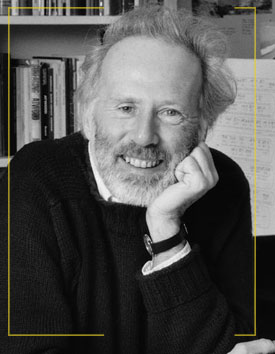

Steve Albini (qui su wikipedia in inglese e qui in italiano) è un musicista, produttore discografico, tecnico del suono e critico musicale americano. È una persona che conosce molto bene il mercato musicale; fra l’altro è stato produttore dei Nirvana.

Steve Albini (qui su wikipedia in inglese e qui in italiano) è un musicista, produttore discografico, tecnico del suono e critico musicale americano. È una persona che conosce molto bene il mercato musicale; fra l’altro è stato produttore dei Nirvana.

Nei primi anni ’90 ha scritto un articolo chiamato The Problem With Music in cui descrive la situazione di una band esordiente di un certo successo, come ne ha viste tante, che arriva a firmare il suo primo contratto con una major. Con la sua esperienza, Albini fa letteralmente i conti in tasca alla band, alla major, a produttori, manager e a molti personaggi che gravitano intorno al business musicale. È in articolo interessante anche perché, nonostante il fatto che circoli su internet ormai da 10 anni, non è stato mai direttamente smentito dalle major, evidentemente perché non sono in grado di farlo. D’altra parte le major si sono sempre sottratte alle discussioni sui loro margini di profitto (e su quelli di band, produttori, manager, etc.) adducendo il fatto che le situazioni sono troppo differenziate.

Ma, come ben sanno gli statistici, in economia le medie si possono sempre fare: basta riferirle a situazioni tipiche ed è quello che fa questo articolo.

Ho sempre voluto proporlo, ma finora sono stato trattenuto dal fatto che è in inglese-americano non proprio semplice e non ho mai avuto la voglia e il tempo di tradurlo (è piuttosto lungo). Oggi finalmente qualcuno lo ha fatto, quindi un plauso a LOR15, di cui vi segnalo il blog e da cui ho tratto la traduzione che riporto qui sotto e che mi sembra ben fatta.

Se a qualcuno interessa l’originale inglese, lo può leggere qui o qui, ma basta una ricerca in Google per trovarlo in molti siti.

È lungo, ma chiarisce molte cose. Se ne avete voglia e se vi interessa leggetelo, tanto per chiarire, fra l’altro, chi sono quelli che danno dei ladri ai ragazzini che si scaricano i CD.

Il problema con la musica

di Steve Albini

Ogni volta che parlo con una band che sta per firmare un contratto con una etichetta major, finisco sempre per pensare a loro in un contesto particolare. Immagino un fossato, largo un metro e venti, profondo un metro e cinquanta e forse lungo sei metri, pieno di merda. Immagino queste persone, alcune delle quali buoni amici, alcune semplici conoscenze, da una parte di questo fossato. Immagino pure un lacchè dell’industria, senza volto, dall’altra parte del fossato, con in mano una stilografica ed un contratto che aspetta di essere firmato. Nessuno può vedere cosa ci sia scritto nel contratto. È troppo lontano ed inoltre la puzza della merda fa lacrimare gli occhi di tutti. Il lacchè urla a tutti che il primo a nuotare attraverso il fossato firmerà il contratto. Tutti si buttano nel fossato e cercano furiosamente di arrivare dall’altra parte. Due persone arrivano nello stesso momento ed iniziano a lottare spingendosi reciprocamente la testa nella merda. Alla fine uno dei due capitola, e rimane un solo contendente. Allunga la mano verso la penna, ma il lacchè gli dice “credo che tu ti debba fare le ossa ancora un po’, nuota di nuovo, per favore. Questa volta a dorso”. E lui ovviamente lo fa.

I. A & R Scouts

Ogni etichetta major, coinvolta nella caccia di nuove bands, ha nello staff un uomo di alto profilo, un A&R che può presentare una faccia credibile ad ogni band con prospettive. Le iniziali stanno per “Artisti e Repertorio”, perché storicamente lo staff A&R seleziona gli artisti per registrare la musica che hanno anche scelto. Questo avviene ancora anche se non apertamente. Questi tipi sono generalmente giovani (la stessa età della band presa di mira) ed al giorno d’oggi hanno sempre qualche ovvia credibilità underground da mostrare. Lyle Preslar, ex chitarrista dei Minor Threat, è uno di loro. Terry Tolkin, ex organizzatore indipendente di concerti a NY e manager assistant della Touch And Go è uno di loro. Al Smith, ex ingegnere del suono del CBGB è uno di loro. Mike Bitter, ex editore della fanzine XXX e collaboratore di Rip, Kerrang ed altri, è uno di loro. Molti dei noiosi stronzi che riempivano le radio dei college sono nelle loro file.

Ci sono molte ragioni per cui gli A&R sono sempre giovani. La spiegazione solitamente usata è che è che lo scout deve essere “hip” per la scena musicale corrente. Un motivo più importante è che le bands intuitivamente avranno più fiducia in uno come loro e che parla con entusiasmo delle stesse esperienze formative rock and roll. L’ A&R è la prima persona ad avere contatto con la band, ed in quanto tale è il primo a promettere loro la luna. Chi meglio, per promettere loro la luna, di un tipo idealistico che si aspetta in pochi anni di fare carriera e che non ha esperienze precedenti con una grossa casa discografica. Cazzo, è un naive, un ingenuo, come la band che sta gabbando. Quando dice che nessuno interferirà nel loro processo creativo, probabilmente ci crede pure.

Quando si siede al tavolo con la band la prima volta, davanti ad un piatto di pasta, può dire loro in tutta sincerità, che quando firmeranno per la compagnia X, di fatto firmeranno per lui, e lui è dalla loro parte.Vi ricordate quel concerto a cui vi ho visto nel 1985? Non ci siamo divertiti un casino? Ora tutte le rock band sono diventate abbastanza sagge da essere sospettose della feccia dell’industria musicale. C’è una caricatura convincente nella cultura popolare di un ex-hipster di mezza età, corpulento, che parla velocissimo usando un gergo datato, chiamando tutti “baby”. Dopo avere incontrato il “loro” A&R, la band si dirà, e dirà a tutti, “non è per niente il classico tipo dell’industria discografica, è come uno di noi” E hanno ragione. Questo è proprio uno dei motivi per cui è stato incaricato.

A questi tipi A&R non è permesso di scrivere contratti. Quello che fanno è presentare alla band una lettera di intenti o un promemoria, che vagamente definisce alcuni termini ed afferma che la band firmerà con l’etichetta quando ci si sarà messi d’accordo sul contratto. La cosa più strana al riguardo di questo memo che sembra innocuo, è che, per tutti gli scopi legali, è un documento vincolante. Cioè, una volta che la band lo ha firmato, ha un obbligo di concludere l’affare con l’etichetta. Se l’etichetta presenta alla band un contratto che la band non vuole firmare, l’etichetta non ha che da aspettare. Ci sono centinaia di altre band che vogliono firmare lo stesso contratto, così l’etichetta è in una posizione di forza.

Queste lettere di intenti non hanno mai una data di scadenza, così la band rimane legata alla lettera di intenti, fino a quando il contratto viene firmato, non importa quanto ci si metterà. La band non può firmare con altri e non può pubblicare il proprio materiale a meno che l’accordo non venga annullato, cosa che non succede mai. Non sbagliatevi, una volta che una band ha firmato una lettera di intenti, o firmeranno un contratto che piace all’etichetta, o verranno distrutti. Una delle mie band favorite è stata tenuta ostaggio per almeno due anni da un furbo giovane “non è come uno di quelli delle etichette” sulla base di una tale lettera di intenti. Non rispettò alcuna delle promesse fatte (cosa che fece con effetto simile ad un’altra band ben conosciuta) e così la band voleva andarsene. Un’altra etichetta aveva manifestato interesse, ma quando all’A&R fu chiesto di liberare la band, disse che voleva denaro o punti percentuali, o possibilmente entrambi, prima di considerarlo. La nuova etichetta aveva paura che il prezzo fosse troppo caro, e disse di no. In procinto di fare l’album di esordio, una band eccellente, umiliata, per lo stress e per i molti mesi di inattività, si sciolse.

II. C’è questa band

C’è questa band. Non sono nulla di incredibile, ma sono anche abbastanza bravi, così hanno attirato un po’ di attenzione. Hanno firmato per una etichetta “indipendente” media, proprietà di una compagnia di distribuzione, e devono ancora due album alla etichetta. Vorrebbero firmare per una major, così potrebbero avere delle sicurezze, sapete, avere dei buoni strumenti, fare i tour in un bus decente, niente fronzoli, solo una piccola ricompensa per il loro duro lavoro. A quel punto hanno un manager. Conosce un po’ di gente delle etichette e potrebbe vendere il loro prossimo progetto alla gente giusta. Lui prende la sua percentuale, ma è solo il 15%, e se fa loro firmare un contratto, allora è denaro ben speso. In ogni caso a loro non costa nulla, se non funziona. Il 15% di niente non è molto!

Un giorno uno scout A&R li chiama, dice che li sta seguendo da un po’ e che quando il loro manager gli ha fatto il loro nome, ha fatto subito “click”. Perché non incontrarsi per parlare della possibilità di un contratto con la sua etichetta? Wow. È il momento di sfondare. Incontrano il tipo, e sapete cosa – non è quello che si sarebbero aspettati da un tipo di una etichetta. È giovane ed è vestito più o meno come la band. Conosce tutte le loro band preferite. È uno di loro. Dice che vuole provare a fare ottenere loro tutto quello che vogliono. Dice che tutto è possibile con l’atteggiamento giusto. Concludono la serata portando a casa una lettera di intenti, scritta e firmata al momento.

Il tipo A&R era pieno di grandi idee, ha parlato anche di usare un produttore di grido. Butch Vig è fuori discussione, pretende 100.000 dollari e tre punti percentuali, ma possono avere Don Fleming per 30.000 $ e tre punti percentuali. Se anche quello è un po’ troppo allora possono avere quel tipo che era nella band di David Letterman. Vuole solo i tre punti. O possono scegliere chi vogliono (tipo Warton Tiers forse, costa solo 5 o 7mila dolalri) e prendere Andy Fallace per remixare per 4mila a traccia più 2 punti. C’era molto a cui pensare.

Bene, a loro piace questo tipo ed hanno fiducia in lui. Inoltre hanno già firmato la lettera di intenti. Lui doveva avere intenzioni serie per voler firmare un contratto. Danno notizia alla loro etichetta attuale, ed il manager dice che vuole che abbiano successo, così hanno la sua benedizione. Lui ovviamente dovrà essere compensato, per gli album in contratto ancora da fare, ma lui stesso chiarirà tutto con la nuova etichetta. La Sub Pop ha fatto milioni vendendo i Nirvana e la Twin Tone non ha fatto male anche lei: 50mila per le Babes e 60 mila per i Poster Children – senza dover vendere un solo disco in più. Sarà qualcosa di modesto. Alla nuova etichetta non importa il prezzo, fin quando è recuperabile dalle royalties. Bene, ricevono il contratto finale e non è quello che si aspettavano. Immaginano che sia meglio andare sul sicuro e lo fanno vedere ad un avvocato, uno che dice di essere esperto di contratti del mondo dello spettacolo e lui trova qualche errore da correggere. Loro non sono ancora convinti, ma l’avvocato dice che ha visto molti contratti e che questo è piuttosto buono. Avranno molte royalties: 13% (meno 10% di deduzione packaging).Non erano i Buffalo Tom che prendevano solo 12% meno il 10%). Fa lo stesso.

La vecchia etichetta vuole solo 50mila e nessun punto percentuale. Cazzo, la Sub Pop prese 3 punti quando lasciò andare i Nirvana. Hanno firmato per 4 anni, con opzione per ogni anno, per più di un milione di dollari! Solo l’anticipo per il primo anno è di 250mila $. Pensateci un attimo, un quarto di milione solo per essere una rock band!

Il loro manager pensa che sia un grande affare specialmente per il grosso anticipo. Inoltre, lui conosce una casa di pubblicazioni che prenderà la band se avranno un contratto e anche questi daranno loro un anticipo di 20mila, così incasseranno anche questi soldi. Il manager dice che il settore del publishing è piuttosto misterioso e nessuno sa bene da dove arrivi il denaro, ma l’avvocato può dare uno sguardo al contratto. Cazzo, sono soldi regalati.

Il loro booking agent è eccitato per il fatto che firmino per una major. Dice che possono incassare in media 1.000 o 2000 $ a sera da ora in poi. È abbastanza per giustificare un tour di cinque giorni la settimana e con una band di supporto, possono usare un vera crew, comprare degli strumenti adeguati ed avere addirittura un tour bus! I bus sono piuttosto costosi, ma se pensate al costo delle stanze d’albergo per tutta la band e la crew, è più o meno lo stesso costo. Alcune band come Therapy?, Sloan e Stereolab usano i bus in tour anche quando vengono pagati poche centinaia di dollari a notte e questo tour deve incassare almeno 1.000 e 2.000 dollari a notte. Ne varrà la pena. La band sarà più a suo agio e suonerà meglio. L’agente dice che una band su una etichetta major può farsi pagare un anticipo da una società di merchandising sulle vendite delle t-shirts! Ridicolo! È una miniera d’oro! Che l’avvocato dia una letta anche al contratto di merchandising, giusto per andare sul sicuro.

Si ubriacano al party per la firma del contratto. Vengono scattate polaroids e tutti sono eccitati. L’etichetta è andata a prenderli con una limousine. Decidono di usare il produttore che era nella band di Letterman. Il tipo porta dei tecnici per accordare la batteria per loro e regolare amplificatori e chitarre. Ha pure fatto portare dei microfoni vintage. Ragazzi, come erano “caldi”. Ha portato pure un tipo per controllare le fasi di tutto l’equipaggiamento nella sala di controllo. Ragazzi, che professionista. Ha usato un po’ di equipaggiamento e alla fine erano tutti d’accordo che tutto suonava molto “punchy” e “caldo”.

Tutto quel duro lavoro finalmente ha dato i suoi frutti. Con l’aiuto di un video, l’album è stato venduto come panini caldi. Hanno venduto 250mila copie! Di seguito i conti che spiegano quanto siano fottuti: Questi numeri sono rappresentativi di importi che appaiono quotidianamente in contratti discografici. Non c’è bisogno di manipolare i numeri per fare apparire male lo scenario, dal momento che gli esempi veri abbondano.

| Anticipo |

$ 250.000 |

|

|

|

|

| Percentuale del Manager |

$ 37,500 |

| Avvocati |

$ 10,000 |

|

|

|

|

| Recording Budget |

$ 150,000 |

| Anticipo produttore |

$ 50,000 |

| Spese Studio |

$ 52,500 |

| Drum. Amp, Mic and Phase “Doctors” |

$ 3,000 |

| Nastro per la registrazione |

$ 8,000 |

| Affitto attrezzature |

$ 5,000 |

| Trasporti |

$ 5,000 |

| Pernottamenti durante lavoro in studio |

$ 10,000 |

| Catering |

$ 3,000 |

| Mastering |

$ 10,000 |

| Copie su nastro, reference CDs, spedizione nastri, spese varie |

$ 2,000 |

|

|

|

|

| Video budget |

$ 30,000 |

| telecamere |

$ 8,000 |

| Crew |

$ 5,000 |

| Processing e riversamenti |

$ 3,000 |

| Off-line |

$ 2,000 |

| On-line editing |

$ 3,000 |

| Catering |

$ 1,000 |

| Palco e costruzioni |

$ 3,000 |

| Copie, corrieri, trasporti |

$ 2,000 |

| Costi del Director |

$ 3,000 |

|

|

|

|

| Album Artwork |

$ 5,000 |

| Foto promozionali e copie |

$ 2,000 |

| Fondo Band |

$ 15,000 |

| Nuova batteria professionale |

$ 5,000 |

| Nuove chitarre professionali[2] |

$ 3,000 |

| Nuovi ampli chitarra professionali [2] |

$ 4,000 |

| Basso a forma di patata |

$ 1,000 |

| Nuovo ampli per basso con lucette |

$ 1,000 |

| Affitto sala prove |

$ 500 |

|

|

|

|

| Gran party per gli amici |

$ 500 |

|

|

|

|

| Tour spese [5 settimane] |

$ 50,875 |

| Bus |

$ 25,000 |

| Crew [3] |

$ 7,500 |

| Cibo e per diems |

$ 7,875 |

| Carburante |

$ 3,000 |

| Beni di consumo |

$ 3,500 |

| Guardaroba |

$ 1,000 |

| Promotion |

$ 3,000 |

|

|

|

|

| Guadagno lordo del tour |

$ 50,000 |

| Percentuale Agente |

$ 7,500 |

| Percentuale Manager |

$ 7,500 |

|

|

|

|

| Merchandising anticipo |

$ 20,000 |

| Percentuale Manager |

$ 3,000 |

| Parcella Avvocato |

$ 1,000 |

|

|

|

|

| Anticipo pubblicazione |

$ 20,000 |

| Percentuale Manager |

$ 3,000 |

| Parcella Avvocato |

$ 1,000 |

|

|

|

|

| Vendita dischi 250,000 copie a $12 = |

$3,000,000 |

| Royalty di vendita all’ingrosso [13% del 90% del dettaglio] |

$ 351,000 |

| A detrazione anticipo |

$ 250,000 |

| Percentuale produttore [3% meno $50,000 di anticipo] |

$ 40,000 |

| Budget promozionale |

$ 25,000 |

| Penale etichetta precedente |

$ 50,000 |

| Royalty nette |

$ -14,000 |

|

|

|

|

| Entrate etichetta discografica |

|

| Vendita dischi (entrata lorda) $6.50 x 250,000 = |

$1,625,000 |

| Royalties Artisti |

$ 351,000 |

| Deficit dalle royalties |

$ 14,000 |

| Produzione, packaging e distribuzione @ $2.20 a disco |

$ 550,000 |

| Profitto lordo |

$ 7l0,000 |

|

|

|

|

Il bilancio:

|

|

| questo è quanto ogni giocatore è stato pagato alla fine di questo gioco |

|

|

|

| Casa discografica |

$ 710,000 |

| Produttore |

$ 90,000 |

| Manager |

$ 51,000 |

| Studio |

$ 52,500 |

| Etichetta precedente |

$ 50,000 |

| Agente |

$ 7,500 |

| Avvocato |

$ 12,000 |

| Entrate nette per ogni membro band |

$ 4,031.25 |

La band è ora ad un quarto del proprio percorso contrattuale, ha arricchito l’industria discografica di più di 3 milioni di dollari ma è in perdita di 14.000 sulle royalties. I membri della band hanno guadagnato 1/3 di quello che avrebbero guadagnato lavorando da 7eleven (catena di supermercati NdT) ma hanno dovuto girare in un bus per un mese.

Il prossimo album sarà la stessa cosa con la differenza che l’etichetta insisterà che spendano più soldi su di esso. Da momento che il precedente non ha mai “recuperato” le spese, la band non si può opporre.

Il prossimo tour ancora sarà la stessa cosa, a parte il fatto che l’anticipo per il merchandising sarà già stato pagato, e la band, piuttosto stranamente, non avrà guadagnato alcune royalties dalla vendita delle magliette. Probabilmente i tipi della vendita delle magliette avranno imparato a contare i soldi come i tipi della casa discografica.

Alcuni dei vostri amici probabilmente sono già fottuti a tal punto.

R. Murray Schafer – Snowforms (1982) – for treble choir

R. Murray Schafer – Snowforms (1982) – for treble choir

Un album fatto di sottili rumori e sonorità nostalgiche e degradate questo di Gutta Percha, due fratelli (Brent & Ryan Hibbett) dall’Illinois, l’uno poli-strumentista, l’altro sound architect.

Un album fatto di sottili rumori e sonorità nostalgiche e degradate questo di Gutta Percha, due fratelli (Brent & Ryan Hibbett) dall’Illinois, l’uno poli-strumentista, l’altro sound architect.

The idea for “Folds And Rhizomes” came as a result of contact that was made between the Sub Rosa label and Deleuze himself.

The idea for “Folds And Rhizomes” came as a result of contact that was made between the Sub Rosa label and Deleuze himself.

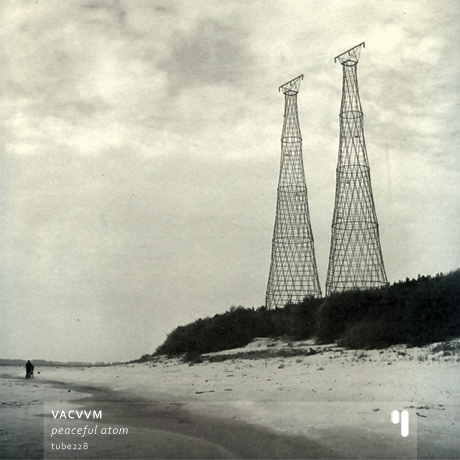

The Beam Drop

The Beam Drop When it was born in the mind of italian musician Guglielmo Cherchi (aka VACVVM), ‘Peaceful Atom’ was intended to be a concept work about the Chernobyl disaster, and as a result of this some tracks are ideally connected to that topic: the title track (referring to the name of the first RBMK – Reactor Bolshoy Moshchnosty Kanalny – reactor), SCRAM (the emergency shutdown of a nuclear reactor), Lava Flow (the melted material erupted from the reactor after the explosion), Leaving Pripyat (the evacuation of the nearest city to the powerplant), Worm Wood Forest (the dead trees killed by the radiations) and Ignalina’s Sunset (Ignalina was the last nuclear powerplant to use a RBMK reactor, the same model involved in the Chernobyl disaster, which was only shut down in 2009).

When it was born in the mind of italian musician Guglielmo Cherchi (aka VACVVM), ‘Peaceful Atom’ was intended to be a concept work about the Chernobyl disaster, and as a result of this some tracks are ideally connected to that topic: the title track (referring to the name of the first RBMK – Reactor Bolshoy Moshchnosty Kanalny – reactor), SCRAM (the emergency shutdown of a nuclear reactor), Lava Flow (the melted material erupted from the reactor after the explosion), Leaving Pripyat (the evacuation of the nearest city to the powerplant), Worm Wood Forest (the dead trees killed by the radiations) and Ignalina’s Sunset (Ignalina was the last nuclear powerplant to use a RBMK reactor, the same model involved in the Chernobyl disaster, which was only shut down in 2009). I rumeni Felix Petrescu (Waka X) e Valentin Toma (Qewza), nel 2001 hanno dato vita a questo progetto sperimentale chiamato Makunouchi Bento (che è il nome di un pranzo “al sacco” giapponese).

I rumeni Felix Petrescu (Waka X) e Valentin Toma (Qewza), nel 2001 hanno dato vita a questo progetto sperimentale chiamato Makunouchi Bento (che è il nome di un pranzo “al sacco” giapponese).

Dal fascinoso Zodiac, del percussionista inglese

Dal fascinoso Zodiac, del percussionista inglese  Potete scaricare

Potete scaricare

La

La  Il

Il  Non tutti sanno che John Carpenter, regista di pellicole tendenzialmente horror come Halloween, la notte delle streghe (1978), 1997: fuga da New York (1981), La cosa (1982), Il signore del male (1987), Essi vivono (1988), Il seme della follia (1994), Villaggio dei dannati (1995), Fuga da Los Angeles (1996), Vampires (1998), Fantasmi da Marte (2001), scrive e registra anche molte delle colonne sonore dei suoi film (date un’occhiata anche al

Non tutti sanno che John Carpenter, regista di pellicole tendenzialmente horror come Halloween, la notte delle streghe (1978), 1997: fuga da New York (1981), La cosa (1982), Il signore del male (1987), Essi vivono (1988), Il seme della follia (1994), Villaggio dei dannati (1995), Fuga da Los Angeles (1996), Vampires (1998), Fantasmi da Marte (2001), scrive e registra anche molte delle colonne sonore dei suoi film (date un’occhiata anche al

Ieri mi sono ritrovato a canticchiare una canzone che a un certo punto diceva

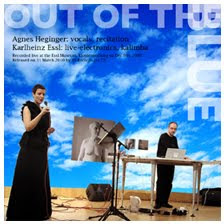

Ieri mi sono ritrovato a canticchiare una canzone che a un certo punto diceva Agnes Heginger, soprano e Karlheinz Essl, elettronico, hanno registrato poco meno di un anno fa, all’Essl Museum in Vienna, questo disco, dal titolo Out of the Blue.

Agnes Heginger, soprano e Karlheinz Essl, elettronico, hanno registrato poco meno di un anno fa, all’Essl Museum in Vienna, questo disco, dal titolo Out of the Blue.

Strutture abbandonate sono quelle che vengono alla mente ascoltando questa release per Test Tube di Philip Croaton, russo, così come viene in mente Tarkovsky.

Strutture abbandonate sono quelle che vengono alla mente ascoltando questa release per Test Tube di Philip Croaton, russo, così come viene in mente Tarkovsky.

Il libro di

Il libro di  ), uno di amusia cocleare (deviazione nella percezione dell’altezza dei suoni che affligge un compositore: idem) e il sorprendente capitolo dedicato a un medico che, dopo essere stato colpito da un fulmine, sviluppa un insaziabile desiderio di ascoltare musica per pianoforte, suonare e perfino comporre, si passano ore piacevoli a riflettere sulla complessità di quel sistema percettivo il cui funzionamento è in massima parte determinato dalla comunicazione bilaterale orecchie -> cervello che alla fine dà vita al fenomeno musicale.

), uno di amusia cocleare (deviazione nella percezione dell’altezza dei suoni che affligge un compositore: idem) e il sorprendente capitolo dedicato a un medico che, dopo essere stato colpito da un fulmine, sviluppa un insaziabile desiderio di ascoltare musica per pianoforte, suonare e perfino comporre, si passano ore piacevoli a riflettere sulla complessità di quel sistema percettivo il cui funzionamento è in massima parte determinato dalla comunicazione bilaterale orecchie -> cervello che alla fine dà vita al fenomeno musicale.

The Side Effect is a swedish trio composed by Dan Pålsson

The Side Effect is a swedish trio composed by Dan Pålsson

The

The

Matt’s (aka Craque) electronic music came to be regarded as a hybrid between edgy improv takes and deep IDM-ish grooves. Both languages come together through Matt’s electronics and form an intricate and complex maze of rhythms, beats and hypnotic grooves.

Matt’s (aka Craque) electronic music came to be regarded as a hybrid between edgy improv takes and deep IDM-ish grooves. Both languages come together through Matt’s electronics and form an intricate and complex maze of rhythms, beats and hypnotic grooves. «Brian Ruskin is a Ph.D in Geology (Stratigraphy branch) and at the same time a musician and producer from Pittsburgh, USA. Science and Art very close together. The music he makes as Mental Health Consumer falls right in the middle of the Electronic genre, slightly danceable and upbeat variant, without loosing too much focus but admittedly keen on experimental ambient explorations. With his music, Brian tries to achieve that special balance between the calculated and the emotive side of the mind.

«Brian Ruskin is a Ph.D in Geology (Stratigraphy branch) and at the same time a musician and producer from Pittsburgh, USA. Science and Art very close together. The music he makes as Mental Health Consumer falls right in the middle of the Electronic genre, slightly danceable and upbeat variant, without loosing too much focus but admittedly keen on experimental ambient explorations. With his music, Brian tries to achieve that special balance between the calculated and the emotive side of the mind. Justin Robert and Jeremy Powell are both enthusiast musicians that play live jazz for a living. Justin is a percussionist and likes to fiddle with analog synths, and Jeremy plays saxophone.

Justin Robert and Jeremy Powell are both enthusiast musicians that play live jazz for a living. Justin is a percussionist and likes to fiddle with analog synths, and Jeremy plays saxophone.

ToBeContinued…

ToBeContinued… The Drawing Center

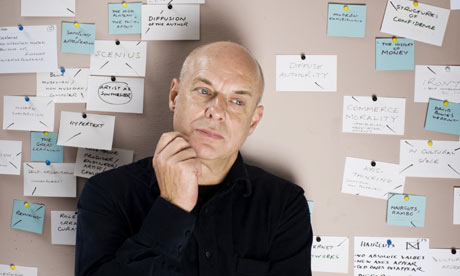

The Drawing Center Paul Morley recently spoke to Brian Eno for a BBC arena documentary in which Eno proved that he is always good for a controversial and catchy phrase about the music industry:

Paul Morley recently spoke to Brian Eno for a BBC arena documentary in which Eno proved that he is always good for a controversial and catchy phrase about the music industry: The sound of Akashic Crow’s Nest begins with the use of an image synthesizer which turns very long photographic images into audio output, in the manner of a piano roll. The initial part of composing this music is thus designing the picture. For this latest project, the first audio output is converted to midi and run through a different softsynth, before being subjected to a battery of effects to get to the sounds you hear on this album.

The sound of Akashic Crow’s Nest begins with the use of an image synthesizer which turns very long photographic images into audio output, in the manner of a piano roll. The initial part of composing this music is thus designing the picture. For this latest project, the first audio output is converted to midi and run through a different softsynth, before being subjected to a battery of effects to get to the sounds you hear on this album.

A Million Billion is Ryan Smith based out of Queens, NYC. ‘Cavity Care’ is a collection of compositions that Ryan wrote in collaboration with several choreographers over the last 6 years.

A Million Billion is Ryan Smith based out of Queens, NYC. ‘Cavity Care’ is a collection of compositions that Ryan wrote in collaboration with several choreographers over the last 6 years. I like the rhythmic feeling of this work. Rhythm is the main stream around which all the sound moves. Rich rhythmic patterns that derivate from dub, hip hop, techno and other urban languages, but instead of driving us straight to the physical emotion center, they drive us to the ‘braindance’ center.

I like the rhythmic feeling of this work. Rhythm is the main stream around which all the sound moves. Rich rhythmic patterns that derivate from dub, hip hop, techno and other urban languages, but instead of driving us straight to the physical emotion center, they drive us to the ‘braindance’ center. Umbrellas in the Rain is the alias of an austrian musician from Vienna, and ‘Wieder Daheim’ – german for ‘Home Again’ – his first effort at creating something mature enough worth listening to (and worth releasing, for that matter…). Well, he did it, and with flying colours. ‘Wieder Daheim’ is a delicate collection of abstract songs that really grab one’s heart. They are experimental enough to wander in, but also emotional enough – to the point of being nostalgic – to keep us down to earth.

Umbrellas in the Rain is the alias of an austrian musician from Vienna, and ‘Wieder Daheim’ – german for ‘Home Again’ – his first effort at creating something mature enough worth listening to (and worth releasing, for that matter…). Well, he did it, and with flying colours. ‘Wieder Daheim’ is a delicate collection of abstract songs that really grab one’s heart. They are experimental enough to wander in, but also emotional enough – to the point of being nostalgic – to keep us down to earth.

Bloom, Trope and Air are three applications developed by Brian Eno and the musician / software designer Peter Chilvers that brings to the iPhone the concept of generative music popularized by Eno.

Bloom, Trope and Air are three applications developed by Brian Eno and the musician / software designer Peter Chilvers that brings to the iPhone the concept of generative music popularized by Eno.

In the August and September 1977, two Voyager spacecraft were launched to fly by and explore the great gaseous planets of Jupiter and Saturn.

In the August and September 1977, two Voyager spacecraft were launched to fly by and explore the great gaseous planets of Jupiter and Saturn. Non c’è niente come rimettere in ordine una casa che contiene, fra l’altro, varie migliaia di dischi (CD e vinili) sparsi fra diversi mobili, per ritrovare cose che non ricordavi di avere. Orologi russi, vecchie foto in cui fai fatica a capire chi c’è e anche qualche disco che non ascoltavi da una vita.

Non c’è niente come rimettere in ordine una casa che contiene, fra l’altro, varie migliaia di dischi (CD e vinili) sparsi fra diversi mobili, per ritrovare cose che non ricordavi di avere. Orologi russi, vecchie foto in cui fai fatica a capire chi c’è e anche qualche disco che non ascoltavi da una vita.

Sacred flutes are blown (“Windim Mambu”) to make the cries of spirits by adult men in the Madang region of Papua New Guinea. Pairs of long bamboo male and female flutes are played for ceremonies in the coastal villages near the Ramu River

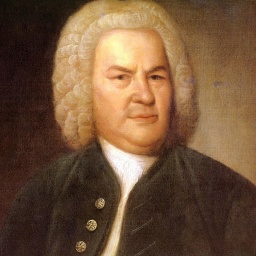

Sacred flutes are blown (“Windim Mambu”) to make the cries of spirits by adult men in the Madang region of Papua New Guinea. Pairs of long bamboo male and female flutes are played for ceremonies in the coastal villages near the Ramu River Sentite un po’ Pierre-Laurent Aimard che suona Bach, nientemeno che l’Arte della Fuga.

Sentite un po’ Pierre-Laurent Aimard che suona Bach, nientemeno che l’Arte della Fuga.

Un po’ di sana aggressione sonora in stile post free jazz europeo non fa mai male. Dalla netlabel Insubordinations, l’ultimo lavoro del gruppo svizzero

Un po’ di sana aggressione sonora in stile post free jazz europeo non fa mai male. Dalla netlabel Insubordinations, l’ultimo lavoro del gruppo svizzero  “Music,” says Toshio Hosokawa, “is the place where notes and silence meet.” This identifies his aesthetic concept as a genuinely Japanese one. It is found both in Japanese landscape painting and in the music, such as the courtly gagaku, in which audible sound always stands in relation to nonsound, i.e. to silence. In their rhythmic proportions Hosokawa’s compositions are oriented around the breathing methods of Zen meditation, with their very slow breathing in and very slow breathing out: “Each breath contains life and death, death and life.”

“Music,” says Toshio Hosokawa, “is the place where notes and silence meet.” This identifies his aesthetic concept as a genuinely Japanese one. It is found both in Japanese landscape painting and in the music, such as the courtly gagaku, in which audible sound always stands in relation to nonsound, i.e. to silence. In their rhythmic proportions Hosokawa’s compositions are oriented around the breathing methods of Zen meditation, with their very slow breathing in and very slow breathing out: “Each breath contains life and death, death and life.”

Nanimo nai wakusei means “empty planets” in Japanese and is an apt description for key elements of Tim Salden’s music as Osoroshisa. It reflects the width of uninhabited and lonesome worlds and how time becomes a secondary factor on an empty planet that lacks any point of reference for perceiving its continuous passage. In the broader sense, it may also refer to isolated persons living in a solar system of their own, without a way of taking notice of other worlds apart from theirs and where chains of events have gradually been replaced by a constant train of thoughts. Accordingly, the music is located between drone and dark ambient without being particularly representative of either genre and evolves slowly, with recurrent figures weaved into persistent drones and subtle changes in modulation rather than thematic variation and progression.

Nanimo nai wakusei means “empty planets” in Japanese and is an apt description for key elements of Tim Salden’s music as Osoroshisa. It reflects the width of uninhabited and lonesome worlds and how time becomes a secondary factor on an empty planet that lacks any point of reference for perceiving its continuous passage. In the broader sense, it may also refer to isolated persons living in a solar system of their own, without a way of taking notice of other worlds apart from theirs and where chains of events have gradually been replaced by a constant train of thoughts. Accordingly, the music is located between drone and dark ambient without being particularly representative of either genre and evolves slowly, with recurrent figures weaved into persistent drones and subtle changes in modulation rather than thematic variation and progression.

Negli anni ’70, Cornelius Cardew, fino ad allora uno dei più importanti compositori inglesi, pioniere dell’utilizzo di partiture grafiche e dell’improvvisazione, assistente di Stockhausen dal 1958 al 1960, ebbe una improvvisa conversione politica al Comunismo (per la precisione aderì al

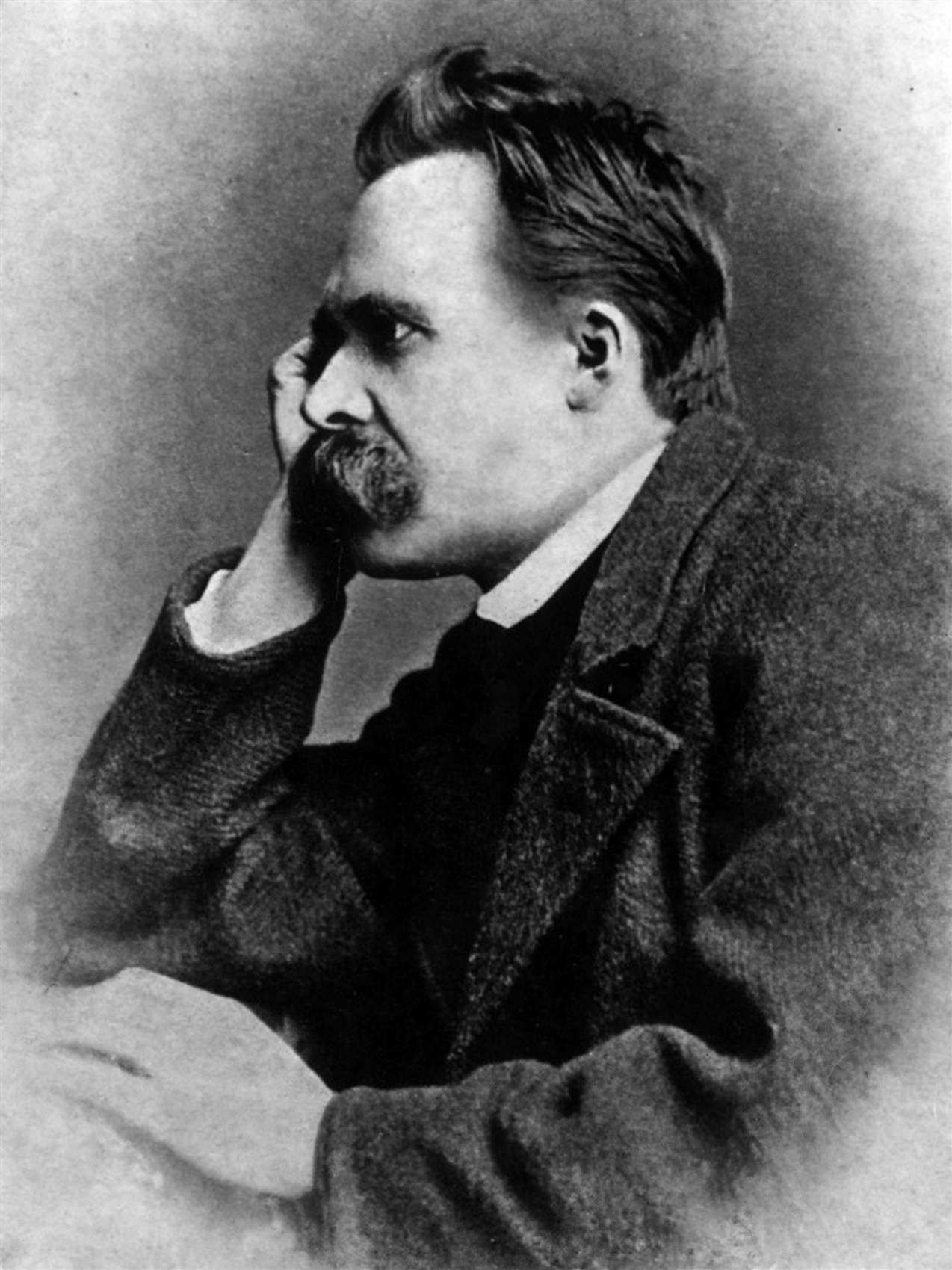

Negli anni ’70, Cornelius Cardew, fino ad allora uno dei più importanti compositori inglesi, pioniere dell’utilizzo di partiture grafiche e dell’improvvisazione, assistente di Stockhausen dal 1958 al 1960, ebbe una improvvisa conversione politica al Comunismo (per la precisione aderì al  Il Fragment an Sich (Frammento in sè) è un brano per pianoforte solo, scritto dal filosofo Friedrich Nietzsche, datato Ottobre 1871.

Il Fragment an Sich (Frammento in sè) è un brano per pianoforte solo, scritto dal filosofo Friedrich Nietzsche, datato Ottobre 1871.

Il chitarrista Les Paul (il cui vero nome era Lester William Polsfuss), inventore della chitarra solid-body e curatore della linea di strumenti Gibson che porta il suo nome, si è spento ieri a White Plains (NY) alla veneranda età di 94 anni.

Il chitarrista Les Paul (il cui vero nome era Lester William Polsfuss), inventore della chitarra solid-body e curatore della linea di strumenti Gibson che porta il suo nome, si è spento ieri a White Plains (NY) alla veneranda età di 94 anni. Era tempo che qualcuno diffondesse una nuova versione di alcuni brani del ciclo

Era tempo che qualcuno diffondesse una nuova versione di alcuni brani del ciclo

Se qualcuno ha bisogno di un dado a 12 facce con le note sopra può

Se qualcuno ha bisogno di un dado a 12 facce con le note sopra può  Let’s go back to 2006.

Let’s go back to 2006. Sylvie Walder and entia non (James McDougall) are well-known names in the netlabel-world and beyond. Sylvie Walder released collaboration-albums with Phillip Wilkerson, Siegmar Fricke, and “_” (as Kakitsubata). entia non has released solo-works on test tube, IOD, u-cover, Resting Bell and contributions on compilations for duckbay and Slow Flow Recs.

Sylvie Walder and entia non (James McDougall) are well-known names in the netlabel-world and beyond. Sylvie Walder released collaboration-albums with Phillip Wilkerson, Siegmar Fricke, and “_” (as Kakitsubata). entia non has released solo-works on test tube, IOD, u-cover, Resting Bell and contributions on compilations for duckbay and Slow Flow Recs.

The new album by

The new album by  Matúš Mikula, aka 900piesek, è slovacco, uno dei giovani musicisti elettroacustici europei che creano una sorta di science fiction ambient con un po’ di nostalgia degli anni ’70.

Matúš Mikula, aka 900piesek, è slovacco, uno dei giovani musicisti elettroacustici europei che creano una sorta di science fiction ambient con un po’ di nostalgia degli anni ’70. Non è un errore di stampa.

Non è un errore di stampa.

Laurent Peter è un musicista svizzero (Ginevra) più noto come

Laurent Peter è un musicista svizzero (Ginevra) più noto come  Octandre è rappresentativo di un modo di comporre tipico di Edgar Varèse, sviluppando e variando piccoli frammenti sonori. Lo stesso compositore lo descrive mediante una analogia con la crescita di un cristallo.

Octandre è rappresentativo di un modo di comporre tipico di Edgar Varèse, sviluppando e variando piccoli frammenti sonori. Lo stesso compositore lo descrive mediante una analogia con la crescita di un cristallo.

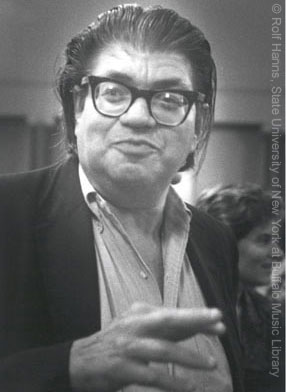

…consiste nel fatto che un uomo corpulento, gioviale e ciarliero si metta a scrivere della musica ai limiti dell’udibile. In un secolo rumoroso come il nostro, Morton Feldman ha scelto di essere silenzioso e soffice come la neve.

…consiste nel fatto che un uomo corpulento, gioviale e ciarliero si metta a scrivere della musica ai limiti dell’udibile. In un secolo rumoroso come il nostro, Morton Feldman ha scelto di essere silenzioso e soffice come la neve.

Philippe Manoury

Philippe Manoury Ok, un po’ di tranquillità dopo lo sforzo organizzativo del Premio Nazionale delle Arti.

Ok, un po’ di tranquillità dopo lo sforzo organizzativo del Premio Nazionale delle Arti.

Attivi dalla fine degli anni ’60, i

Attivi dalla fine degli anni ’60, i

Un impressionante brano del chitarrista e improvvisatore

Un impressionante brano del chitarrista e improvvisatore

Keith Rowe, forse il prototipo dei chitarristi improvvisatori di scuola anglosassone, esegue un brano di Cornelius Cardew tratto dall’album “A Dimension of Perfectly Ordinary Reality” del 1990.

Keith Rowe, forse il prototipo dei chitarristi improvvisatori di scuola anglosassone, esegue un brano di Cornelius Cardew tratto dall’album “A Dimension of Perfectly Ordinary Reality” del 1990. Brian Eno’s

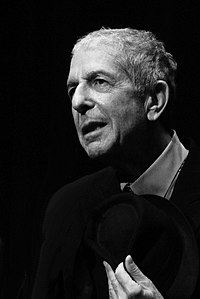

Brian Eno’s  Il poeta e cantautore canadese

Il poeta e cantautore canadese  This is one of those releases that floods me with metaphorical insights.

This is one of those releases that floods me with metaphorical insights.

Nuova, nostalgica release da test tube.

Nuova, nostalgica release da test tube.

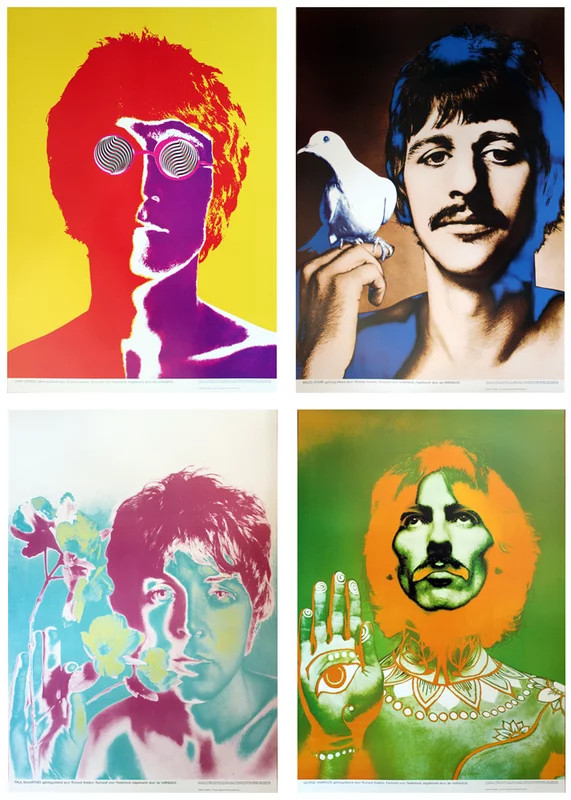

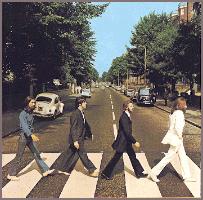

In questo video di Blame Ringo, la gente cammine sulle zebre in Abbey Road ricreando il famoso attraversamento dei Beatles impresso sulla copertina dell’omonimo album, uno dei più belli e ricercati dell’intera storia del pop. La canzoncina di Blame Ringo sarà anche simpatica, ma mi fa sentire quanto tempo è passato.

In questo video di Blame Ringo, la gente cammine sulle zebre in Abbey Road ricreando il famoso attraversamento dei Beatles impresso sulla copertina dell’omonimo album, uno dei più belli e ricercati dell’intera storia del pop. La canzoncina di Blame Ringo sarà anche simpatica, ma mi fa sentire quanto tempo è passato. Alcuni dei drones di Kalte, duo canadese, sono decisamente accattivanti. Qualcuno può dire che sono soltanto drones, ma si tratta di un genere che mi affascina e che non è così facile come sembra.

Alcuni dei drones di Kalte, duo canadese, sono decisamente accattivanti. Qualcuno può dire che sono soltanto drones, ma si tratta di un genere che mi affascina e che non è così facile come sembra. Iain David McGeachy, meglio noto come John Martyn è morto in Irlanda all’età di 60 anni. Nato nel 1948, nel Surrey (Inghilterra), era cresciuto a Glasgow (Scozia), dove, a 19 anni, aveva cominciato a farsi conoscere per il suo stile caratterizzato da una miscela di blues e folk.

Iain David McGeachy, meglio noto come John Martyn è morto in Irlanda all’età di 60 anni. Nato nel 1948, nel Surrey (Inghilterra), era cresciuto a Glasgow (Scozia), dove, a 19 anni, aveva cominciato a farsi conoscere per il suo stile caratterizzato da una miscela di blues e folk.

Searching the old releases from

Searching the old releases from  Qualche novità dalla netlabel

Qualche novità dalla netlabel

YouTube è pieno di sorprese. Per un post-natale alquanto melenso eccovi una clip di 30 anni fa: 1977, David Bowie e Bing Crosby cantano in duo The Little Drummer Boy, una canzone natalizia americana della peggior specie che parla di

YouTube è pieno di sorprese. Per un post-natale alquanto melenso eccovi una clip di 30 anni fa: 1977, David Bowie e Bing Crosby cantano in duo The Little Drummer Boy, una canzone natalizia americana della peggior specie che parla di Doctor Octoroc rilascia un album composto da revisioni di carole natalizie arrangiate nel classico stile 8-bit dei vecchi videogames. Il tutto è

Doctor Octoroc rilascia un album composto da revisioni di carole natalizie arrangiate nel classico stile 8-bit dei vecchi videogames. Il tutto è

Un altro lavoro di Lezrod (aka David Velez) pubblicato, come al solito da test tube. Questa volta si tratta di 10 pezzi che accompagnano altrettanti video da proiettare in un sushi bar a Las Vegas. Il tutto con il significativo titolo di fear and loathing in rio/tokyo (paura e disgusto in rio/tokyo).

Un altro lavoro di Lezrod (aka David Velez) pubblicato, come al solito da test tube. Questa volta si tratta di 10 pezzi che accompagnano altrettanti video da proiettare in un sushi bar a Las Vegas. Il tutto con il significativo titolo di fear and loathing in rio/tokyo (paura e disgusto in rio/tokyo).

Ylem è un termine usato da

Ylem è un termine usato da

In questo progetto della netlabel

In questo progetto della netlabel  20’51” è il nuovo lavoro del compositore colombiano, trasferito a NY,

20’51” è il nuovo lavoro del compositore colombiano, trasferito a NY,  Tripla maledizione, scrivere necrologi è deprimente.

Tripla maledizione, scrivere necrologi è deprimente. Steve Albini (

Steve Albini (

Normalmente non mi occupo di jazz, però, come giustamente fa notare wikipedia, definire

Normalmente non mi occupo di jazz, però, come giustamente fa notare wikipedia, definire

No, non si tratta della sonata 29 op. 106 di Ludwig Van, ma di un recente lavoro elettroacustico di

No, non si tratta della sonata 29 op. 106 di Ludwig Van, ma di un recente lavoro elettroacustico di

Un po’ di free jazz condito con elettronica non fa mai male.

Un po’ di free jazz condito con elettronica non fa mai male.

Uno dei desideri di

Uno dei desideri di

Bellissimo e spiazzante è ciò che il compositore dice del silenzio, che abbonda in quest’opera:

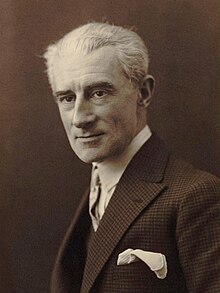

Bellissimo e spiazzante è ciò che il compositore dice del silenzio, che abbonda in quest’opera: Ipotesi recenti suggeriscono che Maurice Ravel, il cui decesso è imputato ad una non ben identificata atrofia cerebrale o all’Alzheimer, soffrisse in realtà di FTD (frontotemporal dementia), una malattia non ancora ben conosciuta, nota anche come morbo di Pick.

Ipotesi recenti suggeriscono che Maurice Ravel, il cui decesso è imputato ad una non ben identificata atrofia cerebrale o all’Alzheimer, soffrisse in realtà di FTD (frontotemporal dementia), una malattia non ancora ben conosciuta, nota anche come morbo di Pick.

Jacob Sudol è un giovane compositore americano. Giovane davvero, una volta tanto, essendo nato a Des Moines, Iowa, nel 1980.

Jacob Sudol è un giovane compositore americano. Giovane davvero, una volta tanto, essendo nato a Des Moines, Iowa, nel 1980. Wolfang Rihm è una figura abbastanza importante nella musica contemporanea tedesca. Nato nel 1952 a Karlsruhe, di formazione musicale tradizionale, pur avendo poi studiato con Stockhausen non aderì mai completamente allo sperimentalismo di Darmstadt e Donaueschingen.

Wolfang Rihm è una figura abbastanza importante nella musica contemporanea tedesca. Nato nel 1952 a Karlsruhe, di formazione musicale tradizionale, pur avendo poi studiato con Stockhausen non aderì mai completamente allo sperimentalismo di Darmstadt e Donaueschingen.

Sentite un po’ questo ragazzo finlandese. In effetti è un po’ più pop di quello che metto di solito, ma mi colpisce il modo in cui passa con assoluta tranquillità dalla tonalità, al rumorismo, alla new age, al delirio.

Sentite un po’ questo ragazzo finlandese. In effetti è un po’ più pop di quello che metto di solito, ma mi colpisce il modo in cui passa con assoluta tranquillità dalla tonalità, al rumorismo, alla new age, al delirio.

“Retorno a la nada”, album di debutto di David Velez (aka Lezrod) e della netlabel Zymogen, pieno di ritmi obliqui su cui si muovono drone, beep, click e disturbanti scricchiolii.

“Retorno a la nada”, album di debutto di David Velez (aka Lezrod) e della netlabel Zymogen, pieno di ritmi obliqui su cui si muovono drone, beep, click e disturbanti scricchiolii. Century of Aeroplanes, di cui

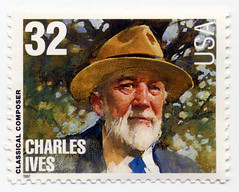

Century of Aeroplanes, di cui  Oltre a quello di Messiaen, c’è un secondo centenario quest’anno: quello della nascita del compositore americano

Oltre a quello di Messiaen, c’è un secondo centenario quest’anno: quello della nascita del compositore americano

Il 2008 è il centenario della nascita di

Il 2008 è il centenario della nascita di

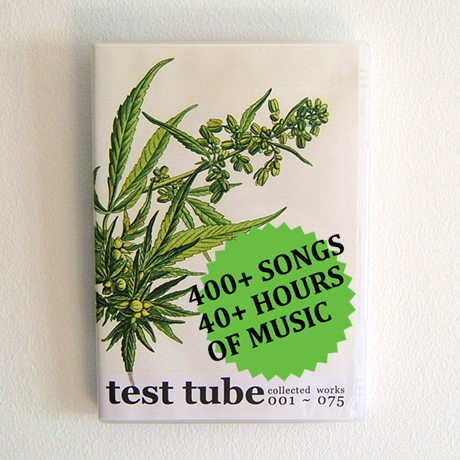

La netlabel portoghese

La netlabel portoghese  Jo Jena è un gruppo sperimentale di Francoforte dalla cui produzione ho pescato questo album del 2005 che alterna ritmi e ‘ronzii’ (è questo il significato acustico di ‘drone’) in modo eccellente.

Jo Jena è un gruppo sperimentale di Francoforte dalla cui produzione ho pescato questo album del 2005 che alterna ritmi e ‘ronzii’ (è questo il significato acustico di ‘drone’) in modo eccellente. Ho visitato

Ho visitato  Lezrod è il nick del colombiano David Velez.

Lezrod è il nick del colombiano David Velez.

È morto il compositore

È morto il compositore  Cosa ci fa Alfred Hitchcock sul

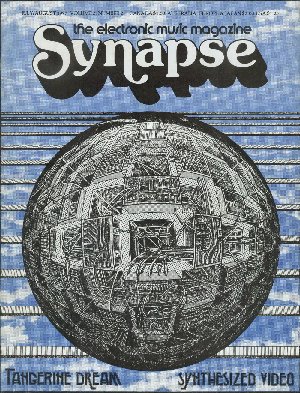

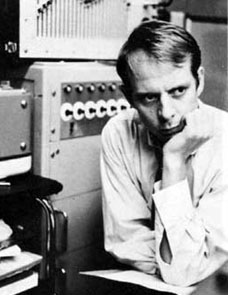

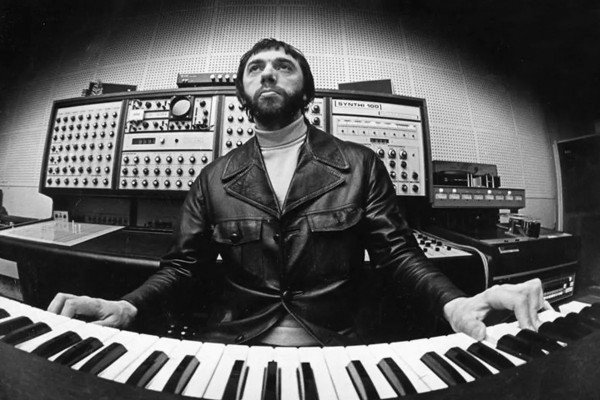

Cosa ci fa Alfred Hitchcock sul  Ecco come si faceva musica elettronica qualche anno fa. Visto che qualcuno di voi ci è nato nel 1982, magari così si fa un’idea.

Ecco come si faceva musica elettronica qualche anno fa. Visto che qualcuno di voi ci è nato nel 1982, magari così si fa un’idea. Post-conceptual digital artist and theoretician Joseph Nechvatal pushes his experimental investigations into the blending of computational virtual spaces and the corporeal world into the sonic register.

Post-conceptual digital artist and theoretician Joseph Nechvatal pushes his experimental investigations into the blending of computational virtual spaces and the corporeal world into the sonic register.

Dai

Dai  A differenza di OnClassical, Classica Viva vende principalmente tracce singole in formato MP3, quasi tutte a € 0.50 ciascuna (per tutte c’è un preview) indirizzandosi, così, verso un target un po’ diverso da quello dei già citati colleghi. È difficile, infatti, che un audiofilo si accontenti di un MP3, ma d’altra parte in questo modo è molto più facile raggiungere settori di pubblico più vasti.

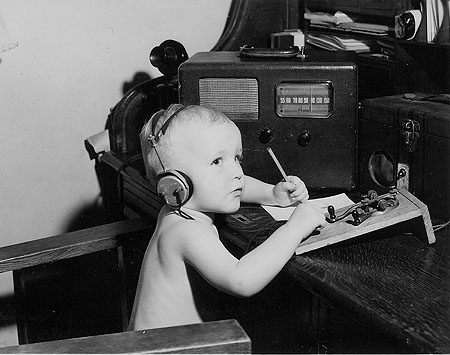

A differenza di OnClassical, Classica Viva vende principalmente tracce singole in formato MP3, quasi tutte a € 0.50 ciascuna (per tutte c’è un preview) indirizzandosi, così, verso un target un po’ diverso da quello dei già citati colleghi. È difficile, infatti, che un audiofilo si accontenti di un MP3, ma d’altra parte in questo modo è molto più facile raggiungere settori di pubblico più vasti. La prima volta che incontrai Barry Truax (nella foto a 2/3 anni), al CSC di Padova alla fine degli anni ’70, io ero uno studente e lui era già un guru della computer music che aveva al suo attivo il POD (un software per la composizione assistita da computer) e una convincente sistematizzazione compositiva della modulazione di frequenza e alcuni brani che la sfruttavano, come Sonic Landscape e Androginy.

La prima volta che incontrai Barry Truax (nella foto a 2/3 anni), al CSC di Padova alla fine degli anni ’70, io ero uno studente e lui era già un guru della computer music che aveva al suo attivo il POD (un software per la composizione assistita da computer) e una convincente sistematizzazione compositiva della modulazione di frequenza e alcuni brani che la sfruttavano, come Sonic Landscape e Androginy.

Un buon lavoro questo

Un buon lavoro questo

La netlabel bulgara Mahorka pubblica ben tre volumi di musica per ascensori.

La netlabel bulgara Mahorka pubblica ben tre volumi di musica per ascensori.

Maybe someone remember this 1973 vinyl (now out of print) called Tibetan Bells by Henry Wolff and Nancy Hennings.

Maybe someone remember this 1973 vinyl (now out of print) called Tibetan Bells by Henry Wolff and Nancy Hennings.

Difficile scrivere poche righe su

Difficile scrivere poche righe su

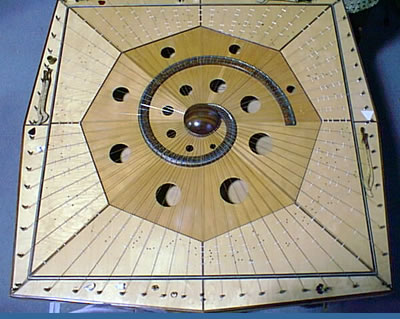

The Danses sacree et profane were composed by Claude Debussy (1862–1918) at the request of the firm of Pleyel, manufacturers of musical instruments. In 1894 Gustave Lyon had invented a new mechanism for the harp, which provided the full chromatic scale by the use of twelve strings to the octave, crossing each other at an angle so that the diatonic and chromatic notes were clearly distinguished, yet both accessible to the player’s hands. A rough analogy is the arrangement in which a piano has the black keys raised above the white. The previous design of the harp had had only seven strings to the octave, with a series of pedals supplied to provide chromatic notes.

The Danses sacree et profane were composed by Claude Debussy (1862–1918) at the request of the firm of Pleyel, manufacturers of musical instruments. In 1894 Gustave Lyon had invented a new mechanism for the harp, which provided the full chromatic scale by the use of twelve strings to the octave, crossing each other at an angle so that the diatonic and chromatic notes were clearly distinguished, yet both accessible to the player’s hands. A rough analogy is the arrangement in which a piano has the black keys raised above the white. The previous design of the harp had had only seven strings to the octave, with a series of pedals supplied to provide chromatic notes.

“C’è un quadro di Klee che si chiama Angelus Novus. Vi è rappresentato un angelo che sembra in procinto di allontanarsi da qualcosa su cui ha fisso lo sguardo. I suoi occhi sono spalancati, la bocca è aperta, e le ali sono dispiegate. L’angelo della storia deve avere questo aspetto. Ha il viso rivolto al passato. Là dove davanti a noi appare una catena di avvenimenti, egli vede un’unica catastrofe, che ammassa incessantemente macerie su macerie e le scaraventa ai suoi piedi. Egli vorrebbe ben trattenersi, destare i morti e riconnettere i frantumi. Ma dal paradiso soffia una bufera, che si è impigliata nelle sue ali, ed è così forte che l’angelo non può più chiuderle. Questa bufera lo spinge inarrestabilmente nel futuro, a cui egli volge le spalle, mentre cresce verso il cielo il cumulo delle macerie davanti a lui. Ciò che noi chiamiamo il progresso, è questa bufera”

“C’è un quadro di Klee che si chiama Angelus Novus. Vi è rappresentato un angelo che sembra in procinto di allontanarsi da qualcosa su cui ha fisso lo sguardo. I suoi occhi sono spalancati, la bocca è aperta, e le ali sono dispiegate. L’angelo della storia deve avere questo aspetto. Ha il viso rivolto al passato. Là dove davanti a noi appare una catena di avvenimenti, egli vede un’unica catastrofe, che ammassa incessantemente macerie su macerie e le scaraventa ai suoi piedi. Egli vorrebbe ben trattenersi, destare i morti e riconnettere i frantumi. Ma dal paradiso soffia una bufera, che si è impigliata nelle sue ali, ed è così forte che l’angelo non può più chiuderle. Questa bufera lo spinge inarrestabilmente nel futuro, a cui egli volge le spalle, mentre cresce verso il cielo il cumulo delle macerie davanti a lui. Ciò che noi chiamiamo il progresso, è questa bufera”

A good way to celebrate Christmas.

A good way to celebrate Christmas. Il 24 Dicembre 1935, dopo aver completato il concerto per violino e orchestra, moriva Alban Berg (1885-1935), grande sostenitore e scardinatore della dodecafonia.

Il 24 Dicembre 1935, dopo aver completato il concerto per violino e orchestra, moriva Alban Berg (1885-1935), grande sostenitore e scardinatore della dodecafonia.

Per gli amanti della musica antica, ecco un buon modo per risolvere il problema dell’elevato costo degli strumenti:

Per gli amanti della musica antica, ecco un buon modo per risolvere il problema dell’elevato costo degli strumenti:

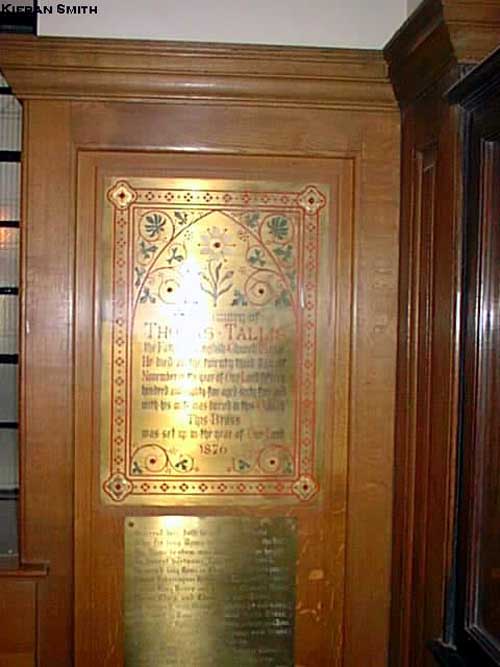

Questo è quel poco che sappiamo della storia di Spem in Alium, il mottetto in 40 parti, scritto da Thomas Tallis verso il 1570 per 8 gruppi di 5 voci ciascuno.

Questo è quel poco che sappiamo della storia di Spem in Alium, il mottetto in 40 parti, scritto da Thomas Tallis verso il 1570 per 8 gruppi di 5 voci ciascuno.

Maderna (nella foto, con Berio) è morto il 13 Novembre 1973 a soli 53 anni.

Maderna (nella foto, con Berio) è morto il 13 Novembre 1973 a soli 53 anni.

Ogni tanto qualcuno mi domanda se ci sia qualche gruppo pop che mi piace.

Ogni tanto qualcuno mi domanda se ci sia qualche gruppo pop che mi piace.

Il rivolgersi a oriente tipico della seconda metà degli anni ’60 coinvolge anche Stockhausen che, nel fatidico 1968, abbraccia con decisione le filosofie orientali. Passando attraverso Stimmung, giungerà gradualmente alla definizione di una musica intuitiva, praticamente priva di partitura

Il rivolgersi a oriente tipico della seconda metà degli anni ’60 coinvolge anche Stockhausen che, nel fatidico 1968, abbraccia con decisione le filosofie orientali. Passando attraverso Stimmung, giungerà gradualmente alla definizione di una musica intuitiva, praticamente priva di partitura Questo non significa che tutta l’opera, che dura ben 70 minuti, sia costituita da un unico accordo, ma quasi. Un accordo di 6 note implica una gamma di possibilità che va dalle singole note fino ad accordi composti di 2, 3, 4, 5 e finalmente 6 note. Inoltre, ogni nota può essere potenzialmente eseguita da più di un cantante (tutti dovrebbero poter cantare il RE).

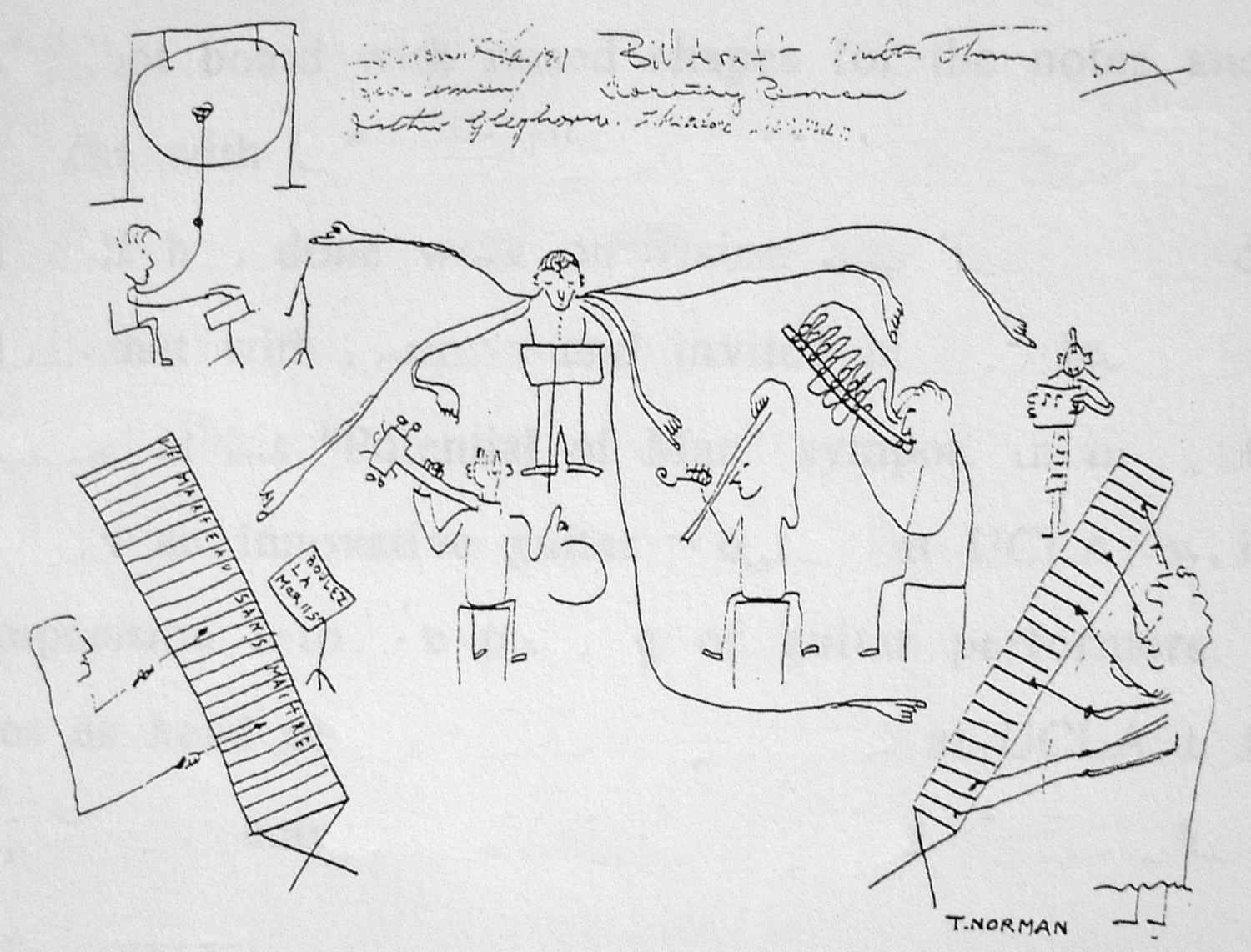

Questo non significa che tutta l’opera, che dura ben 70 minuti, sia costituita da un unico accordo, ma quasi. Un accordo di 6 note implica una gamma di possibilità che va dalle singole note fino ad accordi composti di 2, 3, 4, 5 e finalmente 6 note. Inoltre, ogni nota può essere potenzialmente eseguita da più di un cantante (tutti dovrebbero poter cantare il RE). Questo ironico schizzo per un busto di Satie, firmato da lui stesso, reca la scritta “Sono venuto al mondo molto giovane in un tempo molto vecchio”.

Questo ironico schizzo per un busto di Satie, firmato da lui stesso, reca la scritta “Sono venuto al mondo molto giovane in un tempo molto vecchio”. Nato in Ucraina (allora Russia) nel 1893 e morto negli USA nel 2002, alla rispettabile età di 108 anni, Leo Ornstein può essere considerato uno dei principali compositori sperimentali del primo ‘900.

Nato in Ucraina (allora Russia) nel 1893 e morto negli USA nel 2002, alla rispettabile età di 108 anni, Leo Ornstein può essere considerato uno dei principali compositori sperimentali del primo ‘900.

Spero che qualcuno si ricordi che il 2006, oltre all’ennesimo anno mozartiano, è anche il centenario della nascita di Dmitrij Šostakovič (anche noto come Shostakovich o Schostakowitsch, in cirillico Дмитрий Дмитриевич Шостакович, San Pietroburgo, 25 settembre 1906 – Mosca, 1975).

Spero che qualcuno si ricordi che il 2006, oltre all’ennesimo anno mozartiano, è anche il centenario della nascita di Dmitrij Šostakovič (anche noto come Shostakovich o Schostakowitsch, in cirillico Дмитрий Дмитриевич Шостакович, San Pietroburgo, 25 settembre 1906 – Mosca, 1975).