Ecco un brano di Helmut Lachenmann, Guero, del 1970, definito dall’autore come uno studio per piano.

I suoni che sentirete, però, non hanno niente a che fare con il pianoforte a cui siete abituati (raramente si sente una nota), ma assomigliano piuttosto a quelli dell’omonimo strumento a percussione, il guiro (nella dizione originale).

Non solo, ma Lachenmann non utilizza nemmeno tutta quella serie di sonorità pianistiche che fanno parte dei “rumori pedalizzati” basata su pizzicati o percussioni che creano risonanze sostenute dal pedale, già utilizzata nella letteratura pianistica contemporanea.

In effetti la musica di Lachenmann è definita come musica concreta strumentale, a significare che il suo linguaggio strumentale abbraccia l’intero mondo sonoro ottenibile dallo strumento, anche ricorrendo a tecniche decisamente non convenzionali.

Grazie a questo video, è possibile vedere come vengono ottenute le sorprendenti sonorità di questo “studio” per piano. L’esecutore è lo stesso Lachenmann.

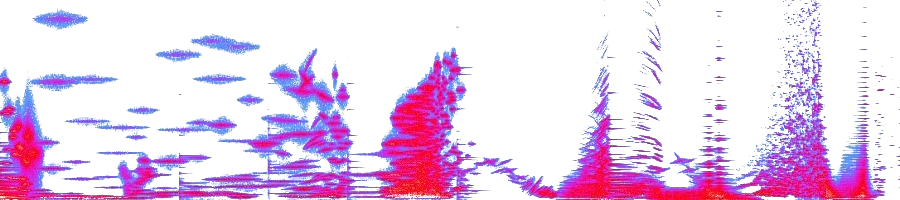

qui con la partitura