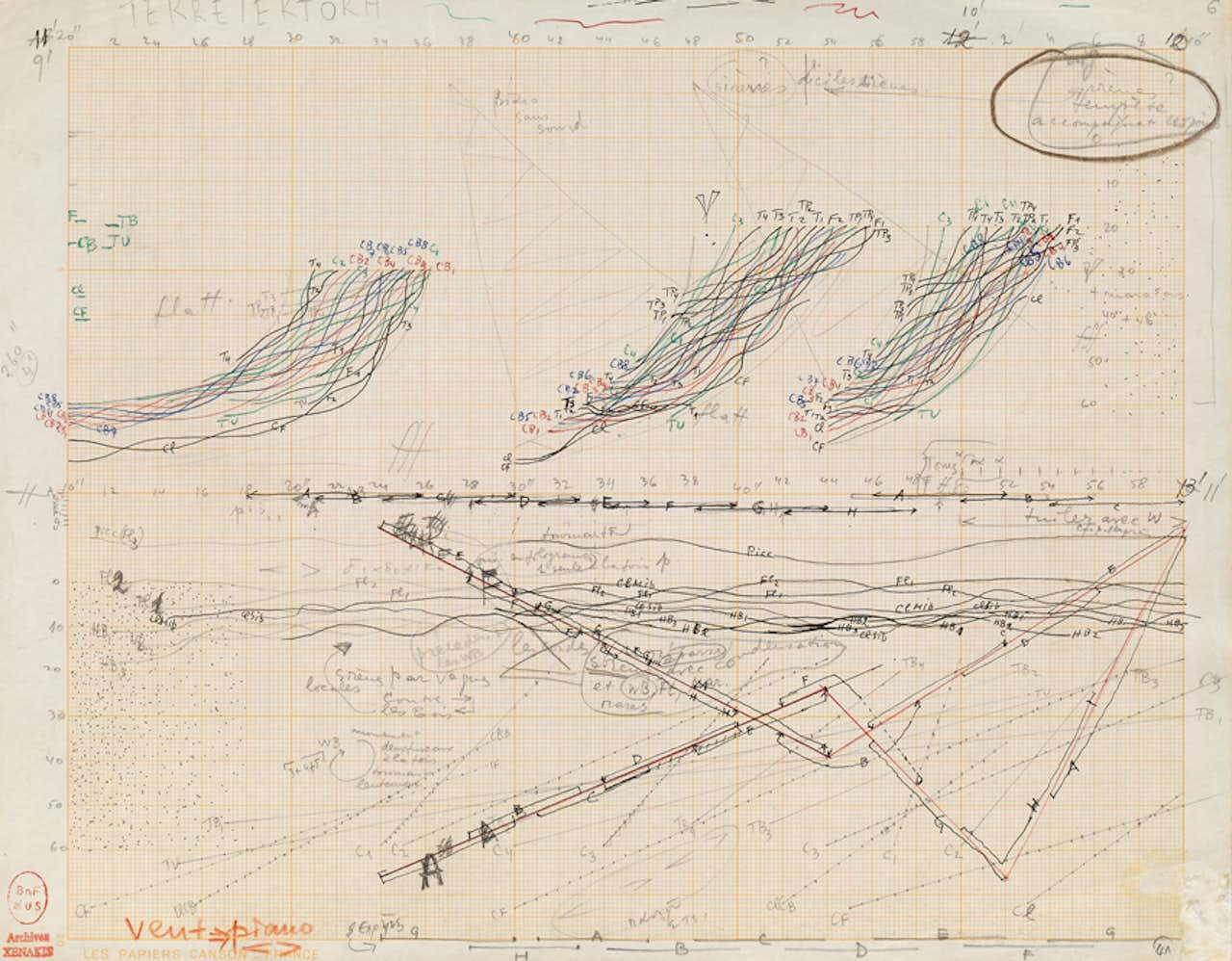

Morton Feldman: De Kooning (1963)

Morton Feldman’s elegant chamber work dedicated to the painter “De Kooning” and scored for horn, percussion, piano, violin, and cello was composed in 1963.

After composing works in the early 1950’s that were in graphic notation and left most of the musical parameters (pitch, duration, timbre, event occurence) to the discretion of the performers, Feldman became dissatisfied with the result because although this manner of composing freed the sounds it also freed the kind of subjective expression of the performers that could not create the kind of pure sound-making that Feldman envisioned.

He briefly returned to strictly notated works, found these too confining, and then created works in which most of the parameters were given except for duration and, consequently, coordination among the parts (“The O’Hara Songs” [1962], “For Franz Kline” [1962]). Following this, Feldman began to create works, like “De Kooning”, “False Relationships and the Extended Ending” (1968) and others, which alternate fully determined and indeterminate sections within the same work.

In “De Kooning”, there are coordinated chords (verticalities) and isolated events (single tones and intervals … verticalities stretched out horizontally or melodically) of a duration determined by the performers. The sequence of these single events is given however and players must enter before the last event has died out. These open sequences alternate with traditionally notated measures of rest with exact metronome markings, treating sound and silence in equivalent importance.

The total duration of “De Kooning” is open but tends to be between 14 and 1/2 minutes and 16 minutes. Tiny bells, tubular bells, and vibraphone are mixed with high piano tones and icy string harmonics creating a crystalline texture, that contrasts with a more muted texture of low tympani and bass and tenor drum rolls, pizzicati, low cello tones, low vibraphone notes, lower piano aggregates and sustained horn pitches. The materials are limited to a few gestures on each instrument and create “identities” of a sort (for example, the repeated “foghorn”-like horn notes, the percussion rolls, and so on) that can easily be followed by the ear. The variety of timbre combinations is astonishing and the tempo of their unfolding gives the listeners plenty of time to appreciate their quality. No particular programme is intended, but the changing timbres may spontaneous stimulate imagery for the listener. Or, for another listener, the joy may simply be in sheer richness of the sonic experience, for the sounds themselves.

[“Blue” Gene Tyranny, All Music Guide]

The Drawing Center

The Drawing Center Paul Morley recently spoke to Brian Eno for a BBC arena documentary in which Eno proved that he is always good for a controversial and catchy phrase about the music industry:

Paul Morley recently spoke to Brian Eno for a BBC arena documentary in which Eno proved that he is always good for a controversial and catchy phrase about the music industry:

A Million Billion is Ryan Smith based out of Queens, NYC. ‘Cavity Care’ is a collection of compositions that Ryan wrote in collaboration with several choreographers over the last 6 years.

A Million Billion is Ryan Smith based out of Queens, NYC. ‘Cavity Care’ is a collection of compositions that Ryan wrote in collaboration with several choreographers over the last 6 years. I like the rhythmic feeling of this work. Rhythm is the main stream around which all the sound moves. Rich rhythmic patterns that derivate from dub, hip hop, techno and other urban languages, but instead of driving us straight to the physical emotion center, they drive us to the ‘braindance’ center.

I like the rhythmic feeling of this work. Rhythm is the main stream around which all the sound moves. Rich rhythmic patterns that derivate from dub, hip hop, techno and other urban languages, but instead of driving us straight to the physical emotion center, they drive us to the ‘braindance’ center. Umbrellas in the Rain is the alias of an austrian musician from Vienna, and ‘Wieder Daheim’ – german for ‘Home Again’ – his first effort at creating something mature enough worth listening to (and worth releasing, for that matter…). Well, he did it, and with flying colours. ‘Wieder Daheim’ is a delicate collection of abstract songs that really grab one’s heart. They are experimental enough to wander in, but also emotional enough – to the point of being nostalgic – to keep us down to earth.

Umbrellas in the Rain is the alias of an austrian musician from Vienna, and ‘Wieder Daheim’ – german for ‘Home Again’ – his first effort at creating something mature enough worth listening to (and worth releasing, for that matter…). Well, he did it, and with flying colours. ‘Wieder Daheim’ is a delicate collection of abstract songs that really grab one’s heart. They are experimental enough to wander in, but also emotional enough – to the point of being nostalgic – to keep us down to earth.