Negli anni ’60, Stockhausen raccolse intorno a sè un piccolo gruppi di esecutori e tecnici con i quali lavorare e sperimentare. Con questo gruppo, che è quanto di più vicino a una ‘band’ si sia mai visto nella musica cosiddetta colta, aveva iniziato a sperimentare varie forme di improvvisazione più o meno controllata che ricadevano sotto l’etichetta di Musica Intuitiva.

Il massimo della musica intuitiva viene raggiunto nel 1968 con il ciclo Aus den sieben Tagen (dai 7 giorni: accenno evidente alla creazione). Le partiture dei 12 brani che lo compongono sono in realtà brevi testi di istruzioni sommarie che spesso richiedono all’esecutore anche un impegno meditativo non banale e a volte tale da portarlo anche vicino allo stato del Buddha («…arriva a uno stato di non pensiero…»).

Peraltro, alcuni dei brani sono decisamente belli, grazie evidentemente alla bravura degli esecutori e alla direzione di Stockhausen che partecipa alle esecuzioni.

Sul concetto di Musica Intuitiva Stockhausen afferma:

I call this music Intuitive Music, because with a text like the one for IT [citato sopra, in rosso; nota mia], one should exclude all the possible systems which are usually used for any kind of improvisation if one understands the term “improvisation” in the way it has always been used. I therefore prefer the term Intuitive Music. We shall see how Intuitive Music is going to develop in the future.

Question: Were there ever any performances which in your view were failures?

Stockhausen: Do you mean, in which we couldn’t play at all?

Question: No, in which something was played which to your musicians’ creative sense seemed to be rubbish? Or is there such a thing as rubbish?

Stockhausen: Absolutely. The first sign of rubbish is the emergence of clichés: when pre-formed material comes out; when it sounds like something which we already know. Then we feel that it is going wrong. There is a sort of automatic recording within us, which also automatically spits out all the recorded stuff also the garbage , and then one stops.

Question: Have you any way of eliminating acoustical rubbish from the creative process?

Stockhausen: Certainly. While playing Intuitive Music it becomes extremely obvious which musician has the most self-control; the musicians soon reveal whether they are critical, whether the physical and spiritual sides are in a certain balance etc. Some musicians are very easily confused, because they do not listen. That is the usual reason for rubbish rubbish in the sense that they produce dynamic levels which erode the rest for quite some time, without realising it themselves. In certain situations some become very totalitarian, for example, and that leads to really awful situations of ensemble playing. The sounds then become extremely aggressive and destructive; they operate on a very low level of communication, and destructive elements prevail (I hope we understand one another: I do not only mean simply “ugly” or “beautiful” when I say “low” level; I mean bodily, physically destroying each other). Then they all play at once. This is one of the most important criteria, that one must constantly remind oneself: “Do not play all the time”, and “Do not get carried away to act all the time”.

After several hundred years of having been forced to play only what was prescribed by the composers, once musicians now have the opportunity in Intuitive Music to play all the time, they do. The playing immediately becomes very loud, and the musicians do not know how to get soft again, because everybody wants to be heard. I mean, it is easy to get loud, but how can you get soft again? Finally you think: “Nobody hears me anyway, so I might as well stop”.

These are the general principles of group behaviour, of group playing.

From: Questions and answers on Intuitive Music, vedi anche Stockhausen – Questions and answers on Intuitive Music Pt 1 e Pt 2

Qui ascoltiamo due esecuzioni di Treffpunkt (punto di incontro) il cui testo base, che risale all’8/5/1968, è il seguente:

Everyone plays the same tone

Lead the tone wherever your thoughts

lead you

Do not leave it, stay with it

Always return

to the same place

Le due esecuzioni sono state registrate nello stesso giorno (27/8/1969).

Esecutori: Aloys Kontarsky (piano), Rolf Gehlhaar (tam-tam with microphone and bamboo flute), Carlos R. Alsina (piano), Michel Portal (tenor saxophone and clarinet), Vinko Globokar (trombone), Karlheinz Stockhausen (glissando flute, short-wave receiver, 1 filter and 2 potentiometers for tam-tam).

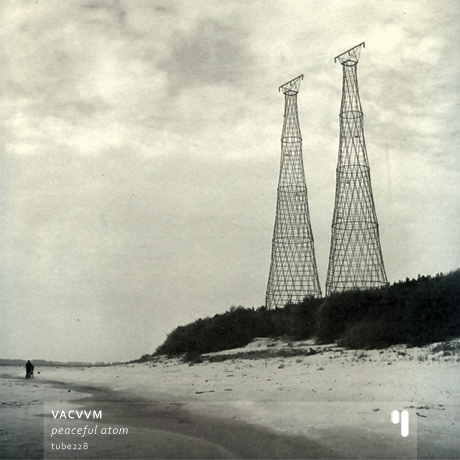

When it was born in the mind of italian musician Guglielmo Cherchi (aka VACVVM), ‘Peaceful Atom’ was intended to be a concept work about the Chernobyl disaster, and as a result of this some tracks are ideally connected to that topic: the title track (referring to the name of the first RBMK – Reactor Bolshoy Moshchnosty Kanalny – reactor), SCRAM (the emergency shutdown of a nuclear reactor), Lava Flow (the melted material erupted from the reactor after the explosion), Leaving Pripyat (the evacuation of the nearest city to the powerplant), Worm Wood Forest (the dead trees killed by the radiations) and Ignalina’s Sunset (Ignalina was the last nuclear powerplant to use a RBMK reactor, the same model involved in the Chernobyl disaster, which was only shut down in 2009).

When it was born in the mind of italian musician Guglielmo Cherchi (aka VACVVM), ‘Peaceful Atom’ was intended to be a concept work about the Chernobyl disaster, and as a result of this some tracks are ideally connected to that topic: the title track (referring to the name of the first RBMK – Reactor Bolshoy Moshchnosty Kanalny – reactor), SCRAM (the emergency shutdown of a nuclear reactor), Lava Flow (the melted material erupted from the reactor after the explosion), Leaving Pripyat (the evacuation of the nearest city to the powerplant), Worm Wood Forest (the dead trees killed by the radiations) and Ignalina’s Sunset (Ignalina was the last nuclear powerplant to use a RBMK reactor, the same model involved in the Chernobyl disaster, which was only shut down in 2009).

I rumeni Felix Petrescu (Waka X) e Valentin Toma (Qewza), nel 2001 hanno dato vita a questo progetto sperimentale chiamato Makunouchi Bento (che è il nome di un pranzo “al sacco” giapponese).

I rumeni Felix Petrescu (Waka X) e Valentin Toma (Qewza), nel 2001 hanno dato vita a questo progetto sperimentale chiamato Makunouchi Bento (che è il nome di un pranzo “al sacco” giapponese).