Winter Leaves è una investigazione sui rapporti che intercorrono fra armonia e timbro.

Winter Leaves, infatti, si basa su 3 suoni, ognuno formato da 5 sinusoidi le cui frequenze hanno fra loro un intervallo fisso. Tutti suoni sono costruiti sulla stessa fondamentale (47.5 Hz, circa SOL). Le altre 4 componenti hanno rapporti di 2 (8va) nel primo suono, di 2.24 (9a magg.) nel secondo e 2.8856 (intervallo non temperato corrispondente a una 11ma crescente) nel terzo.

I 3 suoni base, quindi, hanno le seguenti componenti sinusoidali:

- Rapporto 2 -> 47.5, 95, 190, 380, 760 (8ve sovrapposte)

- Rapporto 2.24 -> 47.5, 106.4, 238.3, 533.9, 1195.9 (9ne sovrapposte)

- Rapporto 2.8856 -> 47.5, 137.1, 395.5, 1141.3, 3293.4 (11me cresc. sovrapposte).

A questo punto è chiaro che spettri di questo tipo possiedono sia una valenza timbrica che armonica. Nel primo caso il suono è associato alla consonanza perfetta, nel secondo, a una dissonanza interpretabile nell’ambito del sistema temperato e nel terzo a una dissonanza non temperata.

Ognuno di questi spettri, sintetizzato con una semplice additiva a 5 oscillatori, viene poi arricchito dal punto di vista acustico grazie a un processo di ring modulation fra le 5 componenti base prese 2 a 2. Con questo metodo si generano altre componenti le cui frequenze sono pari alla somma e alla differenza fra quelle di base, come è tipico del modulatore ad anello. Si ottengono, così, altre frequenze che vengono utilizzate sia come componenti spettrali che come ‘note’ su cui articolare il discorso melodico/armonico.

Ne consegue che il rapporto 2 genera, per somma e differenza, solo componenti armoniche; il 2.24 genera un mix di componenti armoniche e inarmoniche e il 2.8856 genera solo componenti inarmoniche.

Nella seguente tabella sono riportati i 3 insiemi di frequenze che possono essere visti sia come organizzazione melodico/armonica che timbrica. In effetti, Winter Leaves è totalmente costruito su di essi in quanto:

- la tessitura melodico/armonica è basata sui 3 insiemi considerati come scale, usate nella maggior parte dei casi da sole e sovrapposte solo nelle fasi di passaggio fra un insieme e l’altro (passaggi, che, comunque, sono molto frequenti nel corso del brano)

- la tessitura timbrica utilizza solo queste frequenze come componenti sinusoidali dei suoni, anche qui un insieme alla volta (non esiste un suono che sia un mix di frequenze provenienti da più insiemi) con sovrapposizioni nei punti di passaggio. Per ottenere queste sonorità sono state programmate in Music360 (l’antenato di CSound) 3 tipologie di strumenti:

- sintesi additiva sulle 5 componenti base (genera solo le componenti blu, sfondo giallo)

- sintesi ring modulation fra una o più coppie di frequenze base (genera le componenti rosse con o senza le coppie generatrici)

- varie combinazioni dei 2 suddetti, fino a uno strumento che genera un suono contenente tutte le frequenze di un insieme

Esistono, quindi, sia spettri con una organizzazione di tipo normale in cui le componenti più basse sono anche le più forti e l’ampiezza cala andando verso gli acuti, che spettri a bande laterali in cui le componenti centrali hanno maggiore ampiezza.

| Ratio 2 |

Ratio 2.24 |

Ratio 2.8856 |

|||

| Freq. Base |

Freq. ± | Freq. Base |

Freq. ± | Freq. Base |

Freq. ± |

| 1140.0 | 1729.7 | 4434.7 | |||

| 950.0 | 1434.2 | 3688.9 | |||

| 855.0 | 1302.3 | 3430.4 | |||

| 807.5 | 1243.4 | 3340.9 | |||

| 760.0 | 1195.9 | 3293.4 | |||

| 712.5 | 1148.4 | 3245.9 | |||

| 665.0 | 1089.5 | 3156.3 | |||

| 570.0 | 957.5 | 2897.8 | |||

| 570.0 | 772.2 | 2152.0 | |||

| 475.0 | 662.0 | 1536.8 | |||

| 427.5 | 640.3 | 1278.4 | |||

| 380.0 | 581.4 | 1188.8 | |||

| 380.0 | 533.9 | 1141.3 | |||

| 332.5 | 486.4 | 1093.8 | |||

| 285.0 | 427.5 | 1004.2 | |||

| 285.0 | 344.7 | 745.8 | |||

| 237.5 | 295.5 | 532.6 | |||

| 190.0 | 285.8 | 443.0 | |||

| 190.0 | 238.3 | 395.5 | |||

| 142.5 | 190.8 | 348.0 | |||

| 142.5 | 153.9 | 258.5 | |||

| 95.0 | 131.9 | 184.6 | |||

| 95.0 | 106.4 | 137.1 | |||

| 47.5 | 58.9 | 89.6 | |||

| 47.5 | 47.5 | 47.5 |

Analizzando i 3 insiemi si nota che le proprietà delle frequenze base si riflettono nelle frequenze generate per somma e differenza. In particolare:

- il rapporto 2 genera solo componenti armoniche

- il rapporto 2.24 genera sia componenti armoniche che inarmoniche

- il rapporto 2.8856 genera quasi esclusivamente componenti inarmoniche

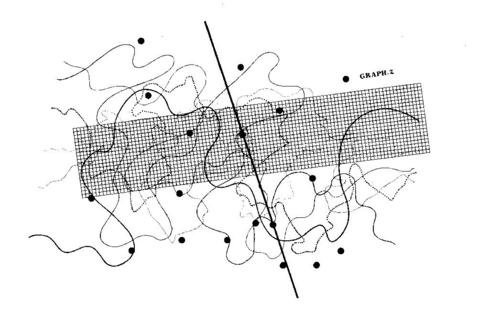

In tal modo è possibile passare gradualmente da campi di suoni armonici a campi di suoni parzialmente o totalmente inarmonici accostando e/o sovrapponendo aree in cui le figurazioni musicali si articolano su insiemi diversi. La seguente immagine evidenzia le aree comuni utilizzabili come ponte.

Winter Leaves ha ottenuto una menzione al 9° International Electroacoustic Music Awards di Bourges (1981) ed è stato analizzato in dettaglio in una tesi di Dottorato in Musique et musicologie du XXème siècle presso l’Université de Paris IV – Sorbonne e Scienze della Musica presso l’Università degli Studi di Trento (XVI ciclo) [Laura Zattra, Science et technologie comme sources d’inspiration au CSC de Padoue et à l’IRCAM de Paris, 2003]. Qui potete leggere un riassunto in italiano dell’analisi tratto dalla suddetta tesi.

Potete ascoltare il brano in streaming cliccando qui. Durata circa 8’30”.

NB: MP3 compresso a bitrate 128. Originale su vinile [ConTempo Musical Editions INSOUND 2 – Record LP Edipan PRC S2016].

R. Murray Schafer – Snowforms (1982) – for treble choir

R. Murray Schafer – Snowforms (1982) – for treble choir

The Beam Drop

The Beam Drop

Dal fascinoso Zodiac, del percussionista inglese

Dal fascinoso Zodiac, del percussionista inglese  La

La  Il

Il

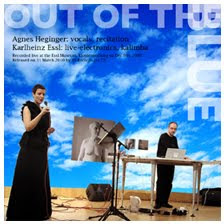

Agnes Heginger, soprano e Karlheinz Essl, elettronico, hanno registrato poco meno di un anno fa, all’Essl Museum in Vienna, questo disco, dal titolo Out of the Blue.

Agnes Heginger, soprano e Karlheinz Essl, elettronico, hanno registrato poco meno di un anno fa, all’Essl Museum in Vienna, questo disco, dal titolo Out of the Blue.

ToBeContinued…

ToBeContinued… The Drawing Center

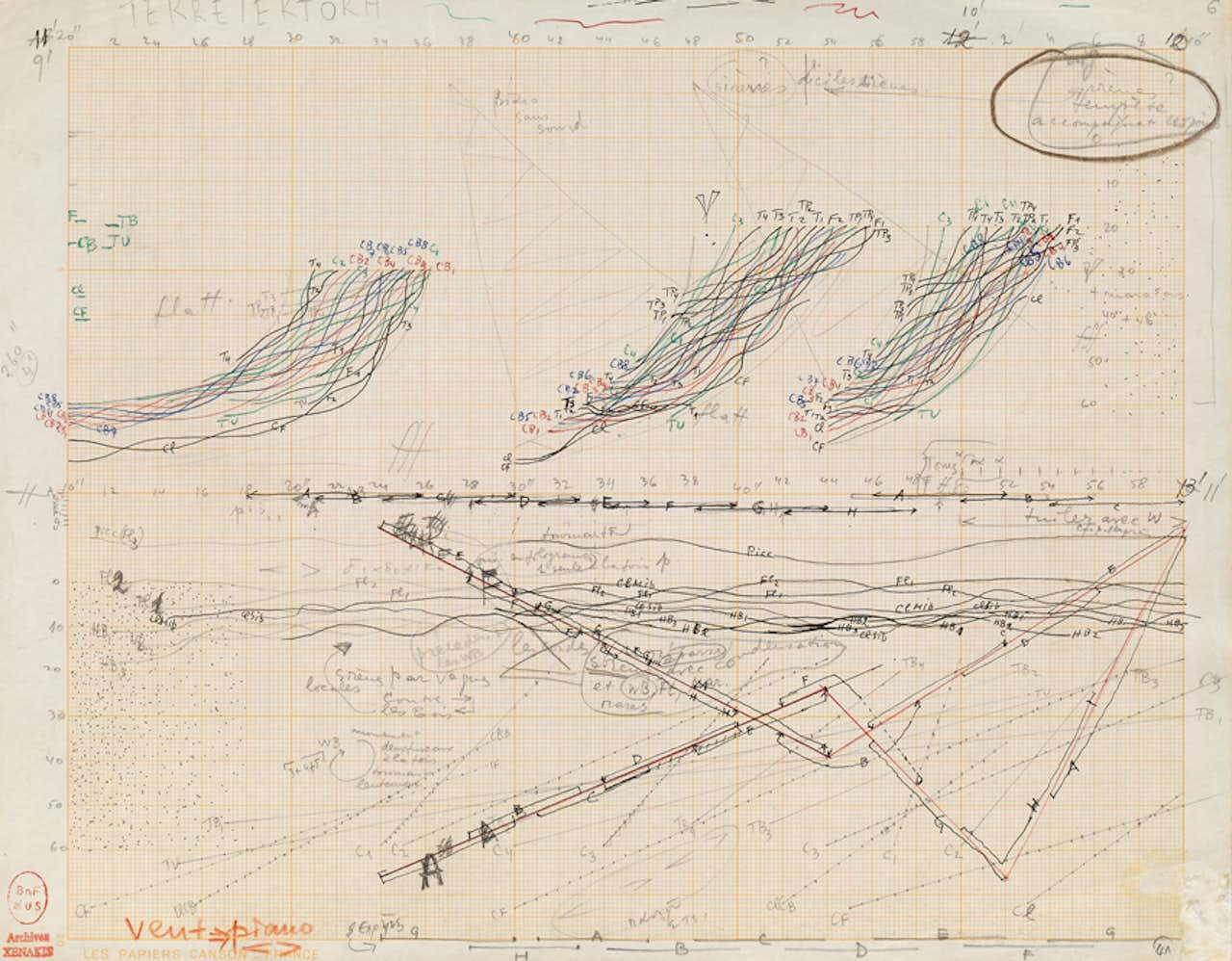

The Drawing Center The sound of Akashic Crow’s Nest begins with the use of an image synthesizer which turns very long photographic images into audio output, in the manner of a piano roll. The initial part of composing this music is thus designing the picture. For this latest project, the first audio output is converted to midi and run through a different softsynth, before being subjected to a battery of effects to get to the sounds you hear on this album.

The sound of Akashic Crow’s Nest begins with the use of an image synthesizer which turns very long photographic images into audio output, in the manner of a piano roll. The initial part of composing this music is thus designing the picture. For this latest project, the first audio output is converted to midi and run through a different softsynth, before being subjected to a battery of effects to get to the sounds you hear on this album.

“Music,” says Toshio Hosokawa, “is the place where notes and silence meet.” This identifies his aesthetic concept as a genuinely Japanese one. It is found both in Japanese landscape painting and in the music, such as the courtly gagaku, in which audible sound always stands in relation to nonsound, i.e. to silence. In their rhythmic proportions Hosokawa’s compositions are oriented around the breathing methods of Zen meditation, with their very slow breathing in and very slow breathing out: “Each breath contains life and death, death and life.”

“Music,” says Toshio Hosokawa, “is the place where notes and silence meet.” This identifies his aesthetic concept as a genuinely Japanese one. It is found both in Japanese landscape painting and in the music, such as the courtly gagaku, in which audible sound always stands in relation to nonsound, i.e. to silence. In their rhythmic proportions Hosokawa’s compositions are oriented around the breathing methods of Zen meditation, with their very slow breathing in and very slow breathing out: “Each breath contains life and death, death and life.”

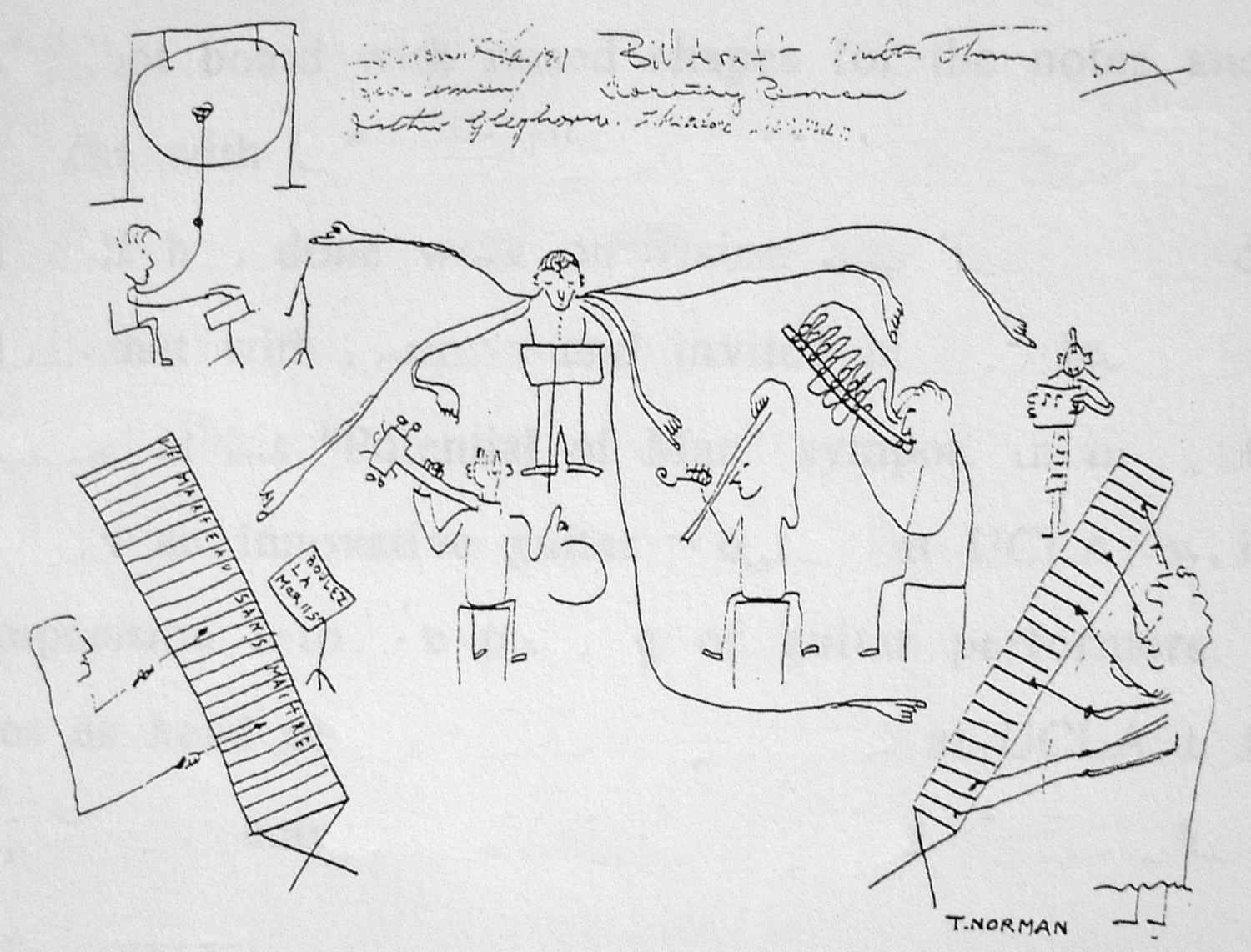

Negli anni ’70, Cornelius Cardew, fino ad allora uno dei più importanti compositori inglesi, pioniere dell’utilizzo di partiture grafiche e dell’improvvisazione, assistente di Stockhausen dal 1958 al 1960, ebbe una improvvisa conversione politica al Comunismo (per la precisione aderì al

Negli anni ’70, Cornelius Cardew, fino ad allora uno dei più importanti compositori inglesi, pioniere dell’utilizzo di partiture grafiche e dell’improvvisazione, assistente di Stockhausen dal 1958 al 1960, ebbe una improvvisa conversione politica al Comunismo (per la precisione aderì al  Era tempo che qualcuno diffondesse una nuova versione di alcuni brani del ciclo

Era tempo che qualcuno diffondesse una nuova versione di alcuni brani del ciclo

The new album by

The new album by  Non è un errore di stampa.

Non è un errore di stampa.  Octandre è rappresentativo di un modo di comporre tipico di Edgar Varèse, sviluppando e variando piccoli frammenti sonori. Lo stesso compositore lo descrive mediante una analogia con la crescita di un cristallo.

Octandre è rappresentativo di un modo di comporre tipico di Edgar Varèse, sviluppando e variando piccoli frammenti sonori. Lo stesso compositore lo descrive mediante una analogia con la crescita di un cristallo.

…consiste nel fatto che un uomo corpulento, gioviale e ciarliero si metta a scrivere della musica ai limiti dell’udibile. In un secolo rumoroso come il nostro, Morton Feldman ha scelto di essere silenzioso e soffice come la neve.

…consiste nel fatto che un uomo corpulento, gioviale e ciarliero si metta a scrivere della musica ai limiti dell’udibile. In un secolo rumoroso come il nostro, Morton Feldman ha scelto di essere silenzioso e soffice come la neve.

Philippe Manoury

Philippe Manoury Un impressionante brano del chitarrista e improvvisatore

Un impressionante brano del chitarrista e improvvisatore

Keith Rowe, forse il prototipo dei chitarristi improvvisatori di scuola anglosassone, esegue un brano di Cornelius Cardew tratto dall’album “A Dimension of Perfectly Ordinary Reality” del 1990.

Keith Rowe, forse il prototipo dei chitarristi improvvisatori di scuola anglosassone, esegue un brano di Cornelius Cardew tratto dall’album “A Dimension of Perfectly Ordinary Reality” del 1990.

Searching the old releases from

Searching the old releases from

Ylem è un termine usato da

Ylem è un termine usato da  20’51” è il nuovo lavoro del compositore colombiano, trasferito a NY,

20’51” è il nuovo lavoro del compositore colombiano, trasferito a NY,  Tripla maledizione, scrivere necrologi è deprimente.

Tripla maledizione, scrivere necrologi è deprimente.

No, non si tratta della sonata 29 op. 106 di Ludwig Van, ma di un recente lavoro elettroacustico di

No, non si tratta della sonata 29 op. 106 di Ludwig Van, ma di un recente lavoro elettroacustico di

Uno dei desideri di

Uno dei desideri di

Bellissimo e spiazzante è ciò che il compositore dice del silenzio, che abbonda in quest’opera:

Bellissimo e spiazzante è ciò che il compositore dice del silenzio, che abbonda in quest’opera:

Jacob Sudol è un giovane compositore americano. Giovane davvero, una volta tanto, essendo nato a Des Moines, Iowa, nel 1980.

Jacob Sudol è un giovane compositore americano. Giovane davvero, una volta tanto, essendo nato a Des Moines, Iowa, nel 1980. Wolfang Rihm è una figura abbastanza importante nella musica contemporanea tedesca. Nato nel 1952 a Karlsruhe, di formazione musicale tradizionale, pur avendo poi studiato con Stockhausen non aderì mai completamente allo sperimentalismo di Darmstadt e Donaueschingen.

Wolfang Rihm è una figura abbastanza importante nella musica contemporanea tedesca. Nato nel 1952 a Karlsruhe, di formazione musicale tradizionale, pur avendo poi studiato con Stockhausen non aderì mai completamente allo sperimentalismo di Darmstadt e Donaueschingen.

Oltre a quello di Messiaen, c’è un secondo centenario quest’anno: quello della nascita del compositore americano

Oltre a quello di Messiaen, c’è un secondo centenario quest’anno: quello della nascita del compositore americano

Il 2008 è il centenario della nascita di

Il 2008 è il centenario della nascita di

Ho visitato

Ho visitato  È morto il compositore

È morto il compositore  Cosa ci fa Alfred Hitchcock sul

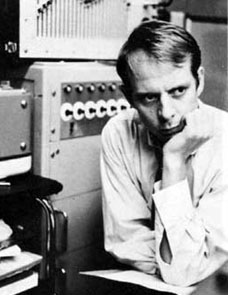

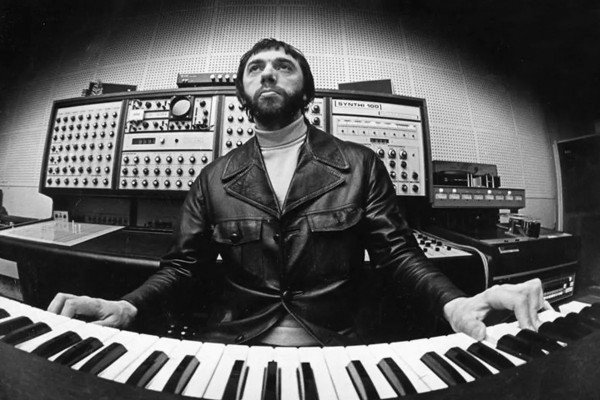

Cosa ci fa Alfred Hitchcock sul  Ecco come si faceva musica elettronica qualche anno fa. Visto che qualcuno di voi ci è nato nel 1982, magari così si fa un’idea.

Ecco come si faceva musica elettronica qualche anno fa. Visto che qualcuno di voi ci è nato nel 1982, magari così si fa un’idea. Post-conceptual digital artist and theoretician Joseph Nechvatal pushes his experimental investigations into the blending of computational virtual spaces and the corporeal world into the sonic register.

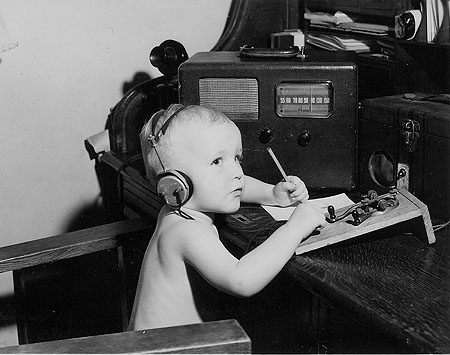

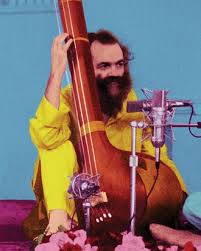

Post-conceptual digital artist and theoretician Joseph Nechvatal pushes his experimental investigations into the blending of computational virtual spaces and the corporeal world into the sonic register. La prima volta che incontrai Barry Truax (nella foto a 2/3 anni), al CSC di Padova alla fine degli anni ’70, io ero uno studente e lui era già un guru della computer music che aveva al suo attivo il POD (un software per la composizione assistita da computer) e una convincente sistematizzazione compositiva della modulazione di frequenza e alcuni brani che la sfruttavano, come Sonic Landscape e Androginy.

La prima volta che incontrai Barry Truax (nella foto a 2/3 anni), al CSC di Padova alla fine degli anni ’70, io ero uno studente e lui era già un guru della computer music che aveva al suo attivo il POD (un software per la composizione assistita da computer) e una convincente sistematizzazione compositiva della modulazione di frequenza e alcuni brani che la sfruttavano, come Sonic Landscape e Androginy. Un buon lavoro questo

Un buon lavoro questo

Difficile scrivere poche righe su

Difficile scrivere poche righe su

L’ho ascoltato guardando l’indicatore del traffico di rete che mostrava kili e kili di zeri viaggiare da MySpace al mio computer.

L’ho ascoltato guardando l’indicatore del traffico di rete che mostrava kili e kili di zeri viaggiare da MySpace al mio computer.

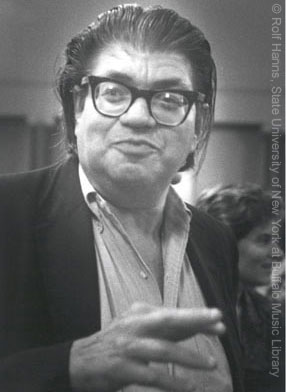

Maderna (nella foto, con Berio) è morto il 13 Novembre 1973 a soli 53 anni.

Maderna (nella foto, con Berio) è morto il 13 Novembre 1973 a soli 53 anni.

Il rivolgersi a oriente tipico della seconda metà degli anni ’60 coinvolge anche Stockhausen che, nel fatidico 1968, abbraccia con decisione le filosofie orientali. Passando attraverso Stimmung, giungerà gradualmente alla definizione di una musica intuitiva, praticamente priva di partitura

Il rivolgersi a oriente tipico della seconda metà degli anni ’60 coinvolge anche Stockhausen che, nel fatidico 1968, abbraccia con decisione le filosofie orientali. Passando attraverso Stimmung, giungerà gradualmente alla definizione di una musica intuitiva, praticamente priva di partitura Questo non significa che tutta l’opera, che dura ben 70 minuti, sia costituita da un unico accordo, ma quasi. Un accordo di 6 note implica una gamma di possibilità che va dalle singole note fino ad accordi composti di 2, 3, 4, 5 e finalmente 6 note. Inoltre, ogni nota può essere potenzialmente eseguita da più di un cantante (tutti dovrebbero poter cantare il RE).

Questo non significa che tutta l’opera, che dura ben 70 minuti, sia costituita da un unico accordo, ma quasi. Un accordo di 6 note implica una gamma di possibilità che va dalle singole note fino ad accordi composti di 2, 3, 4, 5 e finalmente 6 note. Inoltre, ogni nota può essere potenzialmente eseguita da più di un cantante (tutti dovrebbero poter cantare il RE).