Anni fa, Tom Waits, che notoriamente non è mai accomodante verso le corporation, ha scritto una bella lettera polemizzando con i musicisti che permettono che le loro canzoni vengano inserite negli spot commerciali in cambio di una manciata di soldi.

Anni fa, Tom Waits, che notoriamente non è mai accomodante verso le corporation, ha scritto una bella lettera polemizzando con i musicisti che permettono che le loro canzoni vengano inserite negli spot commerciali in cambio di una manciata di soldi.

La lettera, pubblicata, fra gli altri da Dangerous Visions, Letters of Note e The Nation, contiene alcuni concetti non banali, che a una prima lettura del fenomeno possono sfuggire. Per esempio:

- quando vendete alle aziende la vostra musica, vendete anche il vostro pubblico perché loro la useranno per convincere la gente ad acquistare automobili, drink e biancheria;

- le corporation sperano di dirottare i ricordi di una cultura verso i loro prodotti (che invece non ne sono per nulla collegati);

- loro vogliono il pubblico di un artista, la sua credibilità, la sua reputazione e tutta l’energia che le sue canzoni hanno concentrato con il passare degli anni.

Mi rendo conto che parlare di etica nel 2014 può sembrare perfino da bacchettoni, ma la realtà è che un musicista che raggiunge la notorietà è portatore di un certo grado di potere sulla gente e non deve permettere che venga utilizzato per qualsiasi cosa in cambio di denaro. È il lato bello del copyright: la possibilità che il compositore ha di vietare che la propria musica venga utilizzata in determinati contesti. E non è detto che ci si perda, come Ligeti e lo stesso Tom Waits insegnano: a volte le corporation sono così sfacciate che, chiamandole in causa, si vince (Ligeti ha vinto contro i produttori do 2001 Odissea dello Spazio che avevano smontato e usato il suo brano Atmosphères, mentre Tom Waits ha ottenuto 2.6 milioni di $ da Frito-Lay che aveva rifatto una sua canzone).

Ecco la lettera originale, già ripubblicata qui

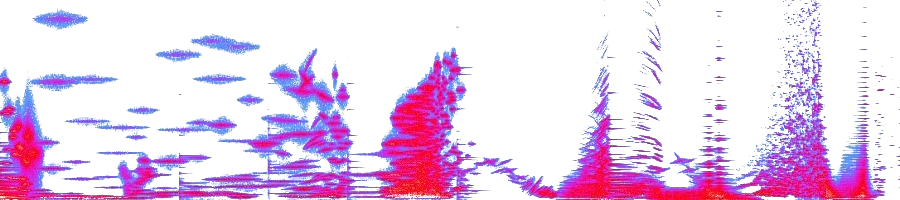

Thank you for your eloquent “rant” by John Densmore of The Doors on the subject of artists allowing their songs to be used in commercials [“Riders on the Storm,” July 8]. I spoke out whenever possible on the topic even before the Frito Lay case (Waits v. Frito Lay), where they used a sound-alike version of my song “Step Right Up” so convincingly that I thought it was me. Ultimately, after much trial and tribulation, we prevailed and the court determined that my voice is my property.

Songs carry emotional information and some transport us back to a poignant time, place or event in our lives. It’s no wonder a corporation would want to hitch a ride on the spell these songs cast and encourage you to buy soft drinks, underwear or automobiles while you’re in the trance. Artists who take money for ads poison and pervert their songs. It reduces them to the level of a jingle, a word that describes the sound of change in your pocket, which is what your songs become. Remember, when you sell your songs for commercials, you are selling your audience as well.

When I was a kid, if I saw an artist I admired doing a commercial, I’d think, “Too bad, he must really need the money.” But now it’s so pervasive. It’s a virus. Artists are lining up to do ads. The money and exposure are too tantalizing for most artists to decline. Corporations are hoping to hijack a culture’s memories for their product. They want an artist’s audience, credibility, good will and all the energy the songs have gathered as well as given over the years. They suck the life and meaning from the songs and impregnate them with promises of a better life with their product.

Eventually, artists will be going onstage like race-car drivers covered in hundreds of logos. John, stay pure. Your credibility, your integrity and your honor are things no company should be able to buy.

TOM WAITS