Mauricio Kagel – Fürst Igor, Strawinsky (1982)

for bass voice, English horn, French horn, tuba, viola and two percussionists

“Fürst Igor, Strawinsky” was commissioned for the Biennale in Venice on the occasion of the centenary of Stravinsky’s birth. It received its premiere performance in the church on the cemetery-island San Michele, where Stravinsky is buried. As hinted in Kagel’s note for the Biennale programme, the sacred, theatrical ambience of this location was a lasting source of inspiration to the composer, who is especially susceptible to spectular sites. However, it proved impossible to carry out Kagel’s original vision of a funeral procession of gondolas transporting the audience to the performance: a thunderstorm erupted at precisely the wrong moment, bringing this cortege to nought. All that remained was the concert in the cemetery chapel.

The piece is scored for a chamber ensemble of bass voice, English horn, French horn, tuba, viola and two percussionists. The instruments lie in the middle and low registers, creating a plush, darkening sound. Besides the conventional percussion instruments, there is also a series of unusual sound-producing devices of indefinite pitch such as iron chains, cocoanut shells, the roaring of lions, wooden planks, an anvil, ratchets and metal tubs. These too have largely a muffled timbre. Kagel – who once referred to timbre as the “paramount material” of a work – here proceeds from a precisely conceived sound-image with associations related to the meaning of the composition. This sound-image is expressed not only in the choice of instruments, but also in the numerous performance instructions included in the score with the aim of making the composer’s intentions as unambiguous as possible.

The text derives from Borodin’s opera “Prince Igor”. Apart from a few repetitions to heighten the expression and a cut required for the sake of compression, the composer retains the whole of the text to Igor’s aria in Act 2, in which the captive Prince sings of his despair at his own fate and that of prostrate Russia. A comparison of Kagel’s setting and Borodin’s original, however revealing of Kagel’s methods, cannot be undertaken here. However, we can at least give a rough sketch of the way in which the picture of Igor changes in this re-composition. In Borodin’s work the Prince, though imprisoned, is still in possession of his traits as a ruler, while Kagel’s work reduces him to a complainer who has sacrificed, if not his dignity, at least any sense of his station. He gives free rein to his feelings in a Lamento with pronounced elements of self-castigation; ultimately, his deep despair borders on insanity. This is apparent, for example, in a key passage beginning with the words “geschändet ist mein Ruhm” (my fame has been desecrated), to which Kagel devotes three times as much time as Borodin, and also in the dynamic and expressive climax of the work, just after the half-way point, where the soloist, at the words “und dafür gibt man mir die Schuld” (and I am held guilty of this), is told to break out into “desperate, distorted laughter”. In the long crescendo which precedes this climax the voice part, which had previously been notated precisely, is rendered only in approximate pitch-curves – the inner turmoil bursts the form.

Although this piece is unusually expressive by Kagel’s standards, it cannot simply be pigeon-holed as an “expressive composition”. Kagel’s espressivo capsizes into the grotesque. One sign of this is the nagging, crazed, laughing sounds required of the instruments; another is the direction to the soloist during the preceding crescendo to be “excessively dramatic”, and Kagel’s helpful suggestion that he try to caricature classical Japanese theatre. Seriousness and irony, tragedy and ridiculousness merge in this paradoxical piece, and Kagel makes use of the shifting expression like a mask behind which lie his feelings, now hidden, now exposed. It is not only in the pun of the title, in the neo-classical figures such as scalar passages and parallel 7th chords, but also in this masquerade that Kagel reveals his spiritual affinity with the secretive dedicatee of his piece.

Max Nyffeler (Translation: J. Bradford Robinson)

Mauricio Kagel: Speech delivered on 5 October 1982 in the Chiesa di San Michele in Isola, located in San Michele Cemetery, Venice, on the occasion of the world premiere of “Fürst Igor, Strawinsky”.

Dear Friends and Strangers,

The news of Stravinsky’s burial in Venice gave me pause at the time to consider whether a touch of the master’s irony might also be buried in this wish of his. He was so fond of the damp – especially of that kind which is surrounded by glass – that it must have given him untold pleasure to have found his final resting place in this unique city where dampness is ever-present. We, too, who honour his memory today in our jovial manner, should take satisfaction in his decision: Stravinsky is ideally preserved in Venice, and forever within easy reach of one of the most crucial necessities of his former daily existence.

And yet – what ambiguity!

For it was precisely in the dryness, the objectivity of his music that Stravinsky – that grandseigneur of the mind and body, never content unless food and service were of the highest calibre – discovered that dimension which enabled him to turn his eye inward with such infinite profundity. His works are living documents of an apparent dichotomy. Passion and computation, unfettered inspiration and rational ingenuity, the sacred and the heathen – all mutually fertilize each other to produce an oeuvre which is well described by several expressions from the musicians’ lingua franca :sempre con passione ma senza rubato; con molta tenerezza ma non piangendo; con piacere, mai a piacere; musica pratica ma non tanto, musica poetica al piu possibile, musica viva da capo al fine.

For me, it is of course a great distinction to honour Stravinsky on this occasion and in this public forum. I belong to a generation of composers who were left with the unpleasant legacy of a family feud to which, pro or contra, we had in fact nothing new to contribute. The choice posited in Schoenberg’s canon “Tonal oder Atonal” has long, indeed has always been a question of sensibility and intelligent application rather than a hard and fast principle. Today, we no longer bother our heads by confusing a method of composition with the aesthetic of craftsmanship. I hope this will remain so in music history for a long time to come.

Stravinsky had much to offer all of us who practice music as a mental discipline. For this reason, we composers – who view the possibility of musical expression as a confirmation for many things that make our lives worth living – are very much in his debt. The very existence of a classical composer – particularly (sarcasm notwithstanding) a “classical modern” composer – is a clear challenge to anyone dedicated to the discovery of new, present worlds of music. It is my firm hope that my “Fürst Igor, Strawinsky” will prove to our honoured forebear that a goodly portion of his ‘attitude and doctrine consisted nor merely of contradictions and opposites, but also of a high-minded twinkling of the eye. In this sense my work is intended as an homage, without ambiguity: senza doppio (colpo) di lingua.

[text from ANABlog]

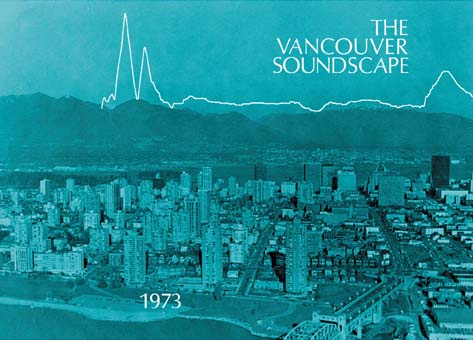

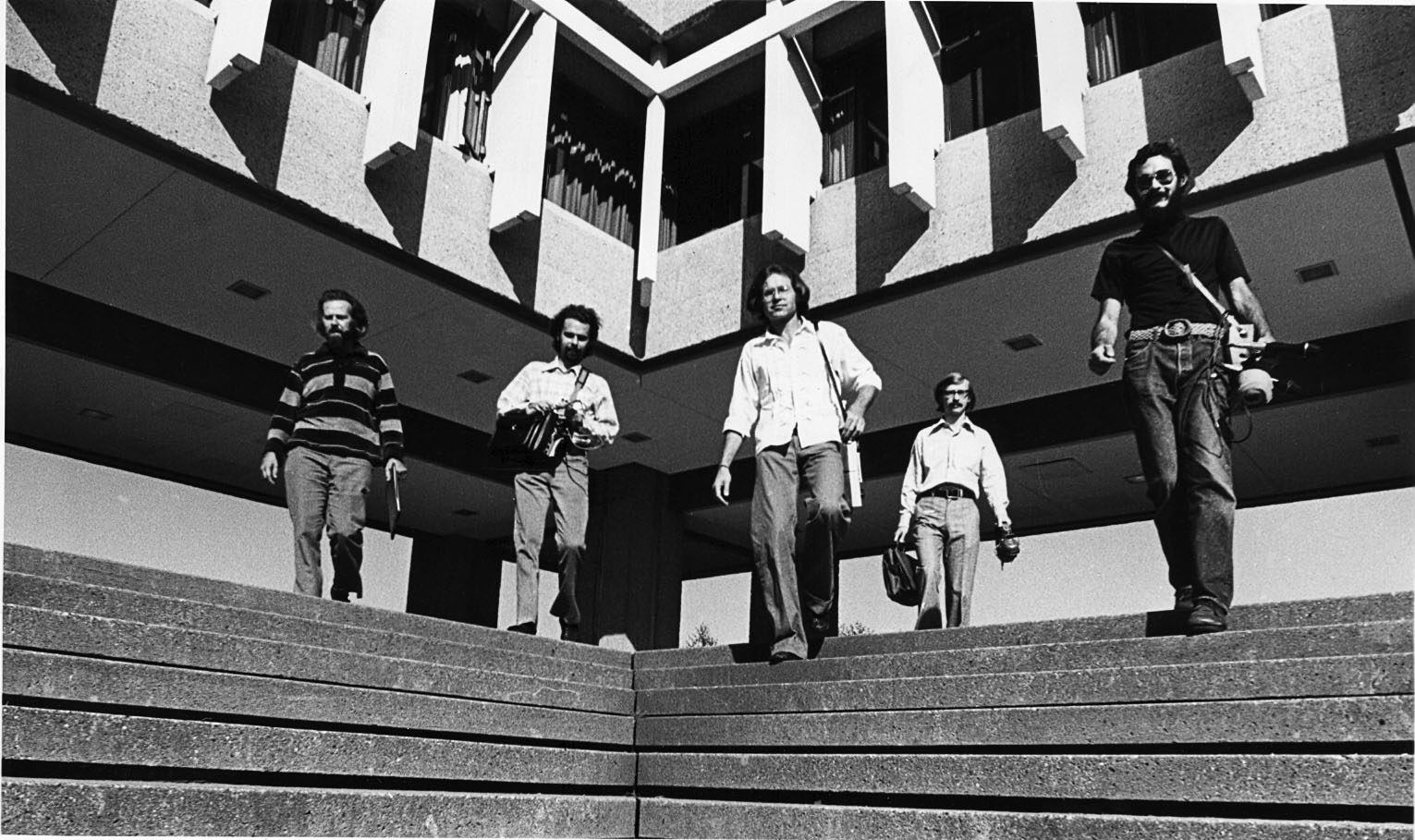

The World Soundscape Project (WSP) was established as an educational and research group by R. Murray Schafer at Simon Fraser University during the late 1960s and early 1970s. It grew out of Schafer’s initial attempt to draw attention to the sonic environment through a course in noise pollution, as well as from his personal distaste for the more raucous aspects of Vancouver’s rapidly changing soundscape. This work resulted in two small educational booklets, The New Soundscape and The Book of Noise, plus a compendium of Canadian noise bylaws. However, the negative approach that noise pollution inevitably fosters suggested that a more positive approach had to be found, the first attempt being an extended essay by Schafer (in 1973) called ‘The Music of the Environment’, in which he describes examples of acoustic design, good and bad, drawing largely on examples from literature.

The World Soundscape Project (WSP) was established as an educational and research group by R. Murray Schafer at Simon Fraser University during the late 1960s and early 1970s. It grew out of Schafer’s initial attempt to draw attention to the sonic environment through a course in noise pollution, as well as from his personal distaste for the more raucous aspects of Vancouver’s rapidly changing soundscape. This work resulted in two small educational booklets, The New Soundscape and The Book of Noise, plus a compendium of Canadian noise bylaws. However, the negative approach that noise pollution inevitably fosters suggested that a more positive approach had to be found, the first attempt being an extended essay by Schafer (in 1973) called ‘The Music of the Environment’, in which he describes examples of acoustic design, good and bad, drawing largely on examples from literature.

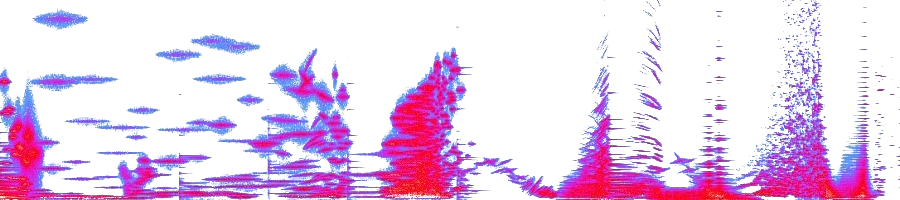

Nanimo nai wakusei means “empty planets” in Japanese and is an apt description for key elements of Tim Salden’s music as Osoroshisa. It reflects the width of uninhabited and lonesome worlds and how time becomes a secondary factor on an empty planet that lacks any point of reference for perceiving its continuous passage. In the broader sense, it may also refer to isolated persons living in a solar system of their own, without a way of taking notice of other worlds apart from theirs and where chains of events have gradually been replaced by a constant train of thoughts. Accordingly, the music is located between drone and dark ambient without being particularly representative of either genre and evolves slowly, with recurrent figures weaved into persistent drones and subtle changes in modulation rather than thematic variation and progression.

Nanimo nai wakusei means “empty planets” in Japanese and is an apt description for key elements of Tim Salden’s music as Osoroshisa. It reflects the width of uninhabited and lonesome worlds and how time becomes a secondary factor on an empty planet that lacks any point of reference for perceiving its continuous passage. In the broader sense, it may also refer to isolated persons living in a solar system of their own, without a way of taking notice of other worlds apart from theirs and where chains of events have gradually been replaced by a constant train of thoughts. Accordingly, the music is located between drone and dark ambient without being particularly representative of either genre and evolves slowly, with recurrent figures weaved into persistent drones and subtle changes in modulation rather than thematic variation and progression.