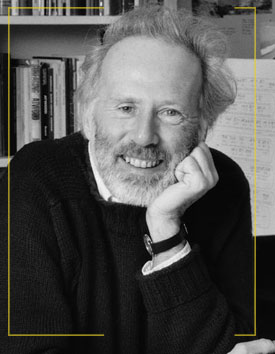

George Crumb è uno dei compositori che ho sempre amato. È uno dei pochi contemporanei che trovo emozionanti. Uno dei pochi che non scrivono solo ‘esercizi’ o ‘studi’.

Di questo brano ho già parlato, proprio qui, più o meno 9 anni fa. Ma allora non c’era la diffusione offerta dal libro di facce e non c’erano i video del tubo (non come adesso, almeno). Così ne approfitto per rimettere qualcosa, questa volta con il video dell’esecuzione e note dell’autore.

George Crumb, Zeitgeist, Six Tableaux for Two Amplified Pianos (Book I) (1987, rev. 1989)

I. Portent – Molto moderato, il ritmo ben marcato

II. Two Harlequins – Vivace, molto capriccioso

III. Monochord – Lentamente, misterioso

IV. Day of the Comet – Prestissimo

V. The Realm of Morpheus (“. . . the inner eye of dreams”)

Piano I: Lentamente quasi lontano, sognante

Piano II: Adagio sospeso, misterioso

VI. Reverberations – Molto moderato, il ritmo ben marcato

Alexander Ghindin & Boris Berezovsky Amplified pianos

Notes from the author:

Zeitgeist (Six Tableaux for Two Amplified Pianos, Book I) was composed in 1987. The work was commissioned by the European piano-duo team of Peter Degenhardt and Fuat Kent, who subsequently gave the premiere performance at the Charles Ives Festival in Duisburg, Germany on January 17, 1988. Zeitgeist was extensively revised after this initial performance.

For a German-speaking person, the expression “Zeitgeist” has a certain portentous and almost mystical significance, which is somewhat diluted in our English equivalent: “spirit of the time.”

The title seemed to me especially appropriate since the work does, I feel, touch on various concerns which permeate our late-twentieth century musical sensibility. Among these, I would cite: the quest for a new kind of musical primitivism: (a “morning of the world” vision of the elemental forms and forces of nature once again finding resonance in our music); an obsession with more minimalistic (or at least, more simple and direct) modes of expression; the desire to reconcile and synthesize the rich heritage of our classical Western music with the wonderfully vibrant ethnic and classical musics of the non-Western world; and, finally, our intense involvement with acoustical phenomena and the bewitching appeal of timbre as a potentially structural element.

In many of its aspects—compositional technique, exploitation of “extended-piano” resources, and emphasis on poetic content—Zeitgeist draws heavily from my earlier piano compositions, especially the larger works of my Makrokosmos cycle (Music for a Summer Evening [1974] for two amplified pianos and percussion, and Celestial Mechanics [1979J for amplified piano, four-hands).

The opening movement of Zeitgeist, entitled Portent, is based primarily on six-tone chordal structures and a rhythmically incisive thematic element. The music offers extreme contrasts in register and dynamics. A very characteristic sound in the piece is a mysterious glissando effect achieved by sliding a glass tumbler along the strings of the piano while the keys are being struck.

The second movement—Two Harlequins—is extremely vivacious and whimsical. The music is full of mercurial changes of mood and comical non sequiturs. Although this piece is played entirely on the keyboard, an echoing ambiance resonates throughout.

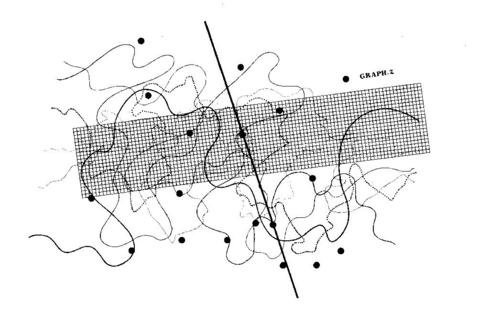

Monochord (which in the score is notated in a symbolic circular manner) is based entirely on the first 15 overtones of a low B-flat. A continuous droning sound (produced alternately by the two pianists) underlies the whole piece. This uncanny effect, produced by a rapid oscillating movement of the fingertip in direct contact with the string, results in a veritable rainbow of partial tones. In addition, paper strips placed over the lower ten strings of each piano produce an almost sizzling effect.

The title of the fourth movement —Day of the Comet— was suggested by the recent advent of Halley’s comet (the previous visitation was commemorated by H. G. Wells in his science fiction novel of the same title). The piece, played at prestissimo tempo and consisting of polyrhythmic bands of chromatic clusters, is volatile, yet strangely immaterial.

Perhaps Debussy’s Feux d’artifice (Preludes, Book II) is the spiritual progenitor of this genre of composition.The fifth movement —The Realm of Morpheus— is like Monochord symbolically notated. The bent staves take on the perceptible configuration of the human eye (“…the inner eye of dreams”). Each of the two pianists plays independently, and the combined musics express something shadowy and ill-defined—like the mysterious subliminal images which appear in dreams.

Disembodied fragments of an Appalachian folk-song (“The Riddle”) emerge and recede.The concluding movement of the work —Reverberations— recalls the principal thematic and harmonic elements of the first movement. This piece is constructed in its entirety on the “echoing phenomenon”—that most ancient of musical devices.

[George Crumb]

R. Murray Schafer – Snowforms (1982) – for treble choir

R. Murray Schafer – Snowforms (1982) – for treble choir

Dal fascinoso Zodiac, del percussionista inglese

Dal fascinoso Zodiac, del percussionista inglese

“Music,” says Toshio Hosokawa, “is the place where notes and silence meet.” This identifies his aesthetic concept as a genuinely Japanese one. It is found both in Japanese landscape painting and in the music, such as the courtly gagaku, in which audible sound always stands in relation to nonsound, i.e. to silence. In their rhythmic proportions Hosokawa’s compositions are oriented around the breathing methods of Zen meditation, with their very slow breathing in and very slow breathing out: “Each breath contains life and death, death and life.”

“Music,” says Toshio Hosokawa, “is the place where notes and silence meet.” This identifies his aesthetic concept as a genuinely Japanese one. It is found both in Japanese landscape painting and in the music, such as the courtly gagaku, in which audible sound always stands in relation to nonsound, i.e. to silence. In their rhythmic proportions Hosokawa’s compositions are oriented around the breathing methods of Zen meditation, with their very slow breathing in and very slow breathing out: “Each breath contains life and death, death and life.”

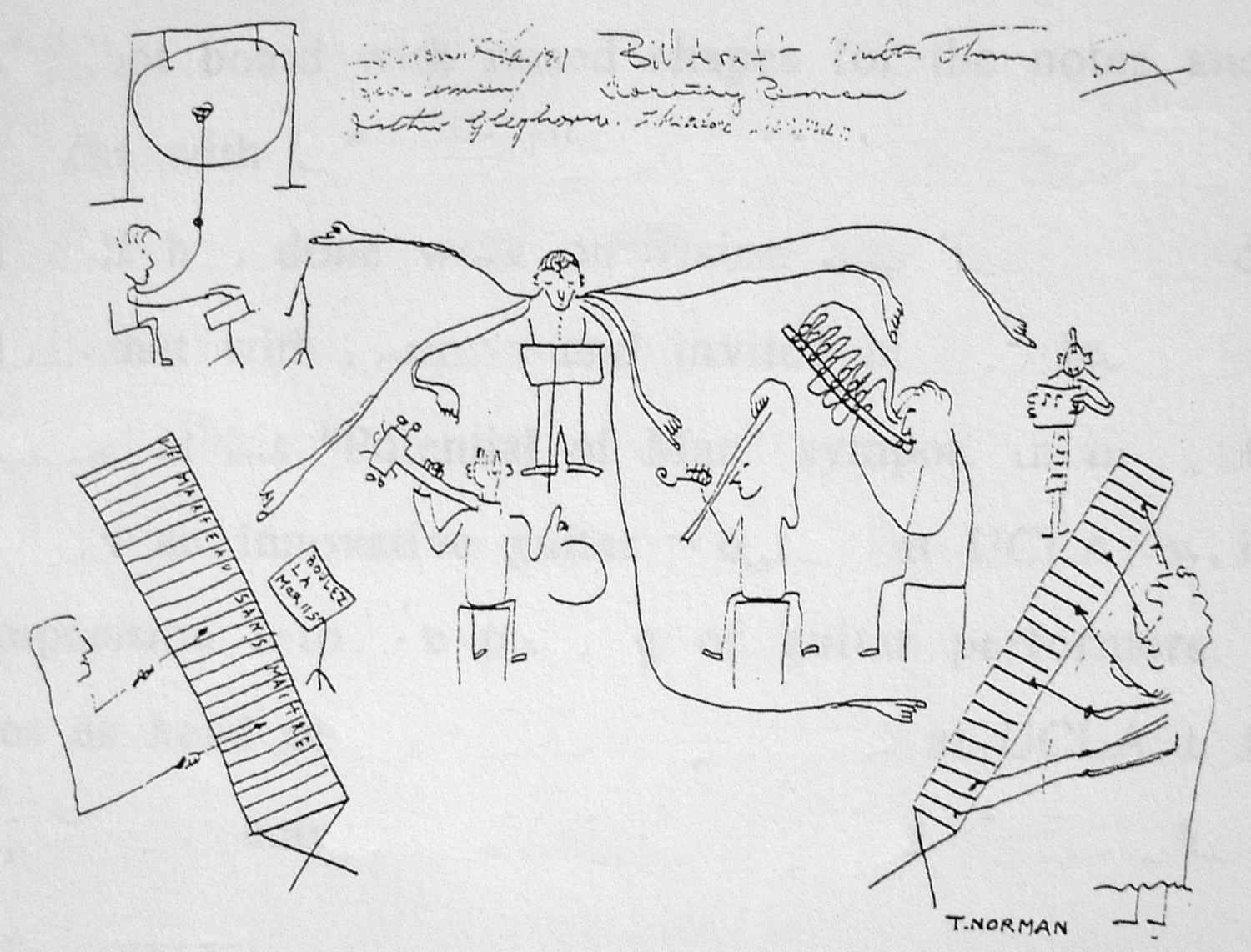

Negli anni ’70, Cornelius Cardew, fino ad allora uno dei più importanti compositori inglesi, pioniere dell’utilizzo di partiture grafiche e dell’improvvisazione, assistente di Stockhausen dal 1958 al 1960, ebbe una improvvisa conversione politica al Comunismo (per la precisione aderì al

Negli anni ’70, Cornelius Cardew, fino ad allora uno dei più importanti compositori inglesi, pioniere dell’utilizzo di partiture grafiche e dell’improvvisazione, assistente di Stockhausen dal 1958 al 1960, ebbe una improvvisa conversione politica al Comunismo (per la precisione aderì al  Era tempo che qualcuno diffondesse una nuova versione di alcuni brani del ciclo

Era tempo che qualcuno diffondesse una nuova versione di alcuni brani del ciclo  The new album by

The new album by  Octandre è rappresentativo di un modo di comporre tipico di Edgar Varèse, sviluppando e variando piccoli frammenti sonori. Lo stesso compositore lo descrive mediante una analogia con la crescita di un cristallo.

Octandre è rappresentativo di un modo di comporre tipico di Edgar Varèse, sviluppando e variando piccoli frammenti sonori. Lo stesso compositore lo descrive mediante una analogia con la crescita di un cristallo. …consiste nel fatto che un uomo corpulento, gioviale e ciarliero si metta a scrivere della musica ai limiti dell’udibile. In un secolo rumoroso come il nostro, Morton Feldman ha scelto di essere silenzioso e soffice come la neve.

…consiste nel fatto che un uomo corpulento, gioviale e ciarliero si metta a scrivere della musica ai limiti dell’udibile. In un secolo rumoroso come il nostro, Morton Feldman ha scelto di essere silenzioso e soffice come la neve.

Ylem è un termine usato da

Ylem è un termine usato da  Uno dei desideri di

Uno dei desideri di  Bellissimo e spiazzante è ciò che il compositore dice del silenzio, che abbonda in quest’opera:

Bellissimo e spiazzante è ciò che il compositore dice del silenzio, che abbonda in quest’opera:

Jacob Sudol è un giovane compositore americano. Giovane davvero, una volta tanto, essendo nato a Des Moines, Iowa, nel 1980.

Jacob Sudol è un giovane compositore americano. Giovane davvero, una volta tanto, essendo nato a Des Moines, Iowa, nel 1980. Wolfang Rihm è una figura abbastanza importante nella musica contemporanea tedesca. Nato nel 1952 a Karlsruhe, di formazione musicale tradizionale, pur avendo poi studiato con Stockhausen non aderì mai completamente allo sperimentalismo di Darmstadt e Donaueschingen.

Wolfang Rihm è una figura abbastanza importante nella musica contemporanea tedesca. Nato nel 1952 a Karlsruhe, di formazione musicale tradizionale, pur avendo poi studiato con Stockhausen non aderì mai completamente allo sperimentalismo di Darmstadt e Donaueschingen.

Oltre a quello di Messiaen, c’è un secondo centenario quest’anno: quello della nascita del compositore americano

Oltre a quello di Messiaen, c’è un secondo centenario quest’anno: quello della nascita del compositore americano

Difficile scrivere poche righe su

Difficile scrivere poche righe su  L’ho ascoltato guardando l’indicatore del traffico di rete che mostrava kili e kili di zeri viaggiare da MySpace al mio computer.

L’ho ascoltato guardando l’indicatore del traffico di rete che mostrava kili e kili di zeri viaggiare da MySpace al mio computer.

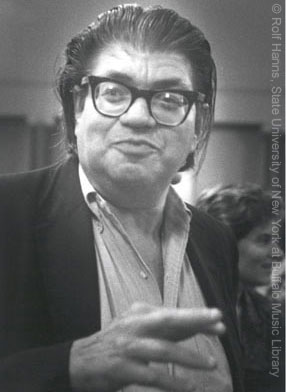

Maderna (nella foto, con Berio) è morto il 13 Novembre 1973 a soli 53 anni.

Maderna (nella foto, con Berio) è morto il 13 Novembre 1973 a soli 53 anni.

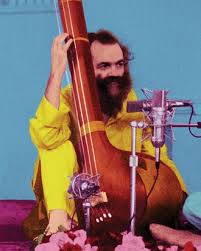

Il rivolgersi a oriente tipico della seconda metà degli anni ’60 coinvolge anche Stockhausen che, nel fatidico 1968, abbraccia con decisione le filosofie orientali. Passando attraverso Stimmung, giungerà gradualmente alla definizione di una musica intuitiva, praticamente priva di partitura

Il rivolgersi a oriente tipico della seconda metà degli anni ’60 coinvolge anche Stockhausen che, nel fatidico 1968, abbraccia con decisione le filosofie orientali. Passando attraverso Stimmung, giungerà gradualmente alla definizione di una musica intuitiva, praticamente priva di partitura Questo non significa che tutta l’opera, che dura ben 70 minuti, sia costituita da un unico accordo, ma quasi. Un accordo di 6 note implica una gamma di possibilità che va dalle singole note fino ad accordi composti di 2, 3, 4, 5 e finalmente 6 note. Inoltre, ogni nota può essere potenzialmente eseguita da più di un cantante (tutti dovrebbero poter cantare il RE).

Questo non significa che tutta l’opera, che dura ben 70 minuti, sia costituita da un unico accordo, ma quasi. Un accordo di 6 note implica una gamma di possibilità che va dalle singole note fino ad accordi composti di 2, 3, 4, 5 e finalmente 6 note. Inoltre, ogni nota può essere potenzialmente eseguita da più di un cantante (tutti dovrebbero poter cantare il RE).