È troppo bella…

- Alfred Schnitke (1934 – 1998) – Stille Nacht per violino e pianoforte (1978)

È troppo bella…

Natale si avvicina e per me le feste comandate sono periodi nefandi e depressi, così cerco di addolcirle con un po’ di musica, magari a tema, ma diversa dal solito.

George Crumb ha scritto questa Little Suite for Christmas per piano solo nel 1980.

Si tratta di un brano dolce e silenzioso, ma nello stesso tempo molto energico, giocato su un dialogo fra suono e silenzio, con eruzioni sonore, lunghe pause e frasi esitanti.

Qui Crumb rinuncia all’amplificazione e agli oggetti inseriti su/fra le corde che usava nel Makrokosmos, ma si concentra sul suono dello strumento, con corde lasciate vibrare, pedali, armonici, risonanze e pizzicati.

Il risultato è contemplativo e affascinante. Un pezzo che mostra come si possa scrivere musica contemporanea ma accessibile e godibile nello stesso tempo.

Trovato sul solito YouTube il video originale (1969) di Delusion of the Fury di Harry Partch.

La qualità non è della migliore, ma tant’è…

The Staging of Delusion of the Fury showing the Harry Partch’s instrumentarium.

Ensemble Musikfabrik

Di Harry Partch abbiamo già parlato su queste pagine. Artista personalissimo, a cavallo fra il ‘900 storico e il contemporaneo (1901-1974), capace di ideare e costruire una propria strumentazione che non si basa sul temperamento equabile e per questo isolato, ma ciò nonostante sempre presente a sé stesso e consapevole del suo essere compositore (ricordiamo che durante la grande depressione vagava come un senzatetto e tuttavia era in grado di pubblicare un giornaletto dal titolo Bitter Music – Musica Amara), Partch ha sempre portato avanti la sua sfida all’estetica corrente, quale essa fosse.

Con la sua musica, non tonale, non atonale, ma anzi completamente esterna a questo dualismo, (sviluppando quell’atteggiamento prettamente americano che già troviamo in Ives e altri), Harry Partch raggiunge livelli di grande potenza, come in questa ultima opera del 1965-66, eseguita una sola volta mentre era ancora in vita.

Delusion of the Fury: A Ritual Of Dream And Delusion, per 25 strumenti (mai utilizzati tutti insieme), 4 cantanti e 6 attori/ballerini/mimi, accosta un dramma giapponese nel primo atto a una farsa africana nel secondo, realizzando quel concetto di teatro totale che integra musica, danza, arte scenica e rituale da sempre caro all’autore.

L’opera non ha un vero e proprio libretto, nel senso narrativo dell’opera europea. Tutta l’azione è danzata e/o mimata.

Nelle parole di Partch, il primo atto è sostanzialmente un’uscita dall’eterno ciclo di nascita e morte rappresentato dal pellegrinaggio di un guerriero in cerca di un luogo sacro in cui scontare la penitenza per un omicidio, mentre l’ucciso appare nel dramma come spettro, dapprima a rivivere e far rivivere al suo assassino il tormento dell’omicidio, trovando infine una riconciliazione con la morte nelle parole “Prega per me!”.

Il secondo atto è invece una riconciliazione con la vita che passa attraverso la disputa, nata per un equivoco, fra un hobo sordo e una vecchia che cerca il figlio perduto. Alla fine, i due vengono trascinati di fronte a un confuso giudice di pace sordo e quasi cieco che, equivocando a sua volta, li scambia per marito e moglie e intima loro di tornare a casa, mentre il coro intona all’unisono un ironico inno (“come potremmo andare avanti senza giustizia?”) e la disputa si stempera nell’assurdità della situazione.

L’opera si conclude con stessa invocazione del finale del primo atto (“Pray for me, again”), lanciata da fuori scena.

Qui il video originale

Le “Eight Songs for a Mad King” scritte da Peter Maxwell Davies nel 1969, sono ispirate alla follia senile di re Giorgio III° di Gran Bretagna e a un carillon, tuttora esistente e appartenente a Sir Stephen Runciman, che si racconta venisse usato dal re nella pretesa di insegnare a cantare agli uccelli del parco.

Si tratta in realtà di un monodramma di circa 30 minuti con libretto di Randolf Stow basato su testi dello stesso Giorgio III° (testi qui), pensato per l’attore e cantante sudafricano Roy Hart, baritono dall’enorme estensione vocale (più di 5 ottave) e proprio per questo raramente eseguita in seguito (Roy Hart, morì in un incidente poco dopo la prima).

La partitura è per flauto (+ottavino), clarinetto, violino, violoncello, pianoforte (+clavicembalo, dulcimer), percussioni (+vari fischietti, didjeridu), oltre all’attore protagonista che è l’unico a muoversi liberamente sul palcoscenico, essendo gli altri esecutori rinchiusi in grandi uccelliere.

Nel corso dell’opera, il re dialoga anche individualmente con gli altri strumenti che a volte incarnano le sue allucinazioni: p.es. il flauto diventa la Lady-in-Waiting del terzo brano, mentre il violoncello rappresenta il Tamigi nel brano no. 4 e il percussionista è il custode del re.

Un’opera innovativa nel 1969, anche dal punto di vista grafico, che a tratti incorpora musica di corte dell’epoca.

Here with the score

and here with the scenic action

Nocturnal è uno degli ultimi brani di Edgar Varèse (1883-1965), lasciato incompiuto e terminato dal suo allievo e assistente Chou Wen-chung nel 1968 facendo, a mio avviso, un ottimo lavoro (non si avverte la mano di qualcun altro).

Ecco un estratto delle note di programma.

Nocturnal is a world of sounds remembered and imagined, conjuring up sights and moods now personal, now Dantesque, now enigmatic. Perhaps one should not read too much into a composer’s choice of words, but how, knowing Varèse’s unique career, could one resist wondering about the line, ‘I rise, I always rise after crucifixion’? What about the mocking, threatening, babbling emanations from the chorus, often directed to sound ‘as if from underground’ and ‘harsh’? Then there are the sounds remembered — the liquid beat on the wood block, the shrill whistling of the winds, the tenacious shimmering of the strings — the insistent sound of a mass of shuffling feet, the flourishes of drum beats, the sudden crashing outbursts. A phantasmagorical world? Yes, but as real as Varèse’s own life.

In completing the score … two principles were followed: (1) continuation of some of Varèse’s principal material of the original portion, following suggestions in his cryptic notes; (2) addition of new material from the few more elaborate sketches found, so as to illustrate more fully his ideas for this work and his concepts in the use of vocal sounds. All the details, whenever not specified in the sketches, are worked out according to the original portion or other sketches in which similar situations are found. The original portion ends with the words, ‘dark, dark, dark, asleep, asleep,’ sung by the soprano. This is clearly indicated in the published score. The added portion is purposely kept to the minimum length possible, just enough to include all suitable additional material and to provide structural coherence.

[Chou Wen-chung ]

The word alap refers to the opening passage of Raga music. In the music of India, the alap tends to display improvisational materials which relate to the music which will follow, yet it contains a deep expressivity. In the work Grand Alap, the opening passage serves as a kind of ritual offering to all surrounding spirits and is a request for permission to begin the performance. This practice has occurred in the music-making practices of cultures throughout parts of Asia for many centuries, including Cambodia. The subtitle ‘A Window in the Sky’ is a reference to the recent scientific discovery of hundreds of newly found galaxies (with the assistance of the Hubble telescope) and perhaps relates to the expository quality of the work, and its expansiveness.

Grand Alap requires the percussionist to be male and the cellist to be female, as each of them has a vocal part which is both separate and related to their instrumental parts. Each of them is required to articulate certain phonemes as well as to sing. Some of the phonemes used are derivative of the sounds used to communicate percussion techniques in regions of South and Southeast Asia while others resemble words in a few ancient languages. A few words have meaning in the Khmer (Cambodian) language, which derives from Pali and Sanskrit: ‘Soriya’ is the sun, ‘Mekhala’ is the goddess of water, and the words ‘Mehta/Karona’ refer to the concept of greater compassion.

Grand Alap consists of countless fragments strung together like beads on a necklace in a complete circle. Some of these fragments bear distinct references to particular personae. The sections entitled ‘Entering into Trance’ and ‘In Trance’ require that the percussionist execute those fragments while in a kind of altered state, or as if thrown into an unearthly dimension. In the section entitled ‘An Angel Voice’ the cellist is to sing a musical phrase with a pure and balanced expression, as if coming from a heavenly place. ‘Rising On the Seventh Day’ symbolizes a ‘rebirth’ of the soul, which is a reference to traditional Khmer theatre, and ‘Departure of the Angel’ is the very last fragment of the work.

The vocal lines in Grand Alap have numerous functions. While at times they are an integral part of the texture and sonority, they also represent the locus of each musical personae or fragment, which are then strung together, as stated before, in a kind of necklace. Sometimes the vocalizations extend instrumental sounds or vice versa while at other times they are interlocked with instrumental sounds. The role of the voices is also often ‘broken’ and detached from the instrumental activity, allowing for instrumental sound to develop alone at certain moments. Instrumental display is continuous throughout the piece, while the voices can be said to contribute dots and dashes, or curves of expressive colors in a painting which emerge out of the canvas. Here, the surface of the canvas is represented by the ever-present instrumental sonority.

Grand Alap was commissioned by Maya Beiser and Steven Schick and made possible by the commissioning program of Meet the Composer/Reader’s Digest. This work grew out of a series of collaborative sessions between the composer and the commissioning performers.

Chinary Ung was born in 1942 in Cambodia and began studying the clarinet in Phnom Penh. He emigrated to the USA in 1964, finishing his clarinet studies and enrolling in composition at Columbia University.

Graduating in 1974, he turned back to his home country, studying Khmer musical traditions for the next decade.

Since 1995 he has taught at the University of California, San Diego.

About his music he says:

I believe that imagination, expressivity, and emotion evoke a sense of Eastern romanticism in my music that parallels some of the music-making in numerous lands of Asia. Above all, in metaphor, if the Asian aesthetic is represented by the color yellow, and the Western aesthetic is represented by the color blue, then my music is a mixture — or the color green.

Chinary Ung – Grand Alap: A Window in the Sky (1996), per violoncello e percussioni

Iva Casian-Lakos, cello, voice – John Ling, percussion, voice

My note:

C’è una interessante estetica che si va sviluppando in anni relativamente recenti: quella di coloro che hanno assorbito ed elaborato elementi culturali lontani e diversi. È qualcosa che va al di la di quello che il pop etichetta banalmente come world music. Non si tratta semplicemente di piazzare una melodia orientale su un ritmo occidentale o viceversa o ancora di suonare rock con lo shamisen.

Se ascoltate questo brano noterete come l’atmosfera oscilli continuamente fra est e ovest, con la sonorità tipicamente occidentale del violoncello, che a tratti si fa orientale con scale e pedali, le percussioni che stanno ora qui ora là e le voci che sono trattate con emissione molto orientale. È un bel mix, frutto di studio, di idee, non banale e non superficiale.

Personalmente, come atteggiamento (non come musica), mi ricorda un po’ Takemitsu quando faceva affiorare atmosfere tipicamente giapponesi da insiemi strumentali del tutto occidentali.

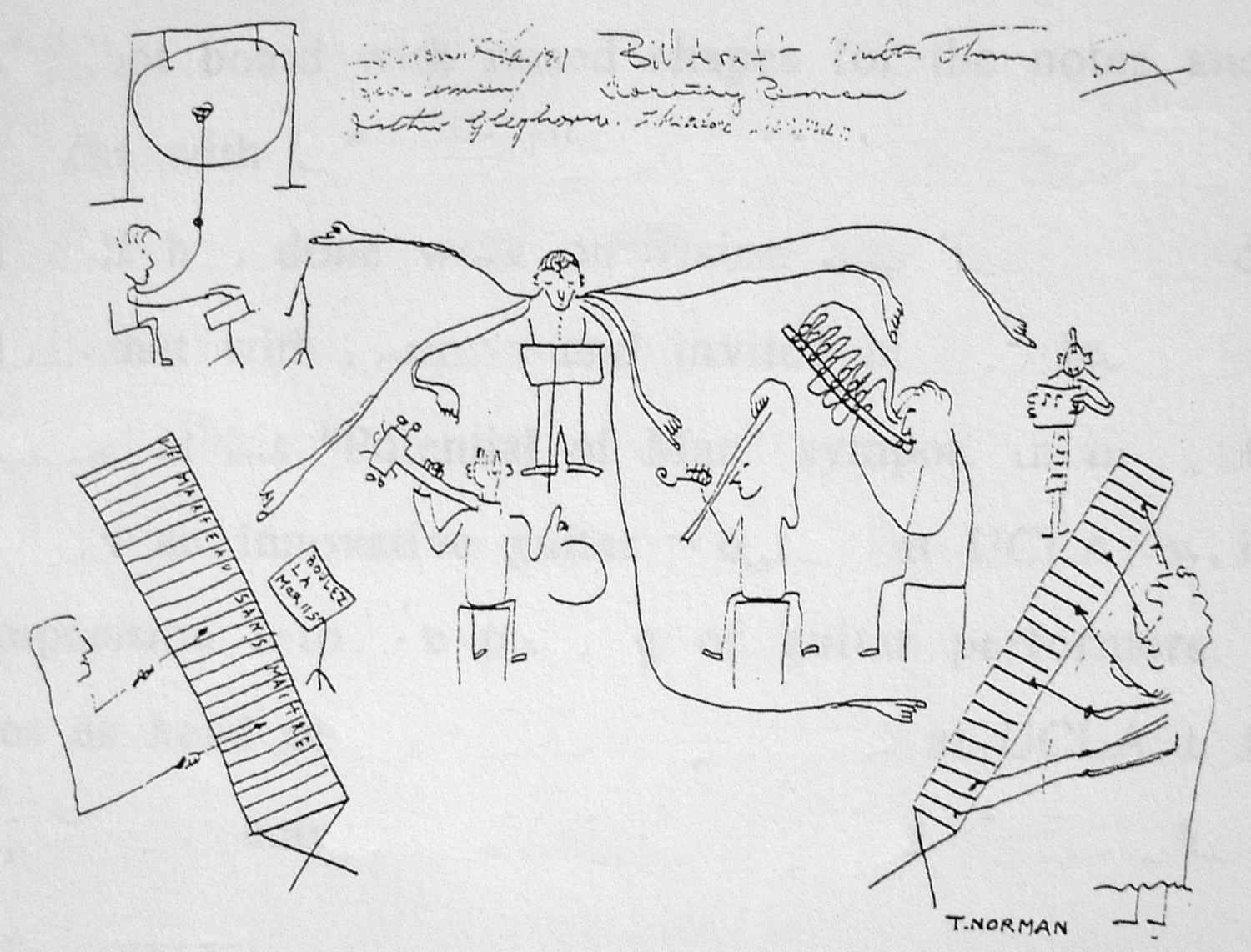

Ted Norman (1912-1997) era un chitarrista e compositore canadese dotato anche di sense of humour.

Infatti, dopo aver partecipato all’esecuzione del Marteau diretto dallo stesso Boulez, ha prodotto lo schizzo che vedete sotto e che trovate qui in dimensioni originali.

George Crumb – An Idyll for the Misbegotten (1986)

per flauto amplificato e 3 percussioni

Kristen Halay flauto, Brian Scott, W. Sean Wagoner, Tracy Freeze percussioni

I feel that ‘misbegotten’ [trad: figlio illegittimo, bastardo] well describes the fateful and melancholy predicament of the species homo sapiens at the present moment in time. Mankind has become ever more ‘illegitimate’ in the natural world of plants and animals. The ancient sense of brotherhood with all life-forms (so poignantly expressed in the poetry of St. Francis of Assisi) has gradually and relentlessly eroded, and consequently we find ourselves monarchs of a dying world. We share the fervent hope that humankind will embrace anew nature’s ‘moral imperative.’

[George Crumb]

Crumb suggests, “impractically,” that the music be “heard from afar, over a lake, on a moonlit evening in August.” (Crumb) Over a slow bass drum tremolo, the flute begins its haunting melody, which over the course of the piece includes quotations of Claude Debussy’s solo flute piece Syrinx and spoken verse by the eighth-century Chinese poet Ssu-K’ung Shu: “The moon goes down. There are shivering birds and withering grasses.” Far from a traditionally peaceful idyll, the music’s energy and dynamics gradually rise and fall, with a sense of desolation throughout.

Black Angels (Images I), quartetto d’archi amplificati di George Crumb, probabilmente l’unico quartetto ispirato alla guerra in Vietnam. È una bella partitura, anche graficamente. I titoli dei movimenti, poi, sono fantastici (mi piace molto il 2.3 “Sarabanda de la Muerte Oscura”).

Movements

I. DEPARTURE

II. ABSENCE

III. RETURN

Program Notes (from the author’s site)

Black Angels (Images I)

Thirteen images from the dark land

Things were turned upside down. There were terifying things in the air … they found their way into Black Angels. – George Crumb, 1990

Black Angels is probably the only quartet to have been inspired by the Vietnam War. The work draws from an arsenal of sounds including shouting, chanting, whistling, whispering, gongs, maracas, and crystal glasses. The score bears two inscriptions: in tempore belli (in time of war) and “Finished on Friday the Thirteenth, March, 1970”.

Black Angels was conceived as a kind of parable on our troubled contemporary world. The numerous quasi-programmatic allusions in the work are therefore symbolic, although the essential polarity — God versus Devil — implies more than a purely metaphysical reality. The image of the “black angel” was a conventional device used by early painters to symbolize the fallen angel.

The underlying structure of Black Angels is a huge arch-like design which is suspended from the three “Threnody” pieces. The work portrays a voyage of the soul. The three stages of this voyage are Departure (fall from grace), Absence (spiritual annihilation) and Return (redemption).

The numerological symbolism of Black Angels, while perhaps not immediately perceptible to the ear, is nonetheless quite faithfully reflected in the musical structure. These “magical” relationships are variously expressed; e.g., in terms of length, groupings of single tones, durations, patterns of repetition, etc. An important pitch element in the work — descending E, A, and D-sharp — also symbolizes the fateful numbers 7-13. At certain points in the score there occurs a kind of ritualistic counting in various languages, including German, French, Russian, Hungarian, Japanese and Swahili.

There are several allusions to tonal music in Black Angels: a quotation from Schubert’s “Death and the Maiden” quartet (in the Pavana Lachrymae and also faintly echoed on the last page of the work); an original Sarabanda, which is stylistically synthetic; the sustained B-major tonality of God-Music; and several references to the Latin sequence Dies Irae (“Day of Wrath”). The work abounds in conventional musical symbolisms such as the Diabolus in Musica (the interval of the tritone) and the Trillo Di Diavolo (the “Devil’s Trill”, after Tartini).

The amplification of the stringed instruments in Black Angels is intended to produce a highly surrealistic effect. This surrealism is heightened by the use of certain unusual string effects, e.g., pedal tones (the intensely obscene sounds of the Devil-Music); bowing on the “wrong” side of the strings (to produce the viol-consort effect); trilling on the strings with thimble-capped fingers. The performers also play maracas, tam-tams and water-tuned crystal goblets, the latter played with the bow for the “glass-harmonica” effect in God-Music.

George Crumb – Black Angels (Images I) performed by the Miró Quartet Daniel Ching (violin), Sandy Yamamoto (violin), John Largess (viola), Joshua Gindele (cello)