausen sull’universo in musica. Per non parlare della musica pop: causa interminabile fra Deep Purple e Led Zeppelin su chi abbia inventato l’hard rock.

Per inciso, questo è esattamente quello che sta succedendo negli USA con i brevetti sul software, che finora l’Europa è riuscita a negare.

Prendete un software per il P2P (questa prova è stata fatta con eMule). Cercate John Cage, selezionando il tipo di file = audio. Poi ordinate i risultati in base alla disponibilità di sorgenti (cioè alla quantità di utenti che l’hanno messo in condivisione).

Scoprirete che il file audio di Cage più scambiato in rete è 4’33”.

Sì! Fra i pezzi di Cage, quello più ascoltato in rete è proprio la composizione silenziosa, nella versione per piano.

Ma la gente…

Tiding up old books I found this one: Desert Plants – conversations with 23 american musicians by Walter Zimmermann, Vancouver, 1976. An old style book, clearly printed and written with IBM electric typewriter. Questions in italic and answers in monospace fonts.

Browsing I found this gag:

Walter Zimmermann to Philip Glass:

John Cage describes your work as follows: “Though the doors will always remain open for the musical expression of personal feelings, what will more and more come through is the expression of the pleasures of conviviality. And beyond that a non-intentional expressivity: a being together of sounds and people.”

How do you relate this quote to your music?

A bothered Philip Glass:

Well, I think it has more to do with his music than mine.

Riordinando i vecchi libri mi è caduto in mano questo: Desert Plants – conversations with 23 american musicians by Walter Zimmermann, Vancouver, 1976. Un libro vecchio stile scritto con una macchina elettrica IBM. Le domande stampate in corsivo e le risposte nei classici caratteri da macchina da scrivere.

Sfogliando qui e là ho trovato questa gag:

Walter Zimmermann a Philip Glass:

John Cage describes your work as follows: “Though the doors will always remain open for the musical expression of personal feelings, what will more and more come through is the expression of the pleasures of conviviality. And beyond that a non-intentional expressivity: a being together of sounds and people.”

How do you relate this quote to your music?

Philip Glass, seccato:

Well, I think it has more to do with his music than mine.

Ecco il video di una mitica esecuzione di 4'33" per orchestra. Il momento in cui il direttore si deterge il sudore fra il primo e il secondo movimento è puro humour inglese.

Problema: come valutare una esecuzione di 4'33" :-P?

Here is the video of a good execution of Cage’s 4'33", orchestral version. The director wiping off his sweat between 1st and 2nd movement is a moment of great humour.

Problem: how to evaluate a 4'33" execution :-P?

I have nothing to say

and I am saying it

and that is poetry

as I needed it

— John Cage

http://youtu.be/zY7UK-6aaNA

In realtà succede per caso, però sono molto contento di aprire questo blog parlando di John Cage.

Nella piccola chiesa di St. Burchardi, in Halberstadt (Germania), è in corso l’esecuzione di Organ2/ASLSP di Cage, iniziata nel 2001, la cui durata prevista è di 639 anni (finirà nel 2639).

In breve 🙂 la storia è questa.

La Composizione

L’ASLSP originario è un brano del 1985 per pianoforte solo: 4 pagine manoscritte, nello stile sparso e delicato dell’ultimo Cage. Il titolo è insieme una indicazione esecutiva e un riferimento al sempre presente Finnegan’s Wake:

The title is an abbreviation of ‘as slow as possible.’ It also refers to ‘Soft morning, city! Lsp!’ the first exclamations in the last paragraph of Finnegans Wake (James Joyce).

(Cage, note collegate alla partitura)

Si tratta di un lavoro in 8 sezioni, una delle quali, all’atto dell’esecuzione, deve essere omessa e sostituita con una qualsiasi altra, che, quindi, viene ad essere eseguita due volte.

La notazione è quella tipica di molti lavori di Cage, con parti non correlate fra le due mani, ma da eseguirsi simultaneamente. Le altezze sono scritte in modo preciso, mentre le durate devono essere calcolate, con una certa approssimazione, in base alla distanza fra le note. Il tempo e la dinamica sono liberi (ma quest’ultima dovrebbe essere soft). Nelle diverse esecuzioni, la durata varia fra 6 e 25 minuti.

Nel 1987, su suggerimento dell’organista Gerd Zacher, l’indicazione strumentale venne estesa all’organo e il titolo divenne Organ2/ASLSP. Chiaramente, la versione per organo è radicalmente diversa da quella per piano. Da un lato, infatti, scompare quel delicato gioco di risonanze generato da alcuni tipici manierismi cagiani, come quello degli accordi eseguiti in staccato, tranne una nota che può essere tenuta anche oltre l’estinzione e vibra per simpatia come un pedale tonale. Dall’altro, però, il cambiamento investe in modo sostanziale l’interpretazione dell’indicazione “as slow as possibile” che può essere estesa praticamente all’infinito, grazie alle note tenute. Se, con il pianoforte, tenere un accordo per 10 minuti non ha senso o, al massimo, ha un senso cagiano (l’irrompere dei suoni esterni nello spazio che si crea nella composizione), con l’organo siamo al bordone potenzialmente infinito alla La Monte Young.

In effetti, nel 1997, a Trossingen, organisti e musicologi riuniti a congresso si trovarono a dibattere, fra l’altro, dell’interpretazione di quel “as slow as possibile”, contemplando anche la tesi estrema di una composizione che trascende i limiti non solo del tempo di un concerto tradizionalmente inteso, ma del tempo stesso (il desiderio di eternità è connaturato alla specie umana). Di qui, il progetto.

Il Progetto

Il progetto è quello di una esecuzione, localizzata in Halberstadt, della durata di 639 anni. Perché Halberstadt e perché 639 anni?

Semplicemente perché la cattedrale di Halberstadt ospita il primo organo liturgico di cui si abbia notizia, il Blockwerk organ di Nikolaus Faber. Questo strumento è anche il più antico organo esistente con tastiera a 12 note organizzata secondo lo schema di quelle attuali, il che comunque non comporta una accordatura temperata. La suddetta tastiera risale, infatti, al 1361, cioè 639 anni prima del 2000, anno del secondo millennio e della presentazione del progetto.

C’è, dunque, un collegamento simbolico, un passaggio di testimone fra uno degli organi più antichi e il più popolare compositore contemporaneo (oggi, su Google, John Cage ha 26.800.000 reference, Stockhausen 3.170.000, Boulez 2.520.000, Schoenberg 5.130.000, Webern 1.520.000 e il sottoscritto meno di un migliaio. Per confronto, l’intera famiglia Bach ne ha 78.300.000).

Il luogo dell’esecuzione è la cappella sconsacrata di St. Burchardi, una delle più antiche d’Europa (ca. 1050), più volte semidistrutta e ricostruita e attualmente lasciata in stato di degrado. Si è reso, quindi, necessario un restauro. Nella stessa, inoltre, è stato anche piazzato un nuovo organo che è tuttora in via di ampliamento (nuove canne vengono installate via via che si rendono necessarie altre note).

L’esecuzione è iniziata nel 2001, il 5 Settembre, data di nascita di Cage, il cui spirito ironico si è manifestato alla cerimonia di apertura quando l’organista si è limitato ad avviare lo strumento e andarsene, in quanto la partitura inizia con una pausa la cui durata, fatti i debiti calcoli, risulta essere di un anno e mezzo.

Solo nel febbraio 2003 si sono sentite le prime note: una triade SOL#,SI, SOL# alla quale, nel 2004, si sono aggiunti due MIb in 8va, destinati a terminare il 5 Maggio di quest’anno. Il 2006 è comunque un anno ricco di eventi perché il 5 Gennaio quel che rimaneva del primo accordo era stato sostituito dal secondo: LA, DO, FA# (ovviamente i tasti vengono bloccati con dei pesi).

Per convenzione, tutti i cambiamenti vengono eseguiti il 5 di ogni mese alle 5 pm, sia per ricordare il giorno di nascita del nostro, che per facilitare la vita ai turisti.

Infine, per la modica cifra di € 1000, potete dare il vostro nome a un anno e sponsorizzare parte del progetto (anche in condivisione): una targa metallica viene piazzata sul posto con il vostro nome e una frase di vostra scelta. Gli anni fino al 2010 e anche altri nell’arco di una vita umana, sono già stati venduti. Più avanti nel tempo c’è ancora molto posto, sebbene alcuni ottimisti abbiano già acquistato il 2639.

Qualche riflessione

IMNHO (in my never humble opinion), credo che i sospetti di strumentalizzazione che nascono inevitabilmente di fronte a operazioni di questo tipo, possano essere messi da parte. Se, da un lato, è vero che la connessione con Cage può apparire forzata e gratuita (ci sono vari autori contemporanei più significativi per l’organo rispetto a lui, per es. Messiaen, e la stessa idea di composizioni che durano anni è di La Monte Young), è anche vero che nessuno ha proposto sfide visionarie come il nostro e che con questo progetto si raggiungono alcuni risultati apprezzabili:

Soprattutto quest’ultimo punto mi interessa. Perché, se a qualche mente limitata una composizione di 639 anni può sembrare solo un’idea balzana, per una che fa lavorare la propria immaginazione è una bella fonte di riflessione.

Innanzitutto, il senso musicale. Anche con durate di gran lunga inferiori a 639 anni, il senso della composizione svanisce. Come insegna la psico-acustica, quando un evento dura abbastanza da “bucare” la capacità della memoria a breve termine (inferiore al minuto), la sua connessione con il tutto si perde. In pratica, se si suona una banale progressione armonica tenendo ogni accordo per un tempo superiore al minuto, non si ha più la sensazione di una progressione, ma ogni accordo tende a diventare un mondo a sè.

Così, entrando nella chiesa di St. Burchardi non si ascolta una parte di una composizione, almeno non nel senso che diamo comunemente a queste parole. Piuttosto si entra in un ambiente che in quel momento è in quello stato. Magari il bordone è una 8va tranquilla, mentre tornando 6 mesi dopo c’è una dissonanza raccapricciante ed è bella l’idea di un ambiente sonoro che si evolve come un ambiente biologico.

Quindi, dal punto di vista sonoro, si tratta di una esperienza che, per la maggior parte della gente, è nuova, e questa è una delle funzioni dell’arte.

Veniamo adesso alla durata. 639 anni sono un sacco di tempo. In passato, simili distese temporali erano prese in considerazione solo dalle religioni (…nei secoli dei secoli…) o dagli imperi (l’imperatore dei 10.000 anni), come metafora di eternità e quindi di potenza, ma il loro unico vero scopo era quello di arginare il grande buio, di spingere l’uomo a progettare nonostante la morte, a pensare al di là non solo del contingente, ma della propria vita, cosa che, a quanto ne sappiamo, è la vera caratteristica unica dell’homo sapiens sapiens.

Adesso, nella nostra civiltà che evolve rapidamente, non siamo più abituati a pensare e a progettare in questi termini di tempo. Quale fra le cose costruite nel dopoguerra è stata progettata per durare 639 anni? Certamente non il condominio in cui vivo, ma nemmeno grandi cose come il nuovo aeroporto di Tokyo o Postdamer Platz a Berlino.

In realtà, mi chiedo se lo abbiamo mai fatto. Molto probabilmente i romani, quando costruivano arene e acquedotti, non immaginavano che sarebbero state ancora qui dopo più di 2000 anni e gli stessi costruttori della più grande opera in muratura della storia, la Grande Muraglia, non costruivano certo per i millenni, ma solo per tener lontani i barbari, peraltro con scarsi risultati. Mi chiedo anche se i progettisti delle piramidi guardassero ai millenni chiudendo gli occhi e immaginando la piana di Giza o pensassero solo a una tomba imponente per il faraone/dio.

Paradossalmente, le uniche opere moderne progettate per durare non secoli, ma decine di millenni non sono destinate alla gloria della specie umana, ma alla testimonianza della sua idiozia: sono i depositi delle scorie radioattive che decadono in 10 o 20.000 anni o il sarcofago di Chernobyl che racchiude 190 tonn. di uranio e una di plutonio, mortali per chiunque si avvicini.

Il Cage-OrgelProjekt, invece, è una costruzione culturale che non ha bisogno di grandi mezzi, ma è specificamente progettata sulla durata.

Una delle cose più intriganti di questo progetto, sempre ammesso che riesca, è proprio questa. Ripeto, 639 anni sono un sacco di tempo. Come cambieranno il mondo e la stessa razza umana in tutto questo tempo? Chi ci sarà, se mai ci sarà qualcuno, a vedere il rilascio dell’ultimo tasto? Sarà ancora umano?

E poi, che significato assumerà questo luogo in cui risuona un eterno bordone, fra 3 o 400 anni? E cosa ci sarà intorno? Sembrano domande banali, ma pensando alle sfide che ci aspettano, riscaldamento globale, conflitti economici, risorse naturali, ma anche tecnologia, spazio, ingegneria genetica, etc, mi fa un po’ rabbia il non saperlo.

Penso anche che la cappella di St. Burchardi e il suo eterno bordone siano un buon tema per un racconto di fantascienza (ho suggerito agli organizzatori di creare un concorso).

Qualcuno dice che una vita troppo lunga non ha senso, ma essere fra il pubblico alla fine mi piacerebbe, credetemi. Firmerei subito. Ho le mie ragioni.

Qui il sito del Cage-OrgelProjekt