Continuiamo con Scelsi perché è un compositore relativamente poco conosciuto in Italia, ma osannato all’estero, soprattutto in Francia, dove è considerato l’antesignano della musica spettrale. In realtà Giacinto Scelsi è un grande compositore, come tutti con alti e bassi, ma ha contribuito a creare alcuni degli stilemi che hanno permeato tutta la musica degli anni ’60 e ’70, prima fra tutte l’idea del suono che si sviluppa a partire da una singola nota.

Qui abbiamo Uaxuctum del 1966, un brano molto drammatico, come testimonia il sottotitolo “la leggenda della città maya che si autodistrusse per motivi religiosi“. Il brano è idealmente diviso in cinque movimenti che corrispondono ad altrettanti video in You Tube. Come al solito metto la prima e i link alle altre parti,

Questo il commento di Todd McComb su classical.net

This extraordinary piece is in five movements, totaling approximately twenty minutes. In addition to the large chorus, written at an astonishingly difficult technical level, the work is scored for: four vocal soloists (two sopranos, two tenors, electronically amplified), ondes Martenot solo, vibraphone, sistrum, Eb clarinet, Bb clarinet, bass clarinet, four horns, two trumpets, three trombones, bass tuba, double bass tuba, six double basses, timpani and seven other percussionists (playing on such instruments as the rubbed two-hundred liter can, a large aluminum hemisphere, and a two-meter high sheet of metal). The chorus is written in ten and twelve parts, incorporating all variety of microtonal manipulations, as well as breathing and other guttural and nasal sounds. This piece is certainly Scelsi’s most difficult to perform, and was not premiered until October 12th, 1987 by the Cologne Radio Chorus and Symphony Orchestra. Uaxuctum is subtitled: “The legend of the Maya city, destroyed by themselves for religious reasons” and corresponds to an actual Maya city in Peten, Guatemala which flourished during the first millennium AD; in addition, the Mexican state of Oaxaca comes from the same ancient meso-American root.

This is an intensely dramatic work, and the most bizarre in Scelsi’s output. It depicts the end of an ancient civilization – residing in Central America, but with mythical roots extending back to Egypt and beyond – it is the last flowering of a mystical and mythological culture which was slowly destroyed by our modern world. In this case, Scelsi says, the Mayans made a conscious decision to end the city themselves. Uaxuctum incorporates harmonic elements throughout, and is extremely difficult to come to terms with.

The first movement, the longest of the five, is a grand overture; it begins in quiet contemplation, only to be interrupted by the violent mystical revelation of the chorus propelling this story into the present from the distant past, and then sinking back into meditative tones with a presentiment of the upcoming adventure. In the wild and dramatic second movement, we enter the world of the Mayans, complete with mysticism in all aspects of life; it is an incredible and violent tour-de-force of orchestral writing. The short third movement opens with an atmosphere of foreboding, building into a realization of things to come, and reaching a decision. After a few seconds of silence, the city of Uaxuctum is quickly destroyed and abandoned. The fourth movement is dominated by the chorus throughout, and presents the wisdom gained by the Mayans as they gradually fade into oblivion. The fifth movement returns to the opening mood, and gives a dim recollection of the preceding events which have now been told, in abstract form, to our time and civilization.

There really are no proper words to describe this amazing piece, which presents Scelsi at his most daring and innovative. It is a world all to itself, and a warning.

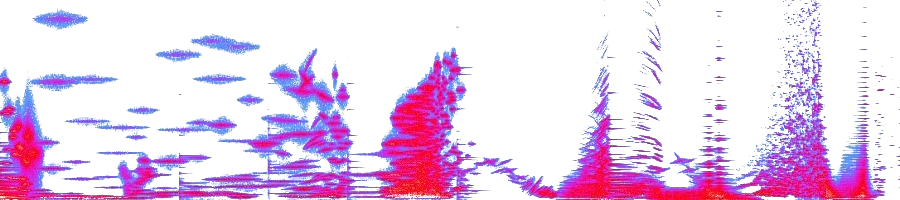

Here in binaural recording. Headphones are mandatory to hear the binaural effect.

Orchestre philharmonique et Choeur de Radio France – Aldo Brizzi