Tripla maledizione, scrivere necrologi è deprimente.

Tripla maledizione, scrivere necrologi è deprimente.

Due giorni fa è scomparso Mauricio Kagel. Argentino, trasferito in Germania fin dal 1957, Kagel è stato sempre una figura provocatoria e diversa nel panorama della musica europea.

Interessato al teatro musicale, alla parte “scenica” della musica non meno che alla musica stessa, ha saputo creare opere che vanno oltre entrambi questi aspetti, fino a qualificarsi come lavori metamusicali. Da Exotica (1971-72) e Der Schall (1968), in cui gli esecutori, che di solito sono degli esperti dello strumento, sono costretti a confrontarsi con strumenti che non sanno suonare a Musik fur Renaissance Instrumente (1965/66) dove gli strumenti antichi vengono utilizzati per creare sonorità del tutto nuove, fino ad opere lucidamente provocatorie come Con voce (1972), dove tre attori muti si presentano sulla scena e, dopo un lungo imperterrito silenzio, mimano brevi frammenti di concerto, in atteggiamenti ridicoli e dissacranti o Recitativarie (1971-72), dove una clavicembalista-cantante inscena una delirante lettura musicale o ancora Match (1964) per due violoncelli e percussioni che è la trascrizione musicale di un incontro di pugilato.

Mi preme citare anche Hétérophonie (1961), un brano per orchestra interamente formato da materiale altrui, desunto da opere di autori del ‘900 come Debussy, Schoenberg, Stravinskij, Ravel, Varèse, Boulez, Stockhausen. La citazione portata all’eccesso e fatta arte.

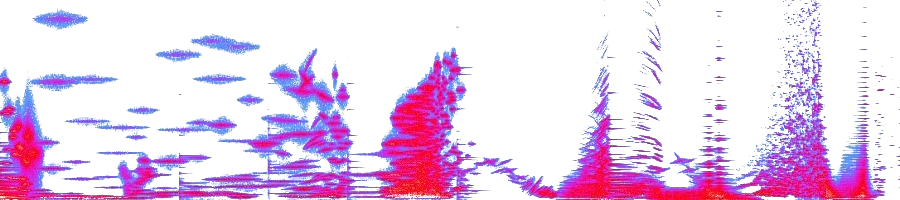

È giusto dire che, in Kagel, la musica si faceva teatro e a volte anche film come per Ludwig van (1970) uno dei suoi lavori più noti. Si tratta di una riproduzione di una visita fittizia allo studio di Beethoven nella sua casa di Bonn. Molte scene sono tappezzate dagli spartiti della musica di Beethoven e la colonna sonora è costituita dai brani musicali che appaiono negli spartiti inseriti nelle inquadrature. La musica è come deformata timbricamente ed ha un suono distorto che lascia comunque riconoscere le autentiche melodie beethoveniane. In altre scene il film mostra delle parodie di trasmissioni radio televisive connesse alla commemorazione del “Beethoven Year 1770”.

La sua produzione, in vari campi, è molto vasta ed è impossibile darle qui lo spazio che merita, ma ne riparleremo.

Potete trovate altra musica/film di Kagel in AGP (num. 2, 40, 41, 104), su UBUWeb e qui in MGBlog.

Su wikipedia in spagnolo trovate anche il catalogo delle opere.

Tripla maledizione, scrivere necrologi è deprimente.

Tripla maledizione, scrivere necrologi è deprimente.

Uno dei desideri di

Uno dei desideri di